Seven years after the oil spill, some claimants are still waiting for the courts to recognise culpability, writes Feng Hao

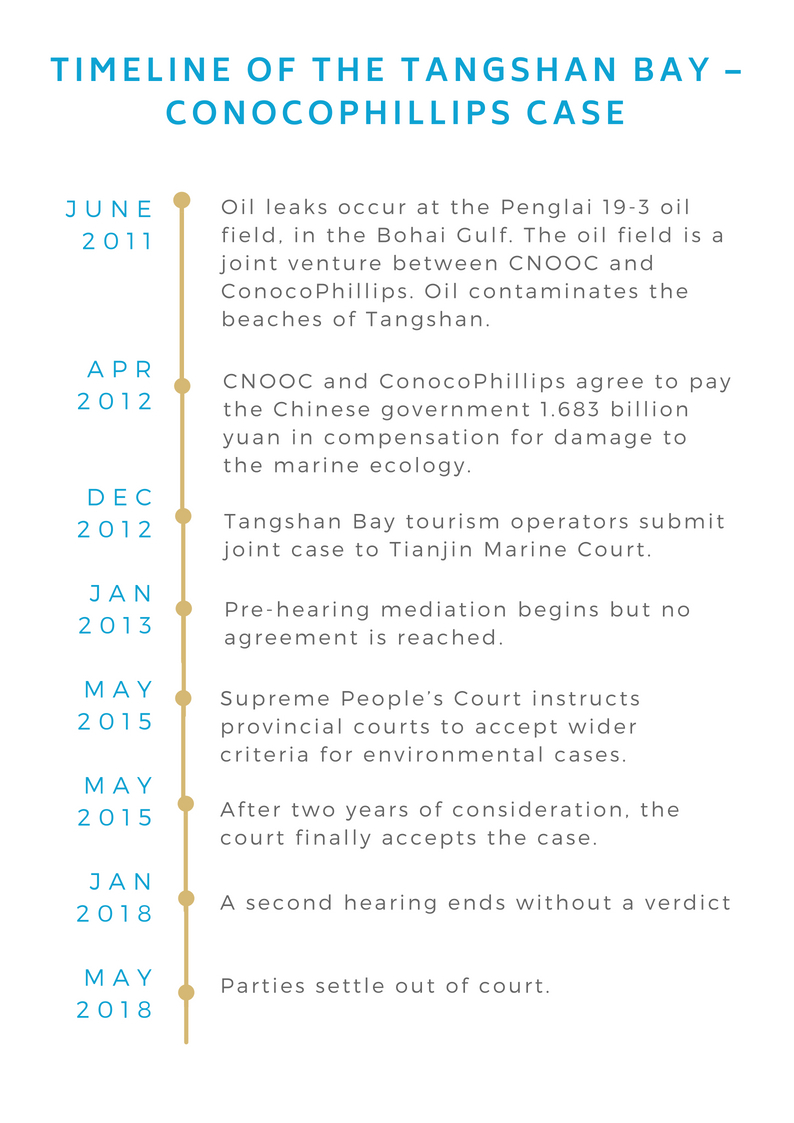

Along and hard-fought lawsuit brought by a group of Chinese tourist operators against United States oil giant ConocoPhillips has quietly ended with an out-of-court settlement behind closed doors.

Despite the absence of media attention on the ruling, to ignore it would be a mistake. The drawn-out litigation, which has lasted six years, holds important lessons for the development of China’s maritime law, particularly how to legislate the thorny of issue of accountability.

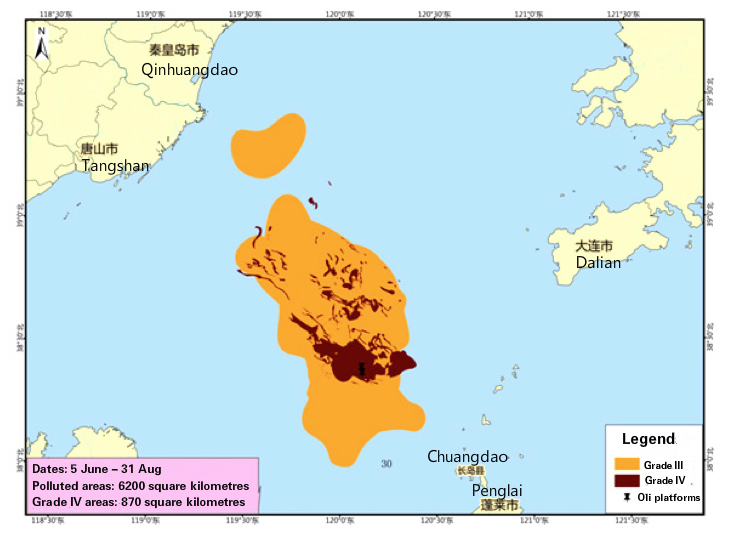

The tourist operators’ case started in November 2012 following the Bohai Bay oil leak in 2011, one of China’s most serious maritime spills. Between June 4 and 17, 2011, several major oil leaks occurred in the Bohai Sea from offshore oilfields only 80 kilometres from the nearest city on China’s east coast. The drilling companies, the China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC) and ConocoPhillips China, reacted slowly and the leak spread, polluting 6,200 square kilometres of water – an area six times the size of Singapore – around the main oil field, Penglai 19-3.

The leak was China’s worst coastal environmental disaster for years. The petrochemical pollution stretched 200 kilometres north-west to the island of Yuetuo, a scenic area known commercially as Tangshan Bay International Tourism Island, home to the tourist companies that brought the case.

Economic disaster

One month after the incident, a report by the former State Oceanic Administration (SOA) showed that a 500-metre oil slick still coated the beaches of Tangshan. In April 2012, a final agreement was reached between the SOA, CNOOC and ConocoPhillips to pay 1.683 billion yuan into a compensation fund.

The agreement provided compensation for aquaculture and fishing sectors in certain parts of Hebei and Liaoning provinces. However, Shandong and Tianjin received nothing. Nor was there any provision for the tourism sector.

There is no public information available detailing if and how the money was distributed by the local provincial authorities.

Having been left out of the compensation deal, and with livelihoods damaged, the Tangshan tourism operators bandied together to seek reparation.

A long wait for justice

In August 2012 the tourism operators, including some from Yuetuo, submitted an application for mediation to the SOA, which is formerly responsible for managing compensation for marine oil leaks, with the hope of obtaining compensation from ConocoPhillips.

This was the first time in China that companies united to seek compensation in the wake of an oil spill.

The operators claimed that the leak had caused business losses amounting to 26.2 million yuan (US$4 million) due to a decline in visitor numbers.

Initially the SOA rejected the request on the basis that the companies were ineligible, the claimants’ lawyer Huo Zhijian told chinadialogue. But they persevered and took the case to a senior Tianjin Marine Court, where it was formally accepted in May 2015. It would be another three years before any agreement was reached.

How to assess oil leak losses?

How to assess oil leak losses?

One challenge for the claimants was establishing a direct link between the pollution and the losses suffered. Under Chinese law, the claimant is responsible for providing evidence of the link between the pollution and any resultant losses.

“Legally, the hardest thing to prove is the cause-and-effect relationship,” said lawyer Zhao Jingwei, who successfully represented a number Bohai aquaculture operators.

The International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds hold that while not directly due to an oil leak, such losses are a foreseeable result of one and so can be regarded as arising from the leak. But in practice Chinese courts tend to reject such claims.

While direct losses from tourism may be more difficult to determine compared to fishing, for example, where the loss of fish stocks is easier to prove, it is likely that a major pollution incident would deter tourists travelling to places formerly known for their natural beauty.

The slow arm of the law

All known compensation cases brought as a result of the Bohai oil leak have been protracted and problematic. A case brought by Tianjin fishermen was rejected by the government courts, and 500 Shandong fishermen are still waiting for their case to be heard. This reflects the weakness of the Chinese legal system in dealing with oil pollution accidents in the marine environment.

This reflects the weakness of the Chinese legal system in dealing with oil pollution accidents in the marine environment

After the 2010 Deepwater Horizon leak in the Gulf of Mexico the US stepped up regulation of marine energy development. The Penglai 19-3 leak was an opportunity for China to revise and improve the Marine Environmental Protection Law.

In 2012 China’s legislative body, the National People’s Congress, indicated on its website that in response to the Bohai oil leak the Congress and the State Council would work on revising that law together with the Ministry of Environmental Protection, Ministry of Agriculture and the State Ocean Administration.

The Marine Environmental Protection Law has since gone through two revisions, in 2013 and 2016, with new content added on coastal engineering and environmental pollution.

The 2013 revision ruled that an environmental impact assessment must be submitted during feasibility studies for coastal engineering projects, and that oil prospectors must submit emergency plans in the event of oil leaks.

In 2016 more detailed methods for calculating compensation for pollution were added, as were fines for major pollution incidents.

Local governments have also sent encouraging signals. In 2016 the Shandong government published rules for managing marine compensation – the first such document in China.

The principle of that method means that victims of pollution can claim damages through harm to a regional ecosystem, without having to prove a cause-and-effect link. This is regarded as a step forward in the development of a marine ecological civilisation.

However, governance issues continue to impede justice. Losses to marine wildlife, for example, are under the remit of the fisheries authorities and whereas mineral resources fall under the mining authorities. This split approach to governance makes it’s hard to identify where to attribute losses.

Feng Jie, a journalist who reported in depth on the Penglai 19-3 leak, says that current structures are failing to guarantee justice for victims of pollution.

Whilst the enormous environmental costs of the Bohai leak have spurred improvements to China’s marine environmental protection law, legislators still have much to do.

Đăng nhận xét