By Susan D’Agostino | February 4, 2022

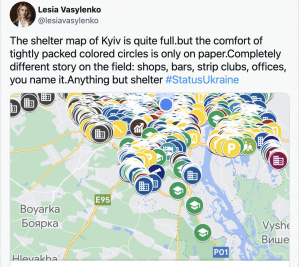

Ukraine’s populous capital, Kyiv, is only a few hours’ drive from the border where Russia has been amassing troops in ever-greater numbers. In the event that Russia invades, Kyiv residents may need shelter. Toward this end, Ukrainian authorities have published an online, interactive map identifying more than 5,000 potential bomb shelter sites that could accommodate more than 2 million people. But not everyone is convinced that shelter will be necessary. And even some who see a potential need question whether the shelters will be accessible in the event of war.

“Here in Ukraine, people got used to this everlasting security threat coming from Russia for years,” Illia Ponomarenko, a journalist in Kyiv, said of the city’s packed cafes and restaurants. “Ukraine lives on in what we call ‘reasonable carelessness.’” As global news headlines reach a fevered pitch and social media boils over about Russia’s military buildup on the border, Kyiv’s residents exude a business-as-usual vibe.

“Either nobody here’s expecting war to break out any minute now, or they’re just not very well prepared for it,” Olivia Lace-Evans, a BBC journalist, said upon visiting one of the bomb shelter sites on the city-issued map. She stopped by the shelter—a clothing store—in daylight hours but found it closed and locked.

In peacetime, many of the shelter sites, which include schools, shops, metro stations, and underground passages, serve civilian purposes. In the event of an emergency, including one of “military nature,” owners of the listed shelters are required to provide free access to their facilities, according to the Kyiv City Council website.

Yet a shopkeeper at another bomb shelter listed on the map—a stationery store—was unaware that the facility had been designated for the purpose, according to Lace-Evans. The store’s manager later told her that the shelter was nearby but had been boarded up for about 14 years.

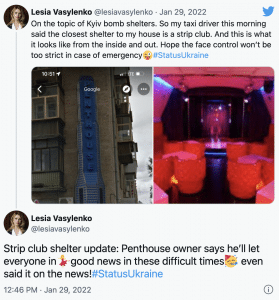

“The shelter map is quite full. But the comfort of tightly packed colored circles is only on paper,” Lesia Vasylenko, a member of Ukraine’s Parliament, tweeted. She later shared her concern that the closest shelter to her house was a strip club. A day later, she provided an update: “Penthouse owner says he’ll let everyone in [dancer emoji] good news in these difficult times [face emoji with party hat, noise maker and confetti] even said it on the news!”

Other government workers are more sober when referring to a potential need for shelter.

“The key bomb shelter in the city of Kyiv will also be the Kyiv subway, which, in the event of—God forbid—zero hour, will be ready to accommodate people who can take shelter in case of a possible attack,” Mayor Vitali Klitschko said in an interview with the Current Time television network. The Arsenalna Metro Station in Kyiv is the deepest metro station in the world with what some dub a “never-ending escalator ride.” (In truth, the ride takes approximately five minutes, and the station has stairs as well.)

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken has urged US citizens to “strongly consider leaving” Kyiv. The Ukrainian government, in response, called that recommendation “premature” and an “excessive display of caution.”

As with planning for natural disasters, the Kyiv City Council posts notification procedures and shelter options for potential military emergencies on its website. Sirens would alert residents, followed by a voice message transmitted over a broadcast network, radio, and television, and by way of cars equipped with speakers. A potential message would encourage residents to “act without panic and fuss in accordance with the instructions.” The alert would include information about the emergency, affected areas, and a recommended course of action, which may include seeking shelter.

Yet on a recent walk around Kyiv, Ponomarenko discovered that many of the shelters were not fit for service based on official guidelines. Some of the shelters hail from the Soviet era, with ventilation systems that must be “cranked to life [by hand] like an old car.”

Iryna Lada, a Kyiv resident, has had a “go-bag”—a carryall with important paperwork, health essentials, and basic necessities—packed since 2014, according to the Swiss Radio and Television Society. Indeed, though international headlines have recently spotlighted a potential Russian threat, Ukrainians have been living with the threat for some time.

“Putin’s attachment to Ukraine is toxic,” Anna Myroniuk wrote in The Kyiv Independent. “Putin is like that abusive ex-boyfriend that stays fixated on you after being dumped. You tell him to leave you alone, but he still follows you.”

Ponomarenko describes life in Ukraine as “hyperactive all the time, regarding anything.” His life as a Kyivan has not changed during this recent crisis. On the streets of Kyiv and other cities, he said, “Nothing [looks] weird. People go on living their lives, minding their own business.”

As the coronavirus crisis shows, we need science now more than ever.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent, nonprofit media organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Susan D’Agostino is an associate editor at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Her writing has been published in The Atlantic, Quanta Magazine, Scientific American, The Washington Post, BBC Science Focus, Wired, Nature, Financial Times, Undark Magazine, Discover, Slate, The Chronicle of Higher Education, and others.

Susan is the author and illustrator of How To Free Your Inner Mathematician: Notes on Mathematics and Life (Oxford University Press, 2020). She is a member of the editorial board of the Mathematical Association of America’s Math Horizons magazine.

Susan earned a PhD in mathematics at Dartmouth College and an MA in science writing at Johns Hopkins University. She has received science writing fellowships from the National Association of Science Writers, the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing, and the Heidelberg Laureate Forum Foundation.

(Sources: Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists)

Đăng nhận xét