For years, city planners have prioritised cars, but they're now taking a different route, writes Liu Shaokun

Encouraging bicycles and investing in public transport are just some of the ways Chinese cities are trying to minimise car use (Image: chuyu)

Plagued by congestion and pollution, China’s cities are exploring models of transportation that are more sustainable in terms of their social, environmental and climate impacts. Some have emerged as global leaders, such as Hangzhou, south-west of Shanghai, which in 2017 won an international award for its municipal bike sharing scheme. More recently Shenzhen, a major city north of Hong Kong, electrified its entire fleet of public buses, gaining worldwide recognition.

Over the past 40 years China has undergone rapid urbanisation. In the 1980s, the one-time “kingdom of the bicycle” saw economic reforms and the transition to motorised transportation. The country is now shifting again, this time towards modern, sustainable transportation. Today, you can use your mobile phone to unlock a shared bike, ride it along a dedicated cycle path to the nearest Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) station, park the bike and ride on to your next destination. Such journeys are already an everyday occurrence in many Chinese cities.

As the world’s largest developing nation, China’s experience of large-scale experiments with transport and implementation are of huge value to other developing countries.

Urban rail and bus rapid transit: A response to rapid motorisation

China started large-scale construction of urban rail and bus rapid transit options in 2004. By the third quarter of 2017, 29 Chinese cities had some form of urban rail (defined as subways, light-rail, monorail and automated people movers, or APMs), with 118 lines stretching a total of 3,862 kilometres and carrying 17.68 billion passengers per year.

Urban rail systems in Shanghai and Beijing are longer than London’s and busier than those of New York and Paris. Urban rail in some Chinese cities accounts for about half of all public transport journeys.

But rail transit is expensive. The World Bank recommends developing nations adopt the medium-capacity and bus-based BRT model – an approach also welcomed by China’s city bosses. The design of Beijing’s BRT system, launched in 2005, drew on the experiences of Latin American countries such as Brazil’s dedicated “corridors”, separate lanes specifically for BRT buses; enclosed stations; fast and frequent services; off-board fare collection; and good information for passengers. As of early 2018, 32 Chinese cities have BRT systems, with over ten more cities planning, designing or building them. The BRT system in Curitiba, southern Brazil, was a major influence on the early designs of China’s own BRT systems.

In the early days, China’s application of Latin American BRT systems experienced some problems around integration with existing bus routes, and designs had to be adjusted to make them more appropriate for the specific structural needs of Chinese cities. China had a larger number of existing bus routes running along BRT corridors, meaning the impacts of the new lanes was limited. Whereas in Curitiba, the dedicated system only allowed a small number of routes to run along the corridor.

In 2009, Guangzhou province implemented a “dedicated corridor and flexible routes” model, allowing non-BRT buses to use the corridor, and BRT routes to operate outside it, which improved travel times.

Guangzhou’s BRT system also has a transport corridor, which fully combines different forms of transport. The corridor can handle 28,000 passengers per hour in peak direction – more than most subways and more than any light rail system worldwide. In 2011 the Guangzhou BRT system won the Sustainable Transport Award and the UN Lighthouse Award.

A BRT station in Jiangsu province, China. (Image: Conny Hetting 2012)

A BRT station in Jiangsu province, China. (Image: Conny Hetting 2012)

A people-centred street revolution

In response to the damage done by motorised transport to urban mobility, air quality and health, Chinese cities have started remoulding urban spaces. When it comes to design, there is a greater focus on how people interact and live.

Over the past 40 years China has undergone rapid urbanisation. In the 1980s, the one-time “kingdom of the bicycle” saw economic reforms and the transition to motorised transportation. The country is now shifting again, this time towards modern, sustainable transportation. Today, you can use your mobile phone to unlock a shared bike, ride it along a dedicated cycle path to the nearest Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) station, park the bike and ride on to your next destination. Such journeys are already an everyday occurrence in many Chinese cities.

As the world’s largest developing nation, China’s experience of large-scale experiments with transport and implementation are of huge value to other developing countries.

Urban rail and bus rapid transit: A response to rapid motorisation

China started large-scale construction of urban rail and bus rapid transit options in 2004. By the third quarter of 2017, 29 Chinese cities had some form of urban rail (defined as subways, light-rail, monorail and automated people movers, or APMs), with 118 lines stretching a total of 3,862 kilometres and carrying 17.68 billion passengers per year.

Urban rail systems in Shanghai and Beijing are longer than London’s and busier than those of New York and Paris. Urban rail in some Chinese cities accounts for about half of all public transport journeys.

But rail transit is expensive. The World Bank recommends developing nations adopt the medium-capacity and bus-based BRT model – an approach also welcomed by China’s city bosses. The design of Beijing’s BRT system, launched in 2005, drew on the experiences of Latin American countries such as Brazil’s dedicated “corridors”, separate lanes specifically for BRT buses; enclosed stations; fast and frequent services; off-board fare collection; and good information for passengers. As of early 2018, 32 Chinese cities have BRT systems, with over ten more cities planning, designing or building them. The BRT system in Curitiba, southern Brazil, was a major influence on the early designs of China’s own BRT systems.

In the early days, China’s application of Latin American BRT systems experienced some problems around integration with existing bus routes, and designs had to be adjusted to make them more appropriate for the specific structural needs of Chinese cities. China had a larger number of existing bus routes running along BRT corridors, meaning the impacts of the new lanes was limited. Whereas in Curitiba, the dedicated system only allowed a small number of routes to run along the corridor.

In 2009, Guangzhou province implemented a “dedicated corridor and flexible routes” model, allowing non-BRT buses to use the corridor, and BRT routes to operate outside it, which improved travel times.

Guangzhou’s BRT system also has a transport corridor, which fully combines different forms of transport. The corridor can handle 28,000 passengers per hour in peak direction – more than most subways and more than any light rail system worldwide. In 2011 the Guangzhou BRT system won the Sustainable Transport Award and the UN Lighthouse Award.

A BRT station in Jiangsu province, China. (Image: Conny Hetting 2012)

A BRT station in Jiangsu province, China. (Image: Conny Hetting 2012)A people-centred street revolution

In response to the damage done by motorised transport to urban mobility, air quality and health, Chinese cities have started remoulding urban spaces. When it comes to design, there is a greater focus on how people interact and live.

When it comes to design, there is a greater focus on how people interact and live .

In 2016, Shanghai published the seminal Shanghai Street Design Guide, which signalled a shift in core urban design values away from cars and towards people. The guide emphasised walking and cycling – a previously overlooked consideration – and a reduction of space for vehicles. This aimed to prioritise slower forms of transport, providing space for pedestrians and ensuring the free flow of bicycles, in order to create a more pleasant and convenient environment.

Alongside Shanghai and Guangzhou, dozens of other cities including Wuhan and Nanjing, began working on their own guides to urban street design. More and more cities are joining the revolution.

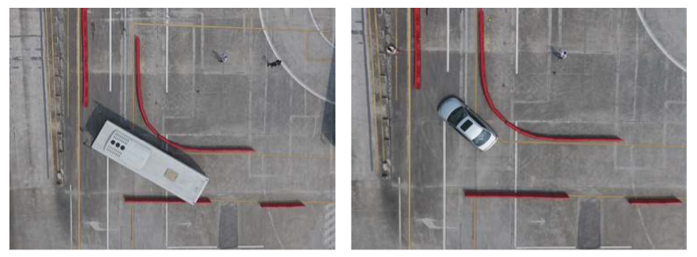

The Guangzhou Comprehensive Street Design Handbook tested turns of 4m, 5m, 8m, 10m and 12m radius with cars, 9-metre buses and 12-metre buses (Image: Guangzhou City Planning Design and Research Institute)

Embracing innovation: the electric bicycle and shared bike schemes

As China continues to urbanise, commuters need new forms of transport. Electric bicycles and the more recent shared bike schemes, pioneered by brands including Ofo and Mobike, have swept the nation. They have met the public need for both speed and convenience. But the influx of bikes has also been blamed for clogging up pavements and roadsides and causing a public nuisance.

By 2014, China had over 200 million electric bicycles, which represented the main form of transport for countless households. As of May 2015, over 10 million bikes had been placed around Chinese cities as part of shared bike schemes, with over 100 million registered users making over one billion trips. This has saved large amounts of carbon emissions, private companies and governments claim.

Electric bicycles do not directly produce any pollutants, they take up little space on roads and are suitable for short and medium-length journeys. They are faster than conventional bicycles, less tiring to ride, and reasonably cheap. The ability to rent and park shared bikes with few restrictions has encouraged their use in cities. The electric bicycle is an excellent option in cities with underdeveloped public transport systems, while shared bikes can help cover the “last mile” problem – the last leg of a journey, between a transport hub or connecting stop, and home – in instances where public transport is insufficient, replacing short-distance car journeys.

Data from bike-sharing firm Mobike shows that 81% of Beijing’s shared bikes are used around public transportation stops. The figure rises to 90% in Shanghai.

A first-quarter 2017 transportation report from mapping firm AutoNavi found the number of car journeys of five kilometres or less falling since shared bikes became available. Both Shanghai and Beijing saw drops of 5%.

Chinese cities have had to adapt quickly to the boom in shared bikes, including careless parking and dumping (Image: Slices of Light)

But these rapidly developing forms of transport present city planners with challenges. Electric bikes are relatively fast and their numbers are rapidly increasing but they have become a major cause of traffic accidents. Between 2013 and 2017 there were 56,200 accidents caused by electric bicycles resulting in death or injury in China, with 8,431 people killed and 63,500 injured. The biggest issue with shared bikes, meanwhile, is inconsiderate parking, the underlying cause of which is a lack of infrastructure and a long-standing failure to legislate for bicycle use.

So these new forms of transport often come into conflict with city managers. However, the government is gaining valuable experience as it attempts to design policies for their use. For example, China initially limited the speed and weight of electric bicycles, a controversial move with the public. Some local governments simply banned or limited their use.

These attempts eventually led to the “Nanning model”, named after the city in the southern Guangxi province near the border with Vietnam, which abandoned outright bans in favour of optimising traffic signals, improving signage and road safety education. This enabled the city and the electric bicycle to co-exist.

Similarly, the central government has issued regulations to guide the rapid uptake of shared bike schemes in an effort to steer, rather than stop, their growth. Some cities have also started to improve and expand infrastructure such as bike lanes to boost “bike-friendliness.”

Lessons from China’s experience

As a large developing nation, China can provide valuable lessons for other countries at a similar stage of development on the opportunities and challenges of shifting to sustainable transport in their cities:

Good quality public transportation is the foundation of sustainable mobility

For low carbon transport to grow, public transport must compete with cars, which means it needs to be quick, convenient and comfortable. Good quality public transport doesn’t just mean more services. It is more important that it is well-designed and operated in order to provide quality services to more people. This has been a key precept for some Chinese cities in curbing the growth of car use and rapidly shifting towards sustainable transportation.

High-capacity public transport (subways, trams and BRT) in São Paulo, Brazil, reaches 25% of the city’s population. In Beijing, the figure is 60%, which has allowed it to successfully replace some forms of private transport.

Developing an integrated multi-modal transportation system is vital

Fully integrating cycling with public transport promotes the inclusive and coordinated development of public transport. It’s more attractive to the public and solves the “last mile” problem.

Build person-centred cities

After falling into the trap of turning streets into huge spaces designed for cars, Chinese cities are starting to realise that cities should be built to provide pleasant environments for people to live in. This has given rise to a concerted shift towards person-centred urban design.

The experience of Chinese cities also shows that if a selection of sustainable public transport options is provided, residents will leave their cars at home. In Nanning, 45% of electric bicycle riders live in a car-owning household.

Embrace transportation innovation

As science and technology have advanced, new forms of transportation and modes of travel have appeared in China, such as electric bikes with long-life batteries and shared pubic bike schemes that rely on “fintech” (financial technology) payment systems. This transition has not been smooth but, ultimately, innovation has spurred the shift toward sustainable transportation.

An earlier version of this article appeared in Diálogo Chino

Now more than ever…

chinadialogue is at the heart of the battle for truth on climate change and its challenges at this critical time.

Our readers are valued by us and now, for the first time, we are asking for your support to help maintain the rigorous, honest reporting and analysis on climate change that you value in a 'post-truth' era.

Đăng nhận xét