Bill McKibben | Sep 16, 2019

Thirty years ago this month, I published my first book, The End of Nature, which was also the first book for a general audience about what we then called the greenhouse effect. And my main worry was about … nature.

In 1989, global warming was still a theoretical crisis—we were right at the edge of being able to measure it, and even the great NASA scientist James Hansen, who first brought the crisis to our country’s attention, stressed it would take another decade before the “man in the street” would begin to feel it. So, in those early days, it made sense to focus on what climate change was doing to our idea of the world, the way it was transforming our sense of the wild. I lived in the Adirondacks, in the great eastern wilderness, and I knew that the meaning of this remarkable place was beginning to shift. Suddenly no place, no matter how remote, was apart from man, and that was philosophically sad—the federal Wilderness Act of 1964 delineates those places where “the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” It was clear there would no longer be such places.

As time went on, however, something else became clear, too: that there were deeper and more pressing reasons to fight climate change.

I remember a reporting trip to Bangladesh almost two decades ago. I saw the rising seas and the rivers fed by the fast-melting glaciers of the Himalaya. But mostly, I saw people dying in the country’s first big outbreak of dengue fever, a disease spread by mosquitoes expanding their range on an ever-warmer, ever-wetter planet. Since I was spending a lot of time in the slums, eventually I got bit by the wrong mosquito myself, and I was as sick as I have ever been—but I was more fortunate. I was strong and healthy going in, so I did not perish. Plenty of Dhakans did die—and as I watched it happen, I began to obsess over the fact that they had done nothing to cause the trauma they were experiencing. Carbon emissions from Bangladesh were barely a rounding error in the global tables.

Arrestable. By 2013, the author had transformed from “mostly a writer” to Chief No-KXL and found himself cuffed in front of the White House while protesting the Keystone Pipeline. He kept fancy company in jail that day, however, including Sierra Club Executive Director Michael Brune and social justice activist Julian Bond. Photo: Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Arrestable. By 2013, the author had transformed from “mostly a writer” to Chief No-KXL and found himself cuffed in front of the White House while protesting the Keystone Pipeline. He kept fancy company in jail that day, however, including Sierra Club Executive Director Michael Brune and social justice activist Julian Bond. Photo: Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post via Getty Images

When I came home from the trip, I began an evolution from “mostly a writer” to “mostly an activist.” I started to organize groups like 350.org and I began winding up in jail. And it has been a great pleasure to watch the climate movement, as it has grown, focus its attention ever less on the natural world and ever more on the injustice that is at the core of this strange moment in history.

Some of that injustice is racial and colonial: The iron law of climate change is, the less you did to cause it, the sooner you feel its effects. Some of that injustice is intergenerational: Those who poured the most carbon into the air will be dead before its effects are fully felt. That’s why the leadership of this movement looks the way it does: people from frontline communities, Indigenous people and young people.

Very young people. The great climate strike that will take place around the world this Friday has its roots in the efforts of junior high and high school students, with more than a few elementary school students thrown in. I’ve gotten to know many of them—not just Greta Thunberg, but also the young people on every continent who are carrying out the same noble work. They are deeply aware, in a truly hopeful way, of the connections between people around the planet. They understand the stakes. They’re adept at working together.

And thank heavens for that—it means they’ll be less prone to the dark sides of environmentalism, less likely to succumb to the idea that what matters most are our particular places or that it might make sense to set up walls to protect those places and keep others out. You can find that kind of regressive, nationalistic streak in some kinds of nature worship, right back to fascist Germany. But you can’t find it, I don’t think, in what we know about the science of climate.

Because that science makes it utterly clear that everything is connected. We have one climate system; carbon emitted in one place warms every place. As the climate heats, the effects are felt everywhere. Even Houston, ground zero for the oil industry, which had the greatest rainstorm in American history when Hurricane Harvey blew in.

Home is where the heart is, and Hurricane Dorian was another heartbreaker. Though it’s misleading to say climate change causes more hurricanes, there’s a rough consensus that it is making these storms heavier and more lethal. Photo: Leila Macor/AFP/Getty Images

Home is where the heart is, and Hurricane Dorian was another heartbreaker. Though it’s misleading to say climate change causes more hurricanes, there’s a rough consensus that it is making these storms heavier and more lethal. Photo: Leila Macor/AFP/Getty Images

The poorest people in Houston suffered the most, of course—that’s what usually happens. And that’s why it is so important that the climate movement focuses, above all, on solidarity. That’s what the Green New Deal offers: an opportunity to involve everyone in this fight for our common future. That’s what the climate strikes are: a reminder that young and old on every continent are now called to an intrinsically global fight. And that’s why, increasingly, the climate fight is melding with the efforts for humane immigration policy: When people have to leave their Guatemalan farms because of an unending drought they did not cause, the answer can’t be cages and walls. That’s why I found myself in jail last month in those same Adirondacks, where I’d once worried mostly about nature. This time, we were protesting the injustice of our country’s immigration policies: As climate change puts people around the world on the move, all we have to offer is walls and cages. That’s not OK; climate policy is immigration policy is poverty policy. Climate isn’t an issue—it’s a lens, a way to understand the economy, politics and foreign affairs. If growth was how we understood the 20th century, survival is how we’ll bottom line the 21st.

Nature still matters, of course. The staggering injustice of climate change cuts across creation, too, as the recklessness of one small fraction of one species starts to trigger a mass-extinction event that will take out a huge part of the planet’s DNA. One is right to be both mad and sad about that. The polar bear may not be the best symbol for the climate crisis (a dubious honor reserved, perhaps, for the inhabitants of some low-lying Pacific island), but that doesn’t mean polar bears don’t count. Everything and everyone counts. Only by holding fast to each other do we stand a chance of making it through this most dangerous of centuries.

Author Profile

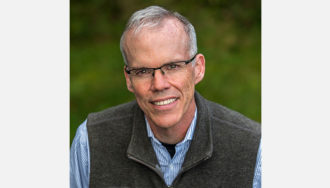

Bill McKibben

Bill McKibben is the author of Falter, the latest of several books, and a founder of 350.org, the grassroots climate change movement. A long-time friend to several of us at Patagonia, we don’t see him nearly enough because he lives in the mountains near Lake Champlain. In 2014, a few biologists saw fit to name a new species of woodland gnat — Megophthalmidia mckibbeni — in his honor.

Đăng nhận xét