Congestion, rising housing prices, rising cost of living and increased homelessness are all stressors—but so-called social compacts can help

Credit: Getty Images

A recent report from the Economist Intelligence Unit highlights the increasing fragility that urbanization can bring. Jakarta’s rising urban population is facing challenges due to its unique water infrastructure. Flooding and continued pollution from deep water pumps have caused billions of US dollars in damages and considerable loss of life, especially among lower socio-economic families in flood prone areas. Furthermore, a rise in the population of Bangkok (now the ninth largest population in east Asia) has seen the city’s traffic congestion rating rise from 30th to 12th globally in just two years, resulting in the average driver experiencing roughly 64 hours of traffic congestion each year.

Globalization has accelerated the rate of industrialization within east Asian countries and while it has brought economic and social opportunities to these countries, it has also had numerous unintended consequences associate. Alongside the rise of globalization has been an increase in urbanization; 55 percent of the world’s population now live in urban areas. A recent World Bank Report discusses 200 million people moving to urban areas in East Asia alone, equivocal to that of sixth largest population for any single country.

Consequently, the bulk of the economic boons of globalization are being captured by cities. Currently, Tokyo contributes 1.6 trillion dollars to Japan’s GDP (almost double the entire nation of Malaysia). Cities are becoming increasingly more complex due to the dual forces of globalization and urbanization, which makes city governance harder, thus social compacts are more likely to go unfulfilled. An example of this is the consistent trend for governments to prioritize continued economic development over sustainable living practices for citizens. In other words, cities are becoming increasingly fragile.

Fragility occurs when there is some break down in how society ought to work. Increased congestion, rising housing prices, rising cost of living, and increased levels of homelessness are all examples of urbanizations increasing fragility. Urbanization and globalization are creating fragility in cities faster than the traditional model of reactive governance, addressing issues as they occur, can address.

We encourage policy makers to think about urban fragility along the same vein as resilience, in fact fragile cities tend to be more damaged by natural disasters than relatively un-fragile cities. By understanding urban fragility, we instead argue for a framework of considering issues in terms of failed social compacts, which should allow policy makers to take a more proactive and holistic approach to addressing fragility.

Social Compacts

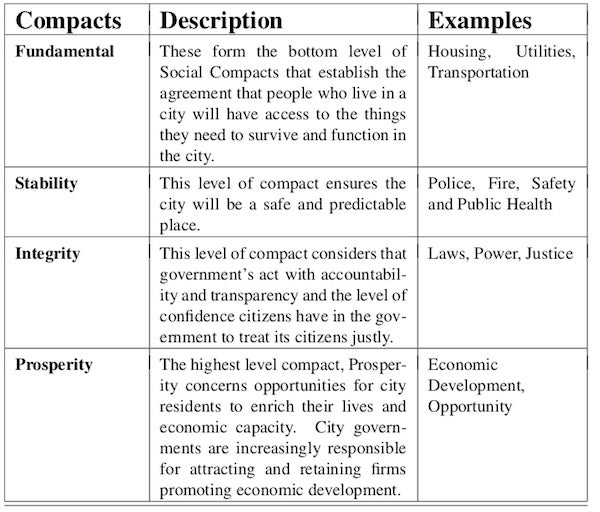

Social Compacts are the norms, traditions, and laws that bind society together, through both implied and explicit agreements between government and individuals (e.g., cultural norms). They determine which problems governments should address, and what are acceptable solutions to those problems.

Since cities do not have unlimited resources, they cannot address all compacts. This means that cities will always have some form of fragility, and that compacts have to be prioritized in order to minimize the fragility a city faces.

Therefore, compacts need to be categorized according to a hierarchy of social compacts. Broadly speaking, there are four levels of compacts: fundamental, stability, integrity and prosperity. Starting with fundamental, cities need to prioritize fulfilling these compacts.

Globalization within the Asia region

Countries of the Asian region have experienced a tremendous amount of economic growth and development. Economies such as Singapore, Hong Kong and South Korea have all utilized nationwide industrialization and neo-liberal approaches to economic policy in order to provide attractive centers for foreign investment.

In doing so, each country has seen remarkable progress in a short amount of time, with South Korea placing in the top 10 exporters globally, Singapore experiencing double digit annual growth of GDP during the 1970’s, and Hong Kong property values increasing by 8 percent per annum for the previous 25 years.

Unfortunately, economic growth associated with globalization has corresponded with a rise in the complexity of governing urban areas. Generally, city governments tend to prioritize the prosperity compact over the concerns of citizens. A top down approach is adopted across the social compact framework, wherein prosperity is focused, integrity is required to uphold the prosperity, and fundamental compacts are merely reacted to as issues arise.

The following east-Asian examples demonstrate issues that have arisen from prioritizing prosperity to the exclusion of other compacts. We suggest that with the correct application of the social compact framework, governments can design better policy to proactively mitigate these problems.

Singapore

Singapore’s rapid economic development during the previous 50 years of independence has been recognized globally as a highly successful means of city and state governance. Early on, the government spearheaded a focus on education and industrialization supported by social policy built on meritocratic and neo-liberal values.

Perhaps the most successful and well recognized of these policies, is their Public Housing Scheme. This particular scheme is responsible for providing 90 percent of Singapore’s population with home ownership, and is such a successful method that during the 1990’s the United Nations would invite other countries to study the policy.

By providing citizens with a scheme that meets their fundamental compact (housing), citizens are better situated to support the prosperity compacts allowing for more sustainable economic growth. A differentiator from other Asian regions, this public housing scheme plays a largely supportive role in Singapore’s ability to develop economically. The government’s control of housing allows Singapore to regulate and control the housing market to ensure it aligns with the merit-based social values they promote.

Singapore’s housing policy was initially successful because it promoted fundamental compacts along-side integrity compacts. The government tied membership of the Public Housing Scheme with conformity to social values. The policy started causing fragility when globalization brought diversification that did not align with traditional social values such as housing for single parents.

The government of Singapore has been slow to respond to this shift because they believed adhering to social values (integrity compact) was responsible for the economic success of the city, instead of the meeting all resident’s fundamental compacts.

This failure to understand the social compact framework has resulted in a rise in homelessness and an increased stress on the interim and public housing scheme programs. These previously successful programs have increased 400 percent in their application processing times, leaving applicants potentially homeless for up to two years.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong utilizes both public housing, and government leased housing policies to develop itself economically and attempt to regulate the housing market. Over the previous 40 years, the Hong Kong Housing Authority (HKHA) has built over 660’000 rental flats, and is considered one of the largest public housing bodies in the world. Initially, Hong Kong introduced the Home Ownership Scheme as a way to provide low-income households with an opportunity to afford home ownership. Whilst extremely beneficial to Hong Kong’s lower income citizens, this scheme also provided massive economic benefits as it allowed the government to relocate labor to aid in industrialization. Between public housing and government owned property, Hong Kong policy was able to link a critical mass of people with industry, which consequently improved both the business and public environments.

However, post the Asian financial crisis, Hong Kong has struggled to offer as consistent of a policy as Singapore. During 2002, the government renounced the development of any Home Ownership Scheme flats and in 2004, the government began selling Home Ownership Scheme projects to private developers. The sale of the scheme’s development plans to private enterprise counters the exact purpose of the scheme’s initial implementation – to provide subsidized housing to those who could not afford to enter the private market. In the following years, as low-income households were left with unfulfilled fundamental compacts, the private real estate market prices surged over 275 percent.

Currently, the Hong Kong government is only responsible for roughly 40 percent of the housing market, which is largely limiting on their ability to align housing policy with economic development.

The Hong Kong government’s decision to prioritize economic prosperity over fundamental housing has resulted in a reactive policy cycle where continued economic development is no longer led by the industrialization and mobilization of a workforce, and instead is decided by private developers purchasing power.

The property market inflation in Hong Kong provides a perfect example of the increasing fragility that urbanization can bring to cities. Almost a decade since the Home Ownership Scheme has been re-implemented, homelessness figures are still increasing roughly 20 percent per annum with a record 1.37 million citizens living below the poverty line. These figures are yet to include the numerous other citizens who utilize 24-hour McDonalds and internet cafés for shelter, of which are estimated at increasing roughly 50 percent in the previous 12 months. It is crucial that governments consider the fundamental level of social compacts before aligning themselves with economic development.

Seoul

Seoul largely focuses on continuous urban renewal as a way to attract both foreign tourism and investment and has previously found economic success using this method, utilizing urban transformation as a way to attract foreign investment and compete globally.

Similar to the previous examples, Seoul’s economic development is largely due to its ability to meet the rising needs of globalization and benefit from industrialization. However, the city goes one step further in utilizing urban transformation as a way to physically promote an innovative image, advertising its transformation of fundamental compacts as a means to attract tourism and foreign investment. The Cheonggyecheon restoration project was initially globally successful as an attractive solution to rising urbanization issues, providing further economic interest from business and tourists.

Unfortunately, aligning urban transformation with economic goals and a global outlook has prioritized the attractiveness of foreign investment over the fundamental quality of life provided to all citizens. Specifically, whilst foreign investment can have positive effects on economic growth, it can also outsource the conversation of urban transformation to external interests, negatively effecting the democratization of the conversation for local citizens.

Furthermore, South Korean federal government has recently re-focused their attention on welfare, demonstrating that whilst locally urban transformation provides economic benefits, it has numerous consequences that if not initially considered will undermine its initial positive economic capabilities and create a reactive cycle of policy.

Proactive Policy for Fragility Mitigation

In the face of continuing globalization and rising urbanization, it is increasingly attractive for cities to prioritize the higher-level compacts. The examples mentioned highlight the numerous issues that arise from prioritizing prosperity and integrity compacts ahead of the fundamental needs of citizens. Importantly, it demonstrates the reactive policy cycle that occurs when governments fail to consider the hierarchy of social compacts.

Using this Social Compact framework, we can understand cities as a continuing process, of which agreements between citizens and state must be continually balanced. Cities are evolving, dynamic areas and understanding their fragility allows us to maintain a continued discussion capable of adapting as the city evolves. Rather than reacting in the face of city crises, we utilize this framework to understand cities’ evolving dialogue and adapt accordingly.

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

Đăng nhận xét