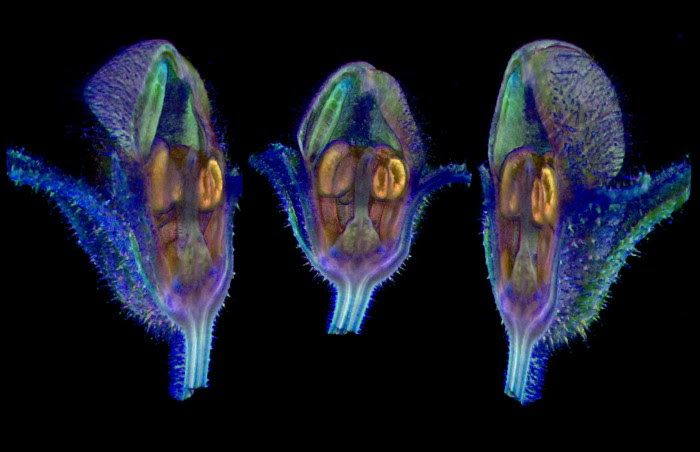

3D imaging offers new views of these antirrhinum (snapdragon) buds. Credit: Karen Lee/Xana Rebocho/John Innes Centre

Kellogg had graduated near the start of a revolution in plant biology. Over the next few decades, as researchers adopted molecular tools and DNA sequencing, detailed analyses of plants’ physical traits fell out of fashion. And because many geneticists worked with only a few key organisms, such as the thale cress Arabidopsis thaliana, they didn’t need expertise in comparing and contrasting different plant species. At universities, botany departments folded and molecular-biology departments swelled. Kellogg, now at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center in St Louis, Missouri, adapted: she embraced genomics, and combined it with her morphology skills to trace the evolution of key traits in the wild relatives of food crops.

But lately, Kellogg has noticed a resurgence of interest in the old ways. Advances in imaging technology — allowing researchers to peer inside plant structures in 3D — mean that biologists are seeking expertise in plant physiology and morphology again. And improvements in gene editing and sequencing have liberated geneticists to tinker with DNA in a wider range of flora, giving them a renewed appetite to understand plant diversity.

Plant biologists hope that, by combining new approaches to botany with data from genomics and imaging labs, they can provide better answers to questions that biologists have asked for more than 100 years: how genes and the environment shape the rich diversity of plants’ physical forms. “People are starting to look beyond their own system into plants as a whole,” says Kellogg. Plant morphology was once a science of form for its own sake, she says, but now, it is being pressed into service to understand how plant traits connect to gene activity across disparate species. “It’s coming back — just under different guises.”

Đăng nhận xét