To pressure polluters, the new trading system must avoid being too generous with permits, writes Huw Slater

The structure for the market’s operation has been in preparation for some time and has now received sign-off from the State Council. The ETS will have a three-stage implementation process to provide a smooth transition from the seven pilot markets that began in five cities and two provinces in 2013-14.

The establishment of a national ETS comes at a crucial time of global interest in China’s climate action. The intention of the United States to withdraw from the Paris Agreement sparked fears that other countries would backtrack on commitments to reduce emissions.

The road to the big launch

Preparations for the market intensified after President Xi Jinping announced in 2015 that China would launch the ETS by 2017.

For those companies that emit a lot of carbon dioxide, it became a requirement to report their historical emissions data, which will be subject to independent verification. The reliability of this process is important for the integrity of the market. Without confidence in data reporting, companies may be reluctant to invest in a market that does not ensure a level playing field.

Making sure that stakeholders in the carbon market understand its requirements has also been underway through training. This will be strengthened with the establishment of regional training centres in a number of provinces.

To begin with, the system will cover major emitters in the electricity generation sector. Other sectors of the economy that are large sources of emissions will join in the coming years. Even limited to the power sector, China’s ETS will still be the largest market in the world by a wide margin, covering about twice the emissions as the European Union ETS.

Allowance allocation

Draft allocation plans for three sectors (power, cement and aluminium) were released in May 2017. The plans specify benchmarks and the methodology for determining which generators can receive up to 100% of their allowances under the ETS for free. For companies that emit more than their allowance allocation, additional permits must be purchased on the market

For the national carbon market to be successful it’s important that the allowance of permits is not too generous, otherwise demand for permits will be dampened and polluters will have limited incentive to reduce emissions. On the other hand, if allowance allocation is too strict then the costs for industry may be too severe.

As the first sector covered and the largest source of carbon emissions, power generation will form the core of the carbon market. The power sector has the most reliable dataset for historical emissions, making allocation of allowances easier. The other key emitting sectors are currently in the process of establishing these datasets, and will thus be included in the national scheme at a later date.

The trial allocation methodology released in May set eleven benchmarks for different types of power plant. For less efficient plants, such as those with small coal turbines, the benchmark is higher than average.

Allocation should ideally incentivise companies to retire or scale-down inefficient plants first because it will be cheaper to do so. For example, provinces such as Shandong, Henan and Inner Mongolia each have a substantial fleet of the smallest and least efficient coal-fired power plants. These plants also make up a big part of the power generation capacity in the north-east (Jilin, Heilongjiang and Liaoning). Because the coal power sector represents a significant part of the economy in these northern provinces, internal negotiation over the past months has focused on how generous the allocation of permits should be for different regions. Administrators must balance avoiding excessive costs for industry, while ensuring that low-cost emissions reduction is adequately incentivised.

Room for higher carbon prices

The fact that prices for purchasing additional allowances in the pilot carbon markets are often lower than expected suggests that there is room for more ambition on the part of authorities.

China Carbon Forum conducts a biennial China Carbon Pricing Survey, and we recently published the 2017 instalment, summarising the views from 260 key stakeholders about the future of carbon pricing in China, including consultancies, industry, academia, the finance sector, trading platforms and non-governmental organisations.

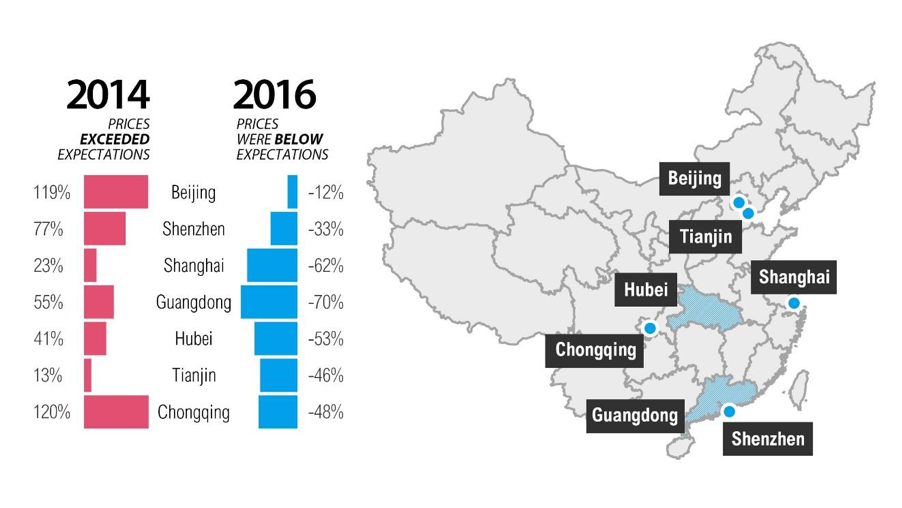

Past surveys show that while respondents expected carbon prices to increase from 2014 to 2016 they actually decreased, indicating an overabundance of allowances in the market that pushed prices down.

Difference between average prices in China's pilot ETSs in 2014 and 2016 and expectations in the 2013 and 2015 China Carbon Pricing Surveys respectively. Source of market price data: SinoCarbon

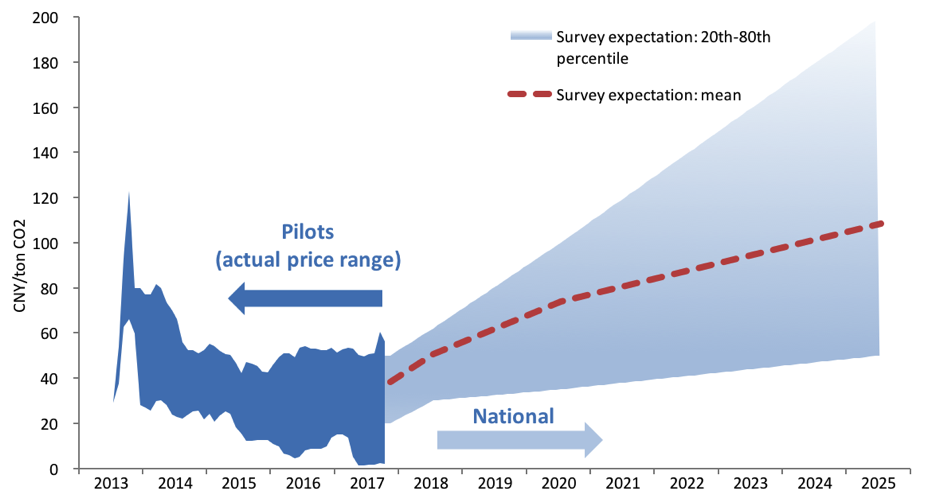

Nevertheless, the 2017 survey found that respondents still think that prices will go up. On average, they expect that when the national market starts, prices will be higher than the current average for the seven pilots (38 yuan/tonne, or US$5.8), rising to 74 yuan/tonne (US$11) in 2020 and 108 yuan/tonne (US$16) in 2025.

Range of prices in the pilot systems to-date, and estimated prices for the national system by survey respondents

The survey also revealed that industry respondents expect higher prices than non-industry ones. Similar surveys conducted in Europe and Australia tended towards lower carbon price expectations from industry. However, our 2015 survey also showed an industry tendency to expect higher prices in China. This result, again, suggests that the government can be more ambitious in the system’s design.

Impact on carbon pollution

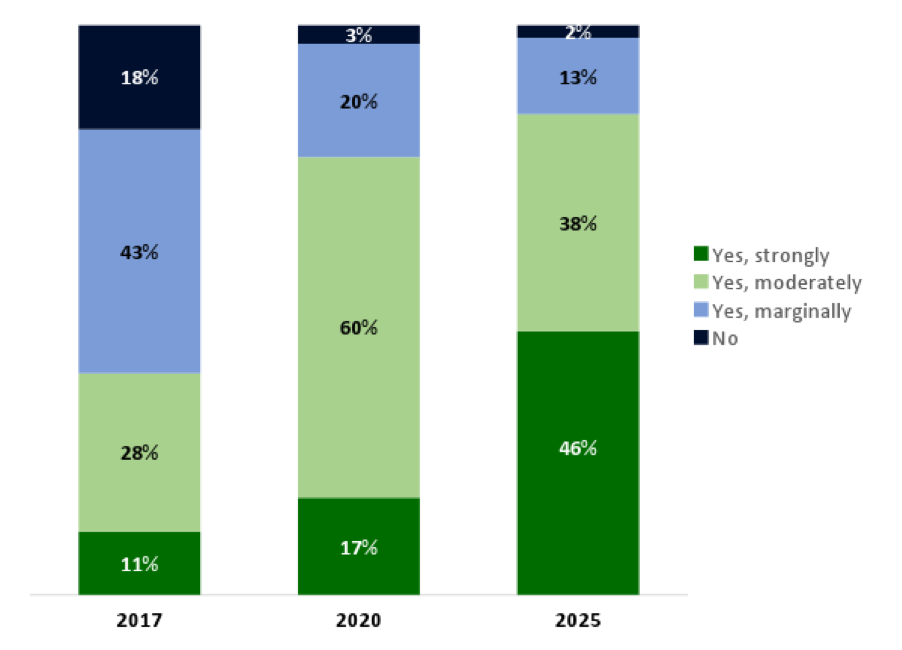

As the key goal of an ETS is to reduce carbon emissions, the survey provides a source of optimism, as respondents expect trading of carbon emissions to increasingly affect investment decisions in coming years. In 2017, 38% of respondents expect investment decisions to be strongly or moderately affected, and by 2025 this figure rises to 75%.

The responses also show there is uncertainty in the medium-term, with fewer respondents expecting a strong impact in 2020 than for the 2015 survey (17%, down from 30%). This can partly be attributed to the lack of clarity that has existed throughout 2017 regarding the precise starting date and legal basis for the system.

However, in the long-term, confidence remains high that the ETS will play an important role in shifting investment towards a low-carbon pattern.

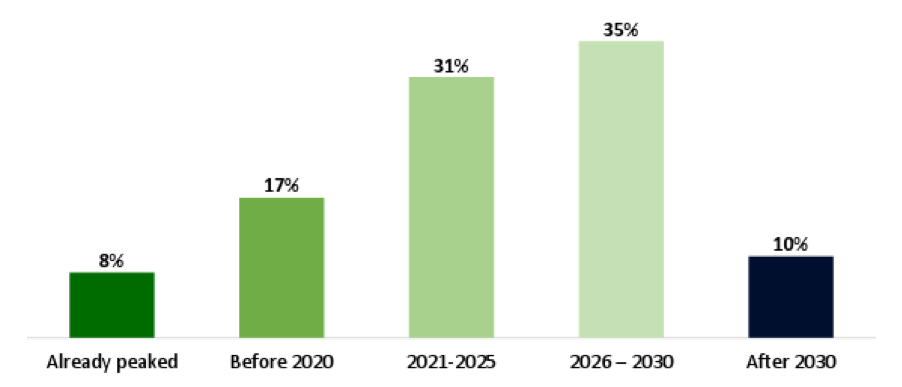

China has committed to peaking its carbon emissions by 2030. Of the survey respondents, 90% expect the target will be achieved, and 55% think it will be met by 2025 or earlier. Interestingly, 8% of respondents estimated that China’s carbon emissions had already peaked. Recent data released by the Global Carbon Budget suggest that China’s emissions may rise by about 3.5% from last year, but it is encouraging that an increasing proportion of stakeholders see the peak date coming much earlier than 2030.

Power sector reform

While the national carbon trading system will increasingly impact on the economics of power generators, the lack of flexibility in electricity prices in China means there is little incentive for other consumers to save energy.

Several of the pilot regions worked around this by obligating large power consuming institutions to join the carbon market but the national system won’t follow this approach. However, recent efforts to reform electricity pricing provide an opportunity for the carbon price to be passed on to other consumers in future. In particular, provinces such as Guangdong and Zhejiang are taking steps to establish the basis for short-term power generation rights trading.

With more flexibility in electricity price setting, there should eventually be space for generation companies to pass the carbon cost on to large electricity consumers. Hopefully these reforms will quickly be taken up by other large power-consuming provinces such as Shandong and Jiangsu. In this way, the implementation of the carbon market and power market reforms can be mutually re-enforcing.

Now more than ever…

chinadialogue is at the heart of the battle for truth on climate change and its challenges at this critical time.Our readers are valued by us and now, for the first time, we are asking for your support to help maintain the rigorous, honest reporting and analysis on climate change that you value in a 'post-truth' era.

Đăng nhận xét