The Green Climate Fund Board is considering

results-based payments for protecting and restoring tropical forests,

which is good news for the climate and for developing countries, says

Jonah Busch of the Center for Global Development. In a recent blog, he

describes two components the GCF should – and can – get right.

Originally posted on the Center for Global Development blog.

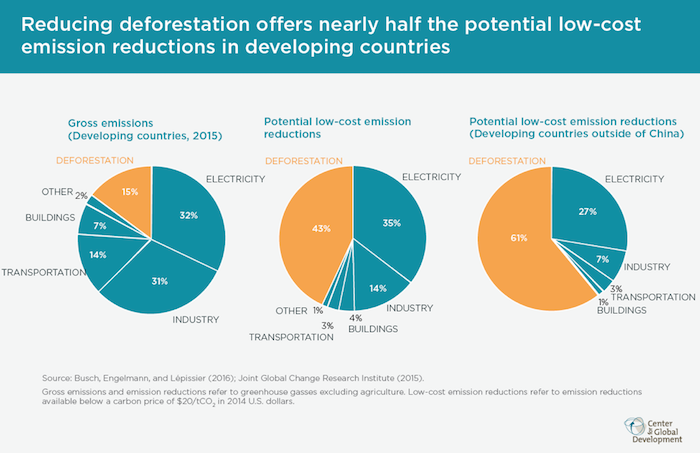

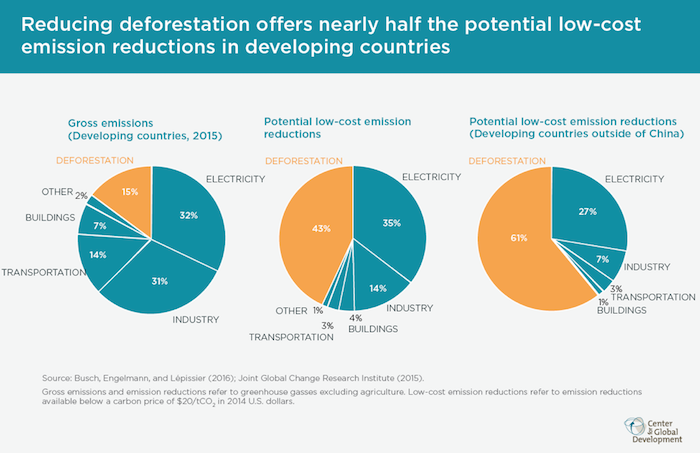

27 April 2017 | The Green Climate Fund (GCF) could begin offering results-based payments for protecting and restoring tropical forests as early as July. That’s good news for the climate and for developing countries, where tropical deforestation can be nearly half of low-cost emission reductions. Yet funding to protect forests remains low and slow, as Frances Seymour and I explain in our book, Why Forests? Why Now? As the GCF moves to enable results-based payments for forests, earlier initiatives offer valuable lessons on two things the GCF should—and can—get right: 1) keep rules simple, and 2) recognize that institutional procedures built for upfront investments may not always be appropriate for results-based payments.

So far the GCF has approved 43 projects for climate mitigation and adaptation, totaling $2.2 billion in grants and loans. Two of these projects involve forests protection—$41 to finance Ecuador’s REDD+ action plan, and $53 million for smallholder farmers in Madagascar’s eastern rainforests. But the GCF hasn’t yet moved to systematically enable results-based payments for reducing emissions from deforestation (REDD+). It looks like that’s about to change.

When the GCF Board meets this July, it could issue a request for proposals for tropical countries to apply for results-based payments for reducing emissions by protecting and restoring forests. Last week in Bali the GCF convened a meeting of board-nominated REDD+ experts to discuss what might go into that request for proposals. I was invited to this meeting as a facilitator.

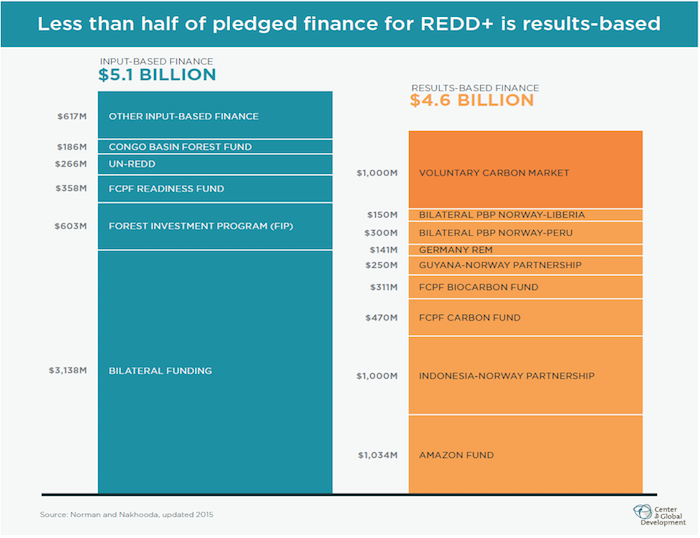

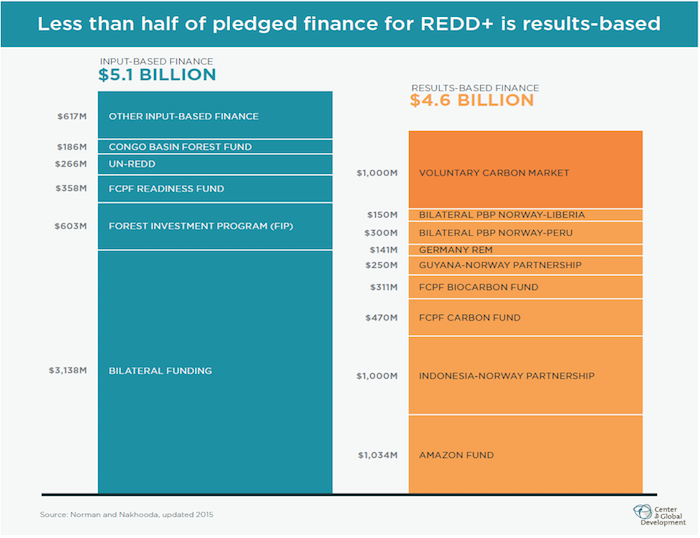

If the GCF enables results-based payments, it will join a diverse public funding landscape for REDD+ of about $8.7 billion from 2006-2015. More than half of this funding has been for inputs—readiness and policies. Less than half pays for results, including bilateral agreements of Brazil, Guyana, and Indonesia with Norway, and the multilateral Carbon Fund. The roughly $1 billion per year pace looks set to continue with an announcement in Paris in 2015 by Germany, Norway, and the United Kingdom of $5 billion, with the bulk of that on a results-basis.

Private finance for REDD+ makes up only about $1 billion, coming in the form of companies voluntarily offsetting their emissions. This amount is far less than anticipated a decade ago when it appeared reasonably likely that cap and trade programs in the United States and elsewhere would pass and would allow regulated companies to meet a portion of their emission-reduction obligations by purchasing REDD+ offsets. A carbon-neutral growth agreement by the International Civil Aviation Organization looks set to include offsets that could potentially include REDD+. However, a market for tropical forest offsets in California remains in political limbo, as my colleague Michele de Nevers describes.

GCF is a very important addition to the financial landscape for REDD+ because it is the only institution directly responsible to the mandate of the UNFCCC, with the legitimacy and balanced governance that comes along with universal representation of countries. The 2015 Paris climate agreement included a prominent role for protecting and restoring forests through results-based payments for REDD+; the GCF is the most direct way to operationalize that part of the agreement.

As a relative latecomer to the REDD+ finance landscape, GCF has the benefit of being able to learn a lot from earlier funds, both in terms of valuable precedents and cautionary lessons.

Any results-based payment program needs rules. Reference levels provide a benchmark for measuring success in reducing emissions; social safeguards prevent harm to indigenous peoples. At this point the issues around such rules have been thoroughly discussed, and different REDD+ initiatives have taken different approaches, as detailed in Why Forests? Why Now?

In hindsight, one reason the Carbon Fund became complicated and slow was its desire to craft rules that could work for both carbon markets and public funds. Each is complicated in its own way—market designers typically ask for sophisticated carbon accounting rules to ensure the environmental integrity of offsets; public funders tend to ask for elaborate rules to minimize the risk that funds from their taxpayers will be misused. Trying to meet both sets of donor demands in a single set of rules led to complexity. The cost of complication is delay, burden on forest countries, and discouraging the submission of worthy applications.

GCF has more than twice as many principals (a 24-country board, divided evenly between developed and developing countries), so is it doomed to be even more complicated? Not necessarily. GCF has a big advantage over the Carbon Fund that it can choose to set rules only for public funding, and leave aside for now rules related to tradeable credits. Furthermore, to the extent that overcomplication at the Carbon Fund emerged from donors operating in a recipient-free rulemaking environment, the GCF’s 50-50 board structure has the potential to bring more balance. During the GCF’s expert workshop I was encouraged to see participants trying to operationalize decisions already made by the UNFCCC rather than setting up duplicative rulemaking processes.

The same issue of heavy upfront documentation versus lighter ongoing assessment and planning appears likely to crop again at the GCF, which applies the safeguards of the International Finance Corporation, and requires planning documents of its upfront investments. However, The GCF might have some advantages over the Carbon Fund when it comes to processes that accommodate results-based payments. It’s a new institution, its mandate includes results-based finance, and such programs could potentially become a significant portion of its portfolio. I’m hopeful that the GCF can find ways to extend flexibility to results-based payments programs in recognition of their differing needs.

Upfront predictions of eventual project successes shouldn’t be confused with true results, and they certainly shouldn’t prevent the GCF from offering a blend of across upfront and results-based finance. Indeed the concept of “multiple phases of REDD+” was agreed to encourage exactly this blend to occur. My colleague Bill Savedoff has written more about issues around “double counting,” as part of a larger body of work on cash-on-delivery approaches to development finance that also includes analysis on results-based payments for forests, including at the GCF.

By enabling results-based payments this year, the GCF can give a much-needed financial boost to tropical countries’ efforts to fight climate change by protecting and restoring forests.

Jonah Busch is a Research Fellow at the Center for Global Development with a focus in forests, land-use change and climate. He can be reached at jbusch@cgdev.org.

27 April 2017 | The Green Climate Fund (GCF) could begin offering results-based payments for protecting and restoring tropical forests as early as July. That’s good news for the climate and for developing countries, where tropical deforestation can be nearly half of low-cost emission reductions. Yet funding to protect forests remains low and slow, as Frances Seymour and I explain in our book, Why Forests? Why Now? As the GCF moves to enable results-based payments for forests, earlier initiatives offer valuable lessons on two things the GCF should—and can—get right: 1) keep rules simple, and 2) recognize that institutional procedures built for upfront investments may not always be appropriate for results-based payments.

Progress on forests at the Green Climate Fund

The GCF is a financial institution created by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 2011, with headquarters in Songdo, Korea. It aspires to finance not just a collection of climate-friendly projects, but a “paradigm shift towards low-emission and climate resilient development.” The GCF has received more than $10 billion in pledges to date, though when the US will follow through with $2 billion remaining from its Obama-era $3 billion pledge appears uncertain as this funding was not included in the President’s budget request to Congress.So far the GCF has approved 43 projects for climate mitigation and adaptation, totaling $2.2 billion in grants and loans. Two of these projects involve forests protection—$41 to finance Ecuador’s REDD+ action plan, and $53 million for smallholder farmers in Madagascar’s eastern rainforests. But the GCF hasn’t yet moved to systematically enable results-based payments for reducing emissions from deforestation (REDD+). It looks like that’s about to change.

When the GCF Board meets this July, it could issue a request for proposals for tropical countries to apply for results-based payments for reducing emissions by protecting and restoring forests. Last week in Bali the GCF convened a meeting of board-nominated REDD+ experts to discuss what might go into that request for proposals. I was invited to this meeting as a facilitator.

If the GCF enables results-based payments, it will join a diverse public funding landscape for REDD+ of about $8.7 billion from 2006-2015. More than half of this funding has been for inputs—readiness and policies. Less than half pays for results, including bilateral agreements of Brazil, Guyana, and Indonesia with Norway, and the multilateral Carbon Fund. The roughly $1 billion per year pace looks set to continue with an announcement in Paris in 2015 by Germany, Norway, and the United Kingdom of $5 billion, with the bulk of that on a results-basis.

Private finance for REDD+ makes up only about $1 billion, coming in the form of companies voluntarily offsetting their emissions. This amount is far less than anticipated a decade ago when it appeared reasonably likely that cap and trade programs in the United States and elsewhere would pass and would allow regulated companies to meet a portion of their emission-reduction obligations by purchasing REDD+ offsets. A carbon-neutral growth agreement by the International Civil Aviation Organization looks set to include offsets that could potentially include REDD+. However, a market for tropical forest offsets in California remains in political limbo, as my colleague Michele de Nevers describes.

GCF is a very important addition to the financial landscape for REDD+ because it is the only institution directly responsible to the mandate of the UNFCCC, with the legitimacy and balanced governance that comes along with universal representation of countries. The 2015 Paris climate agreement included a prominent role for protecting and restoring forests through results-based payments for REDD+; the GCF is the most direct way to operationalize that part of the agreement.

As a relative latecomer to the REDD+ finance landscape, GCF has the benefit of being able to learn a lot from earlier funds, both in terms of valuable precedents and cautionary lessons.

Make rules as simple as possible (but no simpler)

The most similar institution to the GCF—and thus the most valuable for learning—is the $736 million Carbon Fund, a multilateral consortium of 11 donors housed in the World Bank. I’ve previously written about my hopes and questions for the Carbon Fund in 2013, as well as its frustratingly slow pace of progress as of 2016, based on my experience as a technical advisor during the creation of the fund’s rulebook, the Methodological Framework. (As of today the Carbon Fund has started or will soon start negotiations on results-based payment agreements with Costa Rica, Democratic Republic of Congo, Chile, and Mexico, and has an additional 15 programs in its “pipeline.”)Any results-based payment program needs rules. Reference levels provide a benchmark for measuring success in reducing emissions; social safeguards prevent harm to indigenous peoples. At this point the issues around such rules have been thoroughly discussed, and different REDD+ initiatives have taken different approaches, as detailed in Why Forests? Why Now?

In hindsight, one reason the Carbon Fund became complicated and slow was its desire to craft rules that could work for both carbon markets and public funds. Each is complicated in its own way—market designers typically ask for sophisticated carbon accounting rules to ensure the environmental integrity of offsets; public funders tend to ask for elaborate rules to minimize the risk that funds from their taxpayers will be misused. Trying to meet both sets of donor demands in a single set of rules led to complexity. The cost of complication is delay, burden on forest countries, and discouraging the submission of worthy applications.

GCF has more than twice as many principals (a 24-country board, divided evenly between developed and developing countries), so is it doomed to be even more complicated? Not necessarily. GCF has a big advantage over the Carbon Fund that it can choose to set rules only for public funding, and leave aside for now rules related to tradeable credits. Furthermore, to the extent that overcomplication at the Carbon Fund emerged from donors operating in a recipient-free rulemaking environment, the GCF’s 50-50 board structure has the potential to bring more balance. During the GCF’s expert workshop I was encouraged to see participants trying to operationalize decisions already made by the UNFCCC rather than setting up duplicative rulemaking processes.

Recognize that results-based payments may need different procedures than upfront investmentsAnother reason the Carbon Fund became slow and complicated was the need for its programs to adhere not only to the rules noted above but also to various institutional requirements of the World Bank. The issue here is not that a financial institution would impose safeguards and due diligence processes on its projects—as indeed they should—but rather that institutional requirements set up to finance upfront investments may not always be appropriate for results-based payments.

Safeguards and due diligence

All programs in the World Bank must follow that institution’s safeguard procedures, which are long and detailed and must be completed upfront. Meanwhile, the UNFCCC negotiations agreed to a set of Cancun Safeguards in 2010, which number just seven, but are purpose-built for REDD+ and can be assessed continually. Similarly, as part of its due diligence process, the World Bank requires that investment proposers provide project documents that specify upfront and in great detail many aspects of the activities to be undertaken. But with results-based finance, specifying all plans in advance may suffocate the flexibility needed to learn by doing on the way to producing results.The same issue of heavy upfront documentation versus lighter ongoing assessment and planning appears likely to crop again at the GCF, which applies the safeguards of the International Finance Corporation, and requires planning documents of its upfront investments. However, The GCF might have some advantages over the Carbon Fund when it comes to processes that accommodate results-based payments. It’s a new institution, its mandate includes results-based finance, and such programs could potentially become a significant portion of its portfolio. I’m hopeful that the GCF can find ways to extend flexibility to results-based payments programs in recognition of their differing needs.

“Double financing”

Applicants for upfront investment finance from the GCF are asked to predict in advance how many tons of carbon dioxide their projects will keep out of the atmosphere. But these claims are speculative—there’s no way to truly estimate the emission reductions a project or program will achieve until after the fact, and even then it can be challenging to attribute results to any particular policy, program, or project. Predicting future benefits is even more challenging for forest projects than engineering projects such as solar plants or seawalls.Upfront predictions of eventual project successes shouldn’t be confused with true results, and they certainly shouldn’t prevent the GCF from offering a blend of across upfront and results-based finance. Indeed the concept of “multiple phases of REDD+” was agreed to encourage exactly this blend to occur. My colleague Bill Savedoff has written more about issues around “double counting,” as part of a larger body of work on cash-on-delivery approaches to development finance that also includes analysis on results-based payments for forests, including at the GCF.

Start now, and learn

The GCF has yet another advantage when it comes to results-based payments for forests: its requests for proposals can be easily modified in future iterations. Thus the GCF has every reason to issue a first request for proposals that helps it learn the ropes on paying for results, and then adapt as needed in subsequent requests.By enabling results-based payments this year, the GCF can give a much-needed financial boost to tropical countries’ efforts to fight climate change by protecting and restoring forests.

Jonah Busch is a Research Fellow at the Center for Global Development with a focus in forests, land-use change and climate. He can be reached at jbusch@cgdev.org.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.

Đăng nhận xét