The country needs to develop its domestic green finance industry, attract international investors and improve its overseas investments

It will be a gargantuan task for China to make good on its recent pledge to become carbon neutral by 2060. Currently, it contributes about 26% of global carbon emissions, its economy is still rapidly developing, and many of its sectors and regions are heavily dependent on fossil fuels.

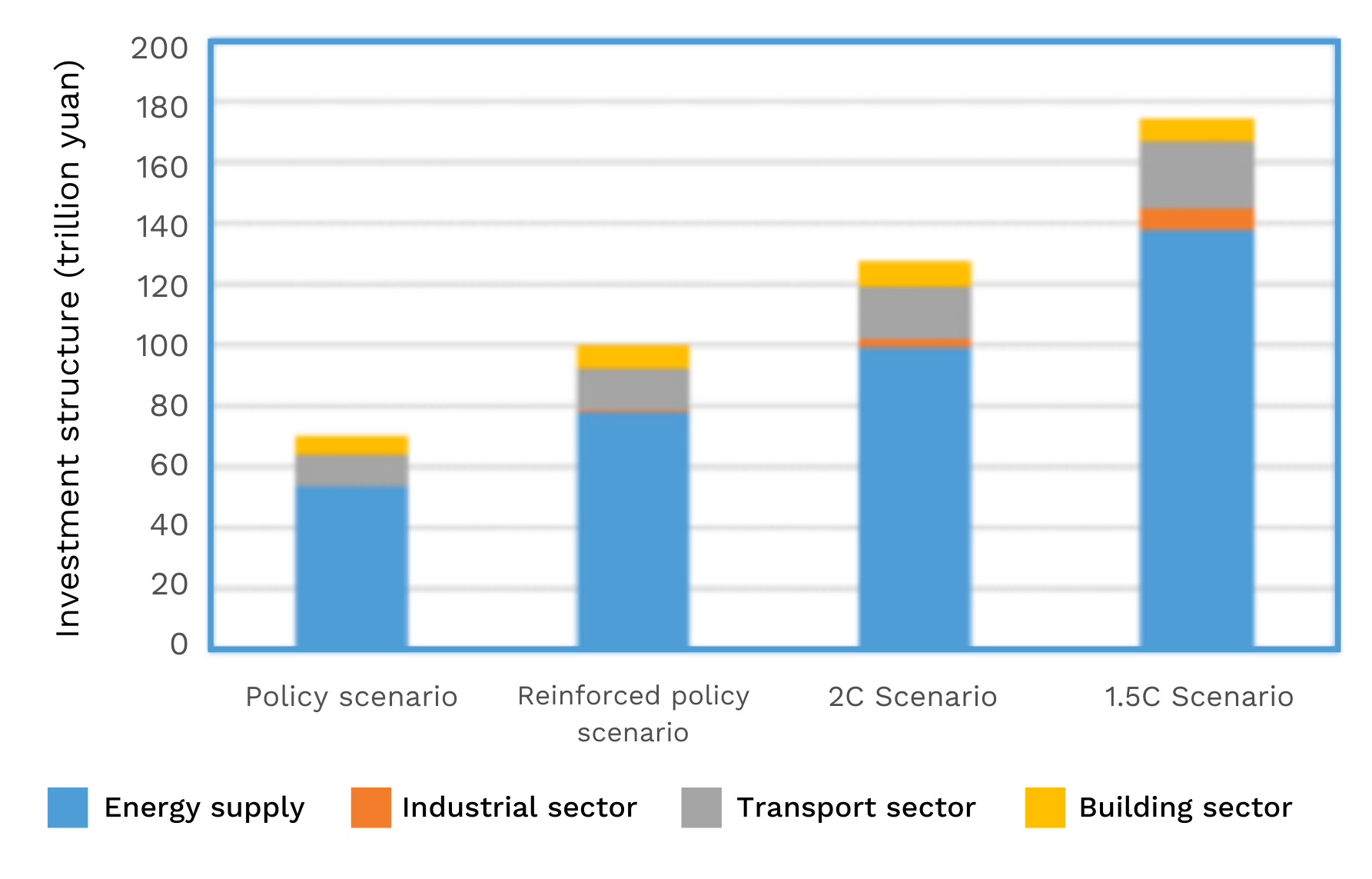

To achieve the target, new investment of around 138 trillion yuan (US$20 trillion) will be needed between 2020 and 2050 in the energy system alone, over 2.5% of annual GDP, according to a recent study from Tsinghua University’s Institute for Climate Change and Sustainable Development. On top of that, investments will be needed to make existing infrastructure resilient against the consequences of climate change.

China’s green finance sector will be key to mobilising and utilising these investments. The sector has enjoyed significant growth in recent years, but in the decades to come, green finance will need to do more than “catch up” if China is to successfully decarbonise its economy. To reach carbon neutrality by 2060, China will need to develop its domestic green finance industry and attract international investors. It also needs to improve its overseas investments, particularly within the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), to make its climate commitments credible to the international community.

Investment in China’s energy infrastructure in 2020-2050 under different scenarios

Green finance in China

Due to the size of its economy, it should be no surprise that China has quickly become the largest green finance market, with about 11 trillion yuan (about US$1.8 trillion) in green credit and about 1 trillion yuan (about US$190 billion) in green bonds by 2020. According to the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC), key sectors for green credits include green transportation (37%), emerging industries (about 21%), renewable energy (about 20%) and industrial energy saving (about 5%). Of the green bonds issued since 2016, 59% served multiple purposes (such as transportation, energy production and energy saving), while 13% were issued specifically for clean energy projects and 11% were for clean transportation.

Growing the green finance market has helped China control the pollution and ecological damage resulting from 40 years of breakneck economic growth. It has required setting green financial standards, incentive mechanisms, environmental information disclosure requirements, product innovation and local pilot projects.

These efforts were given a boost in 2012 when the CBIRC introduced its green credit guidelines for banks to provide credit to companies.

Then in 2015, the People’s Bank of China, the country’s central bank, issued green bond guidelines.

In 2016, seven ministries issued the “Guiding opinions on building a green financial system”.

In October of this year, “Guidance on promoting investment and financing to address climate change” (Climate Finance Guidance) was jointly issued by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, the National Development and Reform Commission, the People’s Bank of China, the CBIRC, and the China Securities Regulatory Commission.

China has also initiated and participated in several international forums promoting green finance, such as the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), and the Sustainable Banking Network.

Next steps at home

China’s green finance industry needs access to cheaper and more inclusive finance. At the annual meeting of China’s Green Finance Committee in September 2020, Chen Yulu, deputy governor at the People’s Bank of China, highlighted the need for systematic institutional arrangements to be made in the 14th Five Year Plan period (2021-2025) to improve green finance.

These include a green finance standard system to align green credit, green industry and green bond standards; a green finance performance evaluation system for financial institutions that goes beyond box-ticking to look at actual environmental outcomes; an extended green finance support policy toolbox to mobilise green and demobilise brown finance, including incentives and taxes; and expanded environmental information disclosure allowing for better decision-making.

Ma Jun, one of the most prominent figures in the development of green finance in China, also emphasised the need for guidelines for financial institutions on climate risk analysis. The Ministry of Ecology and Environment recently reiterated that the national carbon market must start as soon as possible, an ambition that was echoed in the Climate Finance Guidance released in October.

Attracting foreign investment

Foreign holdings in Chinese bonds have increased in recent years, but their share in China’s bond market has hovered at only 2.6%. Attracting more foreign investors will require lower transaction costs and further removal of barriers for foreign investors. China also needs to harmonise its own green finance standards with those of international markets in terms of classification, certification and evaluation of green financial products.

Greater harmonisation would attract more direct investment into green projects or the issuance of yuan-denominated bonds, so-called “panda bonds”. It would also encourage Chinese issuers to offer more yuan-denominated bonds abroad for projects in China as well as making it easier for China’s investors to invest into other markets.

The publication of a new green bond standard draft in May 2020 was a step in the right direction as it mostly excluded “clean coal”. The latest Climate Finance Guidance, however, stresses the application of the Green Industry Standard 2019, which continues to include “clean coal” and is thus less compatible with international standards.

Greening the Belt and Road Initiative

If China’s commitment to fighting global warming, as demonstrated by its 2060 domestic carbon neutrality pledge, is to be taken seriously, it should stop financing coal plants overseas, including in the more than 130 countries of the BRI.

The first half of 2020 saw – for the first time – a majority of non-fossil fuel energy investments under the BRI. China is emphasising green overseas investments through regulatory initiatives and voluntary approaches. The regulatory ambition has taken a large step forward in the Climate Finance Guidance, which states that China aims to “regulate offshore investment and financing activities” in line with climate goals as compared to the current requirement for Chinese investors to apply the often weak environmental standards of BRI host countries.

One crucial supporting piece of regulatory research is the “Greenlight System for the Belt and Road Initiative”, which the authors have been involved in developing. In an introduction of the Climate Finance Guidance, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment showed the ambition to classify BRI investments into “green”, “yellow” and “red” depending on their environmental risk and nature-positive contribution. This could allow the Chinese government to accelerate greening of the BRI and possibly hold investors more accountable for overseas environmental impacts.

In terms of sector-led approaches, the Green Investment Principles (GIP) are a voluntary set of seven high-level principles signed by 37 financial institutions to accelerate green BRI investments. The annual GIP report published in September showed how some signatories have embarked on integrating climate risks and laid out ambitions to catch up to more established standards, like the Equator Principles.

The questions ahead for green finance in China

Looking ahead, China’s green finance community has a lot of work to do. For instance, China’s carbon market has been promised since 2017, and while the new Climate Finance Guidance and the draft rules for a national emissions trading system published at the beginning of November promote the construction of carbon market mechanisms, a start to national trading has not yet been announced. Once the national carbon market launches, many investors will have to develop risk and investment strategies.

Another issue is how to shift the business model of some of the world’s largest state-owned enterprises, such as the China National Offshore Oil Corporation, Petrochina and Sinopec, whose profits are based on the extraction of fossil fuels. At the end of August, Petrochina surprised the market by announcing its aim to become near carbon neutral by 2050, but it isn’t yet clear how it will achieve this transition.

International partners in particular also wonder how China will provide fair access to markets and healthy competition given its accelerated preferential treatment of state-owned enterprises. This includes preferential access to finance through China’s massive policy banks, such as the China Development Bank, and state-owned (or state-linked) financial institutions, such as the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China and the Bank of China. This will be particularly relevant in providing green finance and applying green technologies and innovation, for example to the hydrogen sector.

Over the next months and years, we expect many pilots, promises and re-adjustments in the context of the 2060 carbon-neutrality goal. It is the proverbial “crossing the river by touching the stones”: while Xi Jinping’s pledge set a clear direction for policy, law, energy, industry, innovation and finance, many details will be drawn and re-drawn step by step. The pledge is a wake-up call for government and industry to adopt concrete plans. For green finance to play its role in helping China achieve its long-term carbon neutrality target, certainty is needed about opportunities and risks. This means ambitions need to be translated into targets as part of the 14th Five Year Plan, and in applicable and enforceable government policies on greening overseas investments.

Đăng nhận xét