Despite its negative reputation for heavy air pollution, Beijing is home to a stunning diversity of wildlife, especially birds. Some small steps could make this positive feature prevail.

The other day, I asked my friends and contacts for the first word that comes into their head when they hear “Beijing”. The most popular response from my non-Chinese friends was “pollution”.

China’s capital city has an image problem. Yet I believe Beijing – my home for the last ten years and whose people and wildlife I have grown to love – has the potential to demonstrate how a modern city can be designed and managed to make life better for humans and for nature. At the same time it could transform its image to the outside world.

Beijing’s biodiversity

It is little known that the municipality of Beijing is one of the best major capitals in the world for birds. It ranks second among G20 capitals, behind only Brasilia, in terms of the number of species recorded.

G20 capital cities by number of bird species recorded

| Rank | Country | City | Species recorded |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brazil | Brasilia | 539 |

| 2 | China | Beijing | 510* |

| 3 | Mexico | Mexico City | 495 |

| 4 | Argentina | Buenos Aires | 457 |

| 5 | India | Delhi | 456 |

| 6 | Japan | Tokyo | 449 |

| 7 | South Africa | Johannesbury | 428 |

| 8 | Indonesia | Jakarta | 408 |

| 9 | United Kingdom | London | 373 |

| 10 | Thurkey | Istanbul | 360 |

| 11 | Canada | Ottawa | 353 |

| 12 | United States | Washington DC | 347 |

| 13 | Italy | Rome | 314 |

| 14 | Australia | Canberra | 306 |

| 15 | Republic of Korea | Seoul | 293 |

| 16 | France | Paris | 281 |

| 17 | Saudi Arabia | Riyadh | 279 |

| 18 | Germany | Berlin | 260 |

| 19 | Russia | Moscow | 243 |

| 20 | European Union | Brussels | 219 |

Sources: eBird, Avibase and city birdwatching societies where available

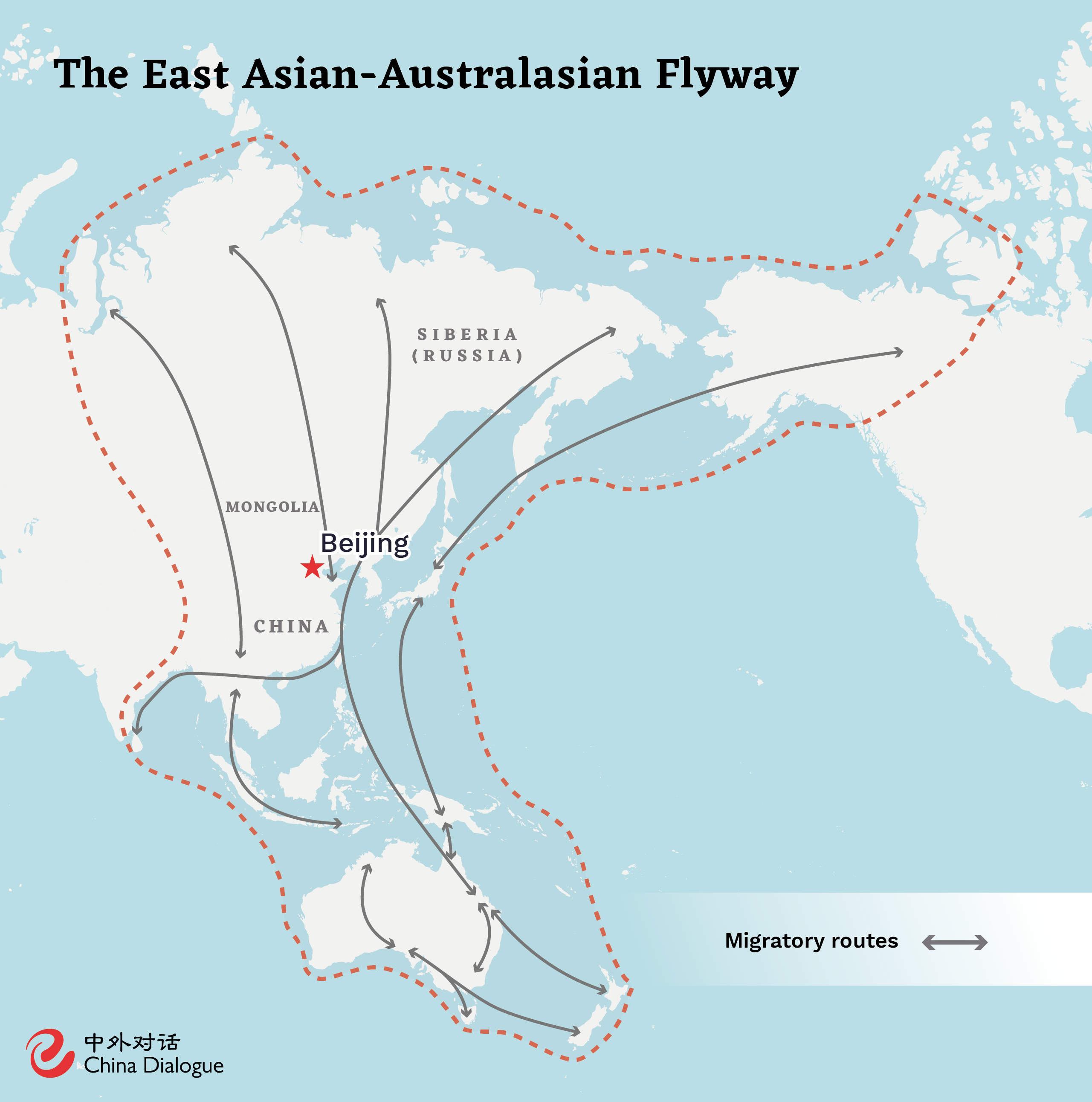

There are two reasons why Beijing is so good. First, its large size accommodates a variety of habitats with mountains, wetlands, grassland, forests and large parks. And second, and most importantly, its location. Beijing lies on a “bird superhighway” known as the East Asian-Australasian Flyway. One look at a map shows that, to the north of Beijing, there is a huge landmass – Siberia and Mongolia – dominated by taiga forest and, in the most northerly parts, tundra. In summer, there is an explosion of insects and millions of migratory birds fly north to take advantage of this high-protein food source to breed, raising more offspring, and more quickly, than if they stayed further south.

By winter, this area becomes inhospitably cold and the number of insects drops dramatically. So every autumn, there is a mass exodus of birds from northern latitudes, staggered from July (the earliest to move are the high Arctic breeding shorebirds, for whom the breeding season is just a few weeks) through to November (for the ducks, geese and cranes). Some will spend the winter in Beijing, others will go to southern China or Southeast Asia. Some fly as far as Australia and New Zealand and, as we have seen with projects to track the “Beijing Cuckoo” and the “Beijing Swift”, to Africa.

Most of these birds are nocturnal migrants and will pass over the capital undetected as we sleep (just put out a microphone pointing skyward on any night from late August to October and you’ll likely pick up lots of bird calls, providing a glimpse of the scale of migration over the city). However, some will stop in the capital, providing us with an opportunity to see them.

And of course, in spring, as the weather warms and the insects emerge, these birds flood back north, with Beijing again providing a stopover site. It is spring and autumn when Beijing becomes a world-class birding site.

It’s not only birds with which Beijing is blessed. Few major capital cities host populations of wild cats. In the mountains and wetlands of Beijing, there is a population of the Amur leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis euptilura). The common leopard (Panthera pardus), extirpated around the 1980s, is slowly heading back towards the mountains of West Beijing from its stronghold in the Taihang Mountains of nearby Shanxi Province. We can expect the first image of a common leopard in Beijing for decades, most likely from an infrared camera, in the next few years. Wild boar (Sus scrofa), Siberian roe deer (Capreolus pygargus), hog badger (Arctonyx collaris), Asian badger (Meles leucurus), raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides), squirrels and chipmunks, as well as the mystical Siberian weasel (Mustela sibirica), can all be found. Beijing also has more dragonfly and damselfly species (60) than the whole of the UK (57).

Threats to Beijing’s biodiversity

Beijing’s rich biodiversity cannot be taken for granted. It faces a number of threats, including the following.

First, habitat loss and degradation resulting from urban development taking little or no account of biodiversity and ecologically important sites. Second, land management policies such as clearing of vegetation and covering with plastic netting (to prevent fire and dust), which deprive migrant birds of an important food source (seeds) and put microplastics into the soil. And third, illegal poaching primarily for the cage bird trade and exotic meat, which is ongoing across the municipality despite improved law enforcement in the last ten years.

A ‘blueprint for biodiversity’ in Beijing

To preserve Beijing’s strong foundation of biodiversity, the city could develop a blueprint for biodiversity, embedding the interests of wildlife and wildlife habitats into decision-making and setting targets related to key native habitats and species.

The first step must be to conduct a thorough biodiversity “audit” to better understand what the city has and to develop a baseline from which to measure progress. In addition to this, below are four practical ideas that could help strengthen the protection of wild places, restore habitats and engage the public. Importantly, these ideas do not require significant resources; in fact, they could generate resources for some of the poorest communities in the capital, as well as helping to raise awareness of biodiversity and improve the quality of life of its residents.

1. Allowing parks to be ‘10% wild’

Beijing’s parks are impressive and a huge positive feature of the city landscape. They are also important refuges for wildlife. However, they could be significantly better. A suggestion is to leave “wild” 10% of each park, meaning that plants would be allowed to grow without being cut, leaves allowed to drop and decompose, providing shelter for insects, and wildlife allowed to thrive. This 10% would not affect the overall look of the parks and, if signs and other information were erected, the initiative would serve as a positive addition to the parks by educating the public about nature. Each park could partner with a local school or schools who could monitor the wildlife in the parks and compare the “wild” areas with those managed in the traditional way, with the results published on interpretation boards in the parks. If successful, the percentage could be expanded. The Beijing government has recently agreed to pilot this idea in one or two parks next year.

2. Miyun reservoir: potentially a world-class wetland reserve

The Miyun reservoir is a major drinking water source in the northeast of the capital and a vital site for migratory birds, including cranes. Currently the site is being managed for water quality only, at the expense of wildlife. Important native shrubs and seed-yielding plants – vital food for many small birds in winter – have been ripped out and replaced by inappropriate tree planting.

The city could change the way this wonderful site is managed. Water quality would still be prioritised but the reservoir could also be a world-class wetland nature reserve, partly open to the public, with boardwalks, bird hides and an information centre, bringing millions of yuan to the local community.

England’s largest reservoir – Rutland Water – is managed for water quality, as a nature reserve and for public recreation using a zoning system. The nature reserve brings millions of pounds to the local economy as more than one million people visit every year, staying in local hotels, eating in local restaurants and using local services. Water quality is not adversely affected.

To consider these ideas, the Beijing government has now established a working group, which is making a preliminary visit to the reservoir this month.

3. A ‘wild ring road’

Beijing is organised into concentric ring roads. A “wild ring road” – a circle of unmanaged land that runs outside the sixth ring road – could link a variety of habitats from mountains in the west to woodland, grassland, rivers and wetlands around the city, acting as a haven and a corridor for wildlife. The wild ring road could include limited public access via a cycling and walking “capital circular route”, served by public transport at key spokes, thus creating a wonderful leisure opportunity for walkers and cyclists, as well as a home for wildlife.

4. Public engagement: voting for Beijing’s municipal bird

Public awareness is key to building support for biodiversity conservation policies. To celebrate Beijing’s more-than 500 bird species, residents could be invited to vote for a “municipal bird”, with the results announced by the mayor ahead of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity next year. Up to five candidate species could be nominated, each championed by an “ambassador” (for example, a celebrity or a school) and promoted by the media.Such an initiative would raise public awareness, cultivate a sense of pride and build support for policies to protect the city’s biodiversity.

Beijing’s opportunity in a global context

Globally, we are experiencing one of the most dramatic extinction episodes in history. Scientists estimate that we are losing species at around a thousand times the natural rate. If we continue on this trajectory, 30 to 50% of all species may be lost by the middle of this century, presenting profound risks to human prosperity and wellbeing.

Next year, representatives from more than 160 countries will meet in Kunming, Yunnan, under the auspices of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, to agree on a “new deal for nature”. However, national governments alone cannot tackle the biodiversity crisis. Home to more than half of the global human population, cities have a vital role to play in connecting people to nature, changing mindsets and developing innovative ways to make our infrastructure and homes good for nature as well as people.

As the capital city of the host country of these vital UN biodiversity negotiations, with a population of over 20 million and home to impressive biodiversity, Beijing is well-placed to lead.

Ten years from now, when I repeat my experiment, wouldn’t it be wonderful if the most common response was not “pollution” but “green”, “nature”, or “biodiversity”?

Đăng nhận xét