We spoke to Lo Sze Ping, who recently left his post as CEO of WWF China, about the changes he has seen in China’s environmentalism since 2000

Since moving from Hong Kong to work for green NGOs in Beijing, Lo has seen China’s environmental movement go from the early days of “planting trees, watching birds and picking up litter” to the elevation of “ecological civilization” to a national strategy.

Having just left his post as CEO of WWF China, Lo Sze Ping recalls that when he first moved to Beijing, China had joined the WTO and “the power of reform and opening up was still being released.” Lo views the Chinese environmental movement within a larger historical context, with the tension between the local and the global an important theme.

In the early 2000s, he led Greenpeace’s arrival in China, integrating an organisation known for its non-violent direct action into the Chinese environmental movement, exposing to public criticism the deforestation of Yunnan by foreign companies and the exporting of waste to Guangdong by multinationals. He was also engaged in the environmental assessments for the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games and the 2010 Shanghai World Expo, proposing a framework for assessing China’s environmental performance in the context of its stage of development. He went on to become secretary general of SEE Conservation, founder of Greenovation Hub and executive board chair of Friends of Nature, as he looked for a route for the Chinese environmental movement that differed from the thinking of Western organisations. In 2013, when he took charge of WWF China, he found another opportunity to integrate his international and local experiences in his work. In 2020, he decided he had “completed his mission in the mainland” and will, after he leaves WWF at the end of September, help establish a foundation to fund grassroots environmental NGOs in the Global South.

In an interview with China Dialogue before he left Beijing, Lo said that “Chinese environmental NGOs should respond to China’s developmental reality with a sense of agency.”

China Dialogue: Can you describe Chinese society back in the early 2000s?

Lo Sze Ping: When I came to work in Beijing in 2000, China hadn’t joined the WTO, although the negotiations were underway. The wave of reforms unleashed by Deng Xiaoping’s 1992 Southern Tour were gathering pace and by the late 90s, from an economic perspective, China was an arrow ready to be fired.

China wasn’t yet the factory of the world and the Pearl River Delta [where I came from] was still working to a cheap-labour and high-pollution growth model, which attracted investors from nearby Hong Kong, but not yet many multinationals.

If we think of the late Qing and early Republican period as China’s first wave of industrialisation, and the post-1949 years as the second, then joining the WTO marked the start of the third wave – and I arrived just as that was starting. Its negative side – large-scale pollution – hadn’t yet been noticed. Of course, there were some local pollution issues, but it wasn’t something the whole country was aware of.

And what about the environmental movement back then?

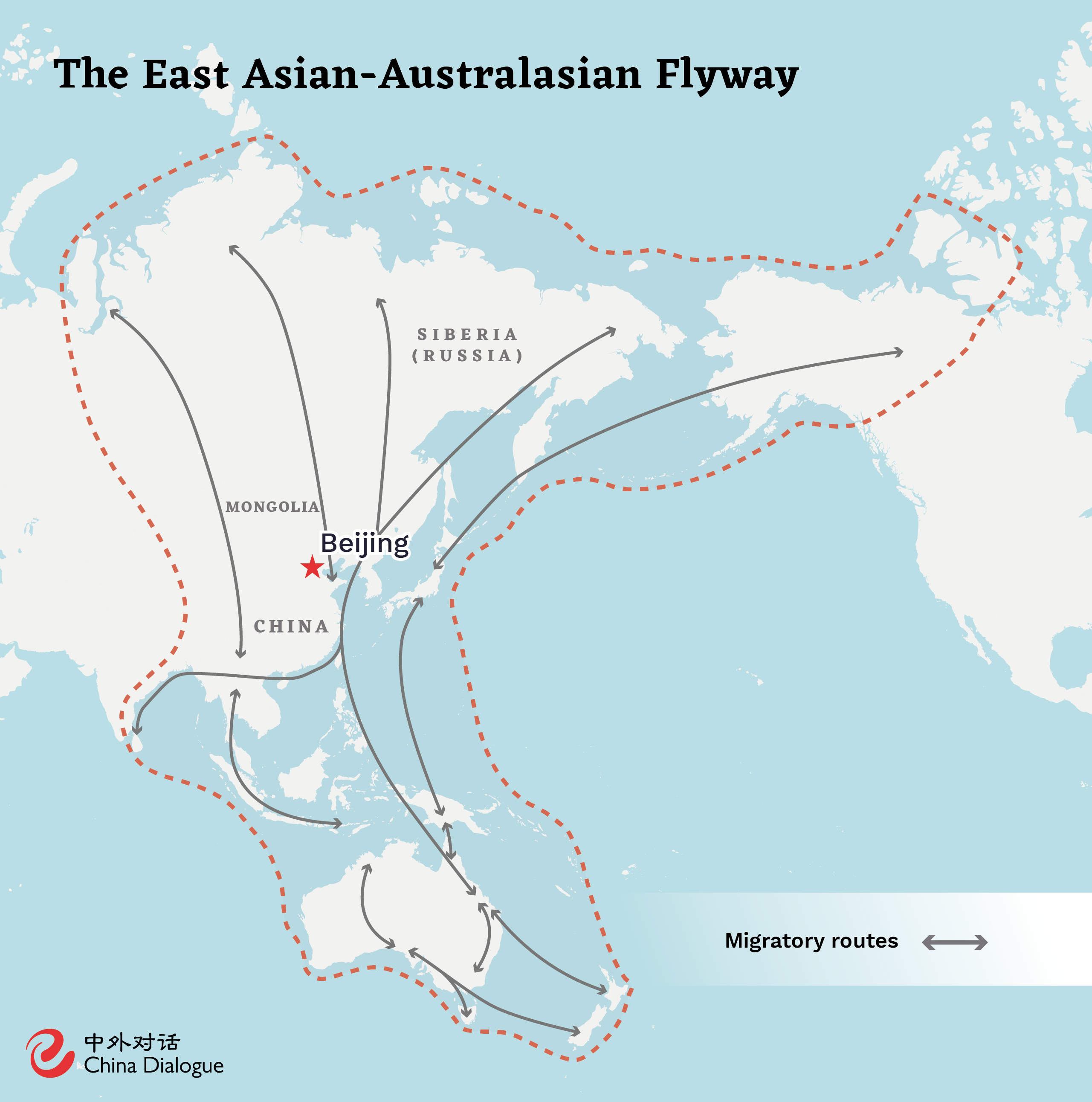

When I got to Beijing I met up with two people. The first was Liang Congjie, who founded Friends of Nature, the second was Jim Harkness, who at the time was China country director for WWF. At that time, these were the two most active, most visible people in the movement. There were barely any international environmental NGOs here, but WWF had been working on panda conservation since the 80s and had become very influential. This was just after the Yangtze floods of 1998, and the National Forestry Administration gave the WWF the opportunity to work on conservation along the river. There were human factors behind that once-a-century flood, and the WWF’s suggestions: stopping deforestation upstream, preventing more soil erosion, protecting river and coastal wetlands, and integrated river basin management, were all later adopted as national policy. I think WWF would have just been starting its freshwater projects – river basin management and wetlands conservation – in 2000, when I met with Jim Harkness.

I have very clear memories of calling on Liang Congjie. Looking back, I seem young and ignorant, but I thought the work Friends of Nature did, such as on-campus education, was too basic. I remember in the following years I would tell people that the Chinese environmental movement needed to move beyond educating the next generation – as the damage was already being done, on our generation’s watch, and we should concentrate our efforts on stopping that. I didn’t have the wisdom to take a more mature, longer-term view. Chinese environmentalism needs to be tenacious, to work bit by bit and achieve results over time.

Environmentalism was very weak back then, but there was work on conservation of the black-necked crane in the north-east and Wu Dengming was trying to protect environmental rights in Chongqing. By the time of the debate over the dams on the Nu River, a rather disorganised environmental network was starting to take shape.

Back then the Nu River debate and the State Environmental Protection Agency’s “environmental storm” crackdowns both highlighted a conflict between protecting the environment and economic development. What’s your view on that process?

I think the more important context for that time was the speeding up of the third round of industrialisation in 2002-2003, after WTO entry. Heavy and light industries sprang up everywhere, and just two or three years later there was growing awareness of the consequence of the blind pursuit of GDP growth. In some cases people were uneasy about the damage caused just by the construction work, before production even started.

Pan Yue, the deputy head of SEPA at the time, intervened in several cases, all during the development stage. From the controversy over the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) of engineering projects inside the Summer Palace, to the establishment of EIAs for strategic and regional planning, to the restrictions on project approvals in key areas, the central government had to go through a procedural tug of war with local governments over project development. And that lack of order laid the foundation for later over-capacity in steel and concrete production, and in coal-fired power.

The issues our team at Greenpeace worked on – the Sinar Mas Group deforestation in Yunnan, GM crops, electronic waste – weren’t the core environmental conflicts at the time. But they did reflect the landscape of that period of rapid economic growth: companies ignoring public oversight, the importing of some out-of-date industrial methods, local governments ignoring the law, dealings between officials and the rich. Many environmental and development issues came to public attention. But at the time, Greenpeace didn’t have a complete narrative to articulate these problems.

And despite those “environmental storms,” the later environmental degradation still happened.

In the end we still saw pollution, and of course one reason is that NGOs weren’t strong enough, but the main responsibility can’t lie with the people pointing out the problems. China was developing too quickly, too suddenly, and was too driven by economic growth. The government didn’t fully grasp this. It wasn’t until the Beijing smogs that we saw top Chinese officials change their understanding of development and the environment.

In 2008, Beijing hosted the Olympic Games, and the city’s environmental issues became an international topic. Greenpeace published a report at the time, titled Beyond Beijing, Beyond 2008. What did the Olympics mean for environmentalism in China?

I think 2008 was a watershed year, it was a year when China demonstrated its economic strength. And there was no way the Olympics could be held without discussing the environment, which was a matter of international concern at the time. That report looked at the problems with a growth-only model, and pointed out there was another, greener, route to development.

At the time, China wasn’t “green”. Although some green technology and measures were used in Olympic venues, as inspiration for the future, these weren’t the mainstream. But when we evaluate the environmental benefits of the 2008 Olympics, we shouldn’t just compare it with [other Olympic bidders] Vienna or Paris of the time. You need to look at how Beijing in 2008 had improved over Beijing in 2000. The population had doubled, the number of vehicles on the streets had tripled, so keeping air pollution at the same level would have been next to impossible. But I think reports like Beyond 2008 showed officialdom a new point of view: development can and should take place without an increased environmental footprint, and we should bring that about as soon as possible.

Later, in your role as an expert with the UN Environmental Programme, you took part in the environmental assessment for the Shanghai World Expo. Did that confirm your views?

The Beyond 2008 report accidentally landed us in the scenario where emerging economies such as China and the other BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) and MINT nations (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey) had to find some breakthrough in the relationship between the environment and development.

I went to visit coal-fired power plants in Shanghai as part of that assessment process, and had a number of discussions with colleagues from international NGOs. They were advocating a “No New Coal” approach globally, which I opposed. I thought that for developing nations that was unfair, unrealistic and illegitimate at that time, and taking that stance immediately disqualified you from discussing energy in China.

What I saw was that Shanghai had a de facto cap on coal-fired power. It never called it that, but the city encouraged renewables, and required all new coal power capacity to be replacements for older capacity. The new plants were more efficient and generated the same power with less coal. Shanghai was already trialling ultra-supercritical generators and had tough rules on scrubbing sulphur and nitrogen, which made coal power more expensive. I think for that point in time (around 2010) these were appropriate and progressive policies. If China as a whole had adopted those policies, we wouldn’t have seen such excessive expansion of coal power later. I think that was a more stable, realistic and fairer approach for a developing nation.

You later left international NGOs and joined SEE and founded the Greenovation Hub. Was that due to these ideas?

There was a link. I felt very strongly that the views coming from western environmental NGOs didn’t match the actual situation. They didn’t have a compelling argument for how emerging and developing nations could grow their economies while also protecting the environment.

When researching Shanghai’s waste policy, I found the city produced less waste per resident than the EU. The city government had already done a lot, but still had over 10,000 tonnes of waste to deal with every day. If you then sit opposite government officials and tell them they shouldn’t be building incinerators and landfill sites, they’ll think you’re being unrealistic. And that made me realise: we need to recognise that the mainstream stances of some western environmental NGOs don’t offer good answers to the actual problems these countries are facing.

I was very concerned at that point. I’d been working for international NGOs for 10 years, but I had a real longing to work closely with China’s grassroots NGOs. Our proposals had to be more localised, to be more convincing to the people who set policies, to be more realistic.

I moved to SEE after the World Expo job, because I wanted to see why entrepreneurs were concerned about the environment [SEE Conservation was founded by a group of Chinese entrepreneurs concerned with the environment]. What were they doing? What were they preparing to do? At the same time I became executive board chair of Friends of Nature. Meanwhile, some friends and I proposed the idea that “activists need to have a sense of agency” – they should look at the Chinese reality and look for appropriate stances and ways to engage, rather than reciting whatever some international organisation has written and translating it into Chinese.

And did things look different from that new viewpoint?

Once I got free of those restrictions, things looked much clearer. At that point the country’s top entrepreneurs were getting ready to work on environmental protection – so why weren’t China’s NGOs joining forces with them? I really liked what the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs did later, showing those entrepreneurs how they could use public pollution data to persuade businesses to make environmental improvements in the supply chain. Some of the SEE entrepreneurs were very concerned that their firms, or their suppliers, not appear on the IPE’s pollution maps, and that gave rise to the Green Supply Chains project. That interaction between IPE and SEE could be said to be the first time that China’s grassroots environmental forces joined up with influential decision-makers – and they were able to work together and achieve things.

As chair of Friends on Nature, I saw how it created the possibility of bringing environmental public interest lawsuits. And local groups, such as Chongqing Two Rivers, Green Kunming and Gansu Green Camel Bell, were at work too – all very small organisations, but full of ambition.

You just described the 2012 smogs as the point at which Chinese leaders changed how they viewed environment and development issues.

By the winter of 2012, the leadership would have seen very clearly that the business-as-usual development model was not sustainable. Something had to change. There was a clear change in language, with the “ecological civilisation” becoming a buzzphrase seen everywhere.

But if it hadn’t been for those quixotic efforts of green NGOs in the 2000s, those changes may have been less certain, or happened more slowly. Those organisations spent those years accumulating the power to build up the awareness and appropriate lexicon to mentally prepare the public for the environment and development debate. So when the opportunity for change arrived, everyone was able to recognise it and take advantage.

And what was behind your decision to go back to working for an international NGO in 2013, when you joined WWF?

I knew that WWF was looking for someone Chinese to head up development of the organisation. It was the largest international environmental NGO, and it wanted to localise, and that was a post where I could do some good. And looking back, that has been the case over these seven years. The WWF now is more localised and has a greater sense of agency.

In the past, money came from overseas, with other WWF offices funding on-the-ground projects in China directly and bypassing the Beijing office. We’ve just set up the Beijing office as an independent country office in the WWF network which can set its own policies and strategies, rather than acting as a branch of head office, and can place more emphasis on working within the reality in China. We’ve also had an internal reorganisation, and are fundraising in line with our own strategy.

Now we’re one of the most influential offices in WWF’s global network, and I think that’s a very important change. I think that reflects to some degree China’s increasing influence internationally, even though our budgets are much lower than other offices. I also contacted WWF offices in other developing countries and encouraged annual meetings on south–south cooperation. These are all things that have given me a strong sense of achievement.

During the 2010 Tianjin climate talks, you made a few observations and criticisms of Chinese environmental NGOs. What do you have to say to organisations about to participate in the talks on the UN Convention on Biological Diversity in Kunming?

I was an early advocate for the Civil Society Alliance for Biodiversity Conservation, so Chinese NGOs would participate in the conference in a more systematic and organised manner. I’m sure they will do better than in Tianjin. At the least, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment has invited NGOs to join the alliance – that’s not something you could have predicted a decade ago. That shows more trust and understanding between Chinese NGOs and the state.

I hope Chinese NGOs can mould some of the discussions on biodiversity, bringing in new points of view and the unique experience China has accumulated during its rapid development. What I particularly want to point out is that views in the west are still very dichotomic: the environment and the economy are in opposition, it’s a zero-sum game, if one benefits the other loses, and it’s best if nobody lives in protected areas. You still see these trends when major NGOs discuss the CBD targets. But we can’t protect half the planet and then leave the other half to be ruined.

Within the WWF, I’ve advocated for a New Deal for Nature and People. People have been living in protected areas in China since the WWF started working here four decades ago. There are plenty of locals even in the core panda reserves, their families have lived there for generations. In the Daoist tradition we have the idea of “grotto-heavens”, mountain and forest refuges away from the towns and cities – but these are still inhabited. For example, the Zhongnan Mountains outside Chang’an, Mount Qingcheng outside Chengdu, these are “grotto-heavens”. There were always clear understandings – no poisoning of water sources, no harming of wildlife, only careful use of fire. In terms of social function, this was a productive environment, but also a type of insurance – in times of war, people would flee to these refuges.

So these could be seen as the earliest form of protected area. And on this view, China’s protected areas have always been inseparable from people – people live there, they flee there. It’s like the yin-yang symbol, where each side contains the birth of the other.