In 1985, when Stephen DiRado was just a few years out of college, he bought his first large-format, 8x10 camera. Since each exposure cost eight bucks in today’s dollars, the process required contemplation; he couldn’t simply snap 100 images and pick out the handful he liked best. The stakes were high, but the payoff was immense: A well-executed photograph could contain enough rich detail to tell a whole story.

He was hooked. He would lug the 35-pound camera to places in Worcester, Massachusetts, like Bell Pond and the Worcester Center Galleria to photograph people whom, as he put it, “I had no business being with.” The neighborhood kids, cops, clerks, butchers and families who let DiRado into their worlds were generous enough to pose – and hold still – so he could make a photograph.

“I think I disarmed everybody with the huge camera,” he explained, “because there was nothing to conceal, nothing to hide.”

He was also constantly photographing his family and friends, who became so used to seeing the big box on a tripod during dinners and holiday gatherings that it became “almost invisible.”

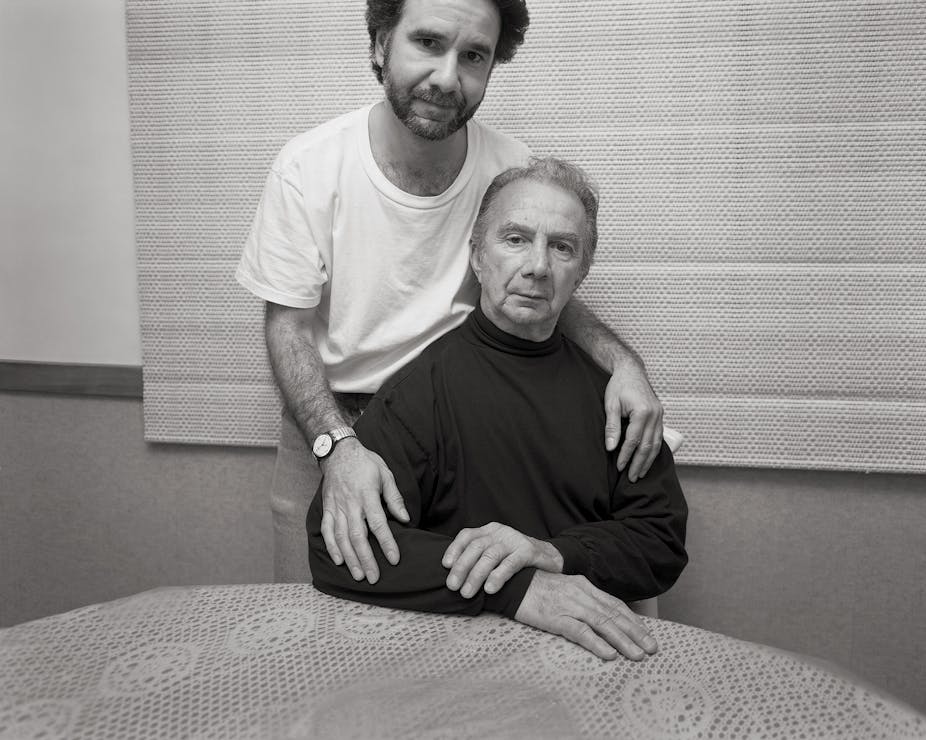

In 1993, DiRado noticed something didn’t seem quite right with his father, Gene, so he made an appointment to photograph him at his home in Marlborough, Massachusetts. It was the beginning of a 16-year project making photographs of his father, who was eventually diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. His book of the photographs, “With Dad,” was published in November 2019.

In an interview, which has been edited for length and clarity, Stephen DiRado describes the agony, anxiety and devotion he felt during those years. It was an entirely different kind of story and challenge: What do you do when the subject is a disease as much as a person, and when the disease then subsumes the person, to the point where he can’t remember his own son?

Yet Stephen continued to show up, camera in tow. Miraculously, the camera remained as strong a conduit from son to father as it had ever been, a channel forged from thousands of photographs taken over decades.

In the camera’s presence, even though Gene could no longer recognize Stephen, he knew enough to hold still.

In the early stages of your dad’s disease, what kind of stories did the photographs tell?

I grew up in a large Italian family that, at the drop of a pin, would get together. My mother always had extra plates at the dinner table. But when I was younger, I was very inhibited, while the rest of the family was so talkative. So I would just watch them and observe, and I started to understand more about body language. I was creating my own little stories about how what they were saying was not necessarily what their bodies were telling me.

Around the time my father was 57 or 58, I started noticing that something was off. He wasn’t as engaged anymore, and he started to isolate himself and sit in front of the TV, but not really watch.

That just didn’t seem like my father. So I started to make appointments to photograph him at his house in Marlborough, Massachusetts. I’d look through the photos wondering what was going on, what could be wrong.

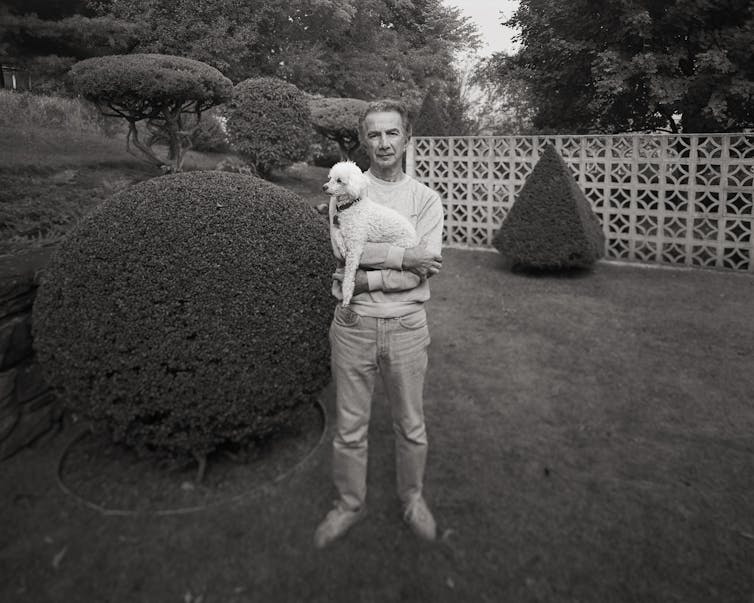

I thought one might hold the answer. It’s from 1993 and it’s in his backyard. I put him in the center of the photo, like a bull’s-eye, and he’s holding his all-time love, his dog, Missie. My father’s manicured, the dog’s manicured. Those are my father’s hedges and bushes, they’re manicured. It’s a pretty put together guy there. But there’s something about the look that was, for me, a little off. There’s something too manicured about it all. The surface is kind of fake. So I thought it must be depression.

When did the seriousness of the disease really start to hit home?

In 1998, he had a stroke. I went right to UMass Medical Center, and I stayed with him for the next three days, hanging out and photographing him. And at one point one of the nurses said, “I think your father has some form of dementia, and he might even have this thing called Alzheimer’s.”

So I remember saying to my father, “Dad, they say you might have this thing Alzheimer’s.” He said, “Well, how long do you think I’ll have it?” I said, “Dad, I don’t know. This is not good. But you can count to 10, right?” He said, “Of course I can count to 10.”

And he said, “One, two, three, four, five, six – oh I don’t want to do this.”

After the stroke, he was really starting to go downhill. He had a cognitive test and, sure enough, he flunked it. There was a high probability – but it wasn’t decisive – that he had Alzheimer’s.

My brother and sister and I decided that we would “daddy-sit” and take turns on weekends to give my mother some time off to go visit family or just get away. So one weekend in November 2003, it was my turn. I fed him dinner. We watched TV, and he sat there, in his pajamas, like he always did.

But I noticed that every hour or so, he’d get up and go into the bathroom. I started eavesdropping but didn’t hear anything.

An hour later, he’d return to the bathroom. I finally said, “I’m coming into the bathroom next time you go in there.” I followed him in and he walked up to the mirror, and he just stared at himself.

I thought that he must be holding on to himself, his sense of identity. So I said, “Dad, you know what? I’m gonna photograph you looking in the mirror.” I dropped the legs of the tripod and said, “Dad you know the deal, I’m gonna have to hit the flash off this ceiling, and I’m gonna photograph you inspecting yourself. You have to stay very still.”

The lens was cocked. I had the cable in my hand. “Here we go,” I said, “One, two –” and on “two” he turned and looked at the camera, and he smiled. I asked him what he was doing.

He said, “The man in the mirror is looking at you. And I want to look at you.”

This was so far beyond what I had ever imagined. I guess I had been in denial. I wondered whether I should stop the project right then and there.

I eventually said, “Dad, what do we think about the man in the mirror?”

“He’s a good man,” he said.

“I think he’s a great man,” I said, “and I think we both need to look at the man in the mirror and make this photograph.”

That sounds like a turning point – you were wondering whether you should stop the project. What were you afraid of and how did you push through?

The thing about any project – it doesn’t matter which one – is that great trepidation. Is the work soft? Am I being indulgent? Am I photographing my father for selfish reasons? That never went away.

And you know what? It is a very selfish thing. All art is selfish. Don’t let anybody fool you. I make photos and my art because I’m telling a story to the best of my ability, and I’ll do everything in my powers to make it very powerful with the material that I have. I need to seize the moment and mold it. This is being offered to me right now. I have to deal with it.

But at the same time, I’m also making art for 100 years from now – forget vanity, forget about privacy. This is so 100 years from now, historians, doctors, kids, artists, whoever can look at these images. And I hope by then, there is no more Alzheimer’s, that it will be like looking at leper colony photos.

Once your dad stopped being able to recognize you, how did he deal with the presence of this photographer and his camera?

I’ve been photographing my family since I was 12 years old. I photograph 24/7. If you’re a part of my life, if we were hanging out in a room together, I’d be photographing you.

By the time he went into the nursing home in July 2004, it was just the camera he recognized. To him, I was no longer existent. But he recognized the camera and knew enough to stay still. I think that this was one of the hard, ingrained things – tens of thousands of times being photographed by me, saying “hold still, hold still, hold still.”

How often did you photograph him once he was in the nursing home?

I went two or three times a week during a five-year period. Whenever I would get in my car to leave, I would get all nervous, even though I had been doing this forever. I’d start thinking about how I needed to make some kind of statement of value, and I’d get a stomach ache.

I’d be like, “Oh, you’re so full of s— DiRado, you go through this every friggin’ week. I’m so fed up with you. Get in that car right now.” And I would drive there feeling like I was gonna throw up, but the minute I touched the door to the nursing home, it all went away. I became my father’s son, a soldier intent on making the best possible art I could.

That’s another thing about the camera: When you carry 35 pounds over your shoulder to some destination, you’re going to make a photo. You’re going to make something.

And then, about once a week, after leaving, I would take a back road to Worcester so I could stop at Newbury Comics, where I would treat myself to a used video. After all, I had just been a good boy, right? We’re always our parents’ kids.

Towards the end, he looks so peaceful.

He slept often. It definitely brought me back to being 5 years old and sneaking into my parents’ bedroom and watching them sleep. These are very peaceful, quiet moments for any child who has done this.

He became a human still life. I would study his ears, his face. I could take the time to light him, to notice his hands, his fingernails growing out.

During the last six months of his life, something happened. It was like he found some level of spirituality or calmness. He was always surrounded by these stuffed animals and holding on to them. And he was always smiling. He was someplace else, between Earth and heaven.

Đăng nhận xét