Bao Yongqing is the winner of this year’s Wildlife Photographer of the Year award

With his image of a marmot being attacked by a Tibetan fox, Bao Yongqing has won the prestigious Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition.

Sir Michael Dixon, director of London’s Natural History Museum, which runs the competition, said the winning image “captures nature’s ultimate challenge – its battle for survival”.

Chair of the judging panel, Roz Kidman Cox, said: “Images from the Qinghai-Tibet plateau are rare enough, but to have captured such a powerful interaction between a Tibetan fox and a marmot – two species key to the ecology of this high-grassland region – is extraordinary.”

Bao Yongqing is a wildlife photographer from Qinghai province. He’s a trained ecologist and director of the Qilian Mountains Nature Conservation Association of China.

The Qinghai-Tibet plateau is an important source of fresh water for Asia and rich in biodiversity. But the region is particularly vulnerable to climate change resulting in the melting of snow and glaciers, deterioration of wetlands and loss of permafrost, putting pressure on habitats.

Another photograph of Qinghai-Tibet also picked up a prize in the competition. Fan Shangzhen’s image of a small herd of male chiru (Tibetan antelope) in the Altun Shan National Nature Reserve won in the “Animals in their environment” category.

Winners of the competition were announced on 15 October in London. Now in its 55th year, the competition received 48,000 entries from photographers across 100 countries. An exhibition at the Natural History Museum opens on 18 October and runs until the end of May 2020.

Sir Michael Dixon, director of London’s Natural History Museum, which runs the competition, said the winning image “captures nature’s ultimate challenge – its battle for survival”.

Chair of the judging panel, Roz Kidman Cox, said: “Images from the Qinghai-Tibet plateau are rare enough, but to have captured such a powerful interaction between a Tibetan fox and a marmot – two species key to the ecology of this high-grassland region – is extraordinary.”

Bao Yongqing is a wildlife photographer from Qinghai province. He’s a trained ecologist and director of the Qilian Mountains Nature Conservation Association of China.

The Qinghai-Tibet plateau is an important source of fresh water for Asia and rich in biodiversity. But the region is particularly vulnerable to climate change resulting in the melting of snow and glaciers, deterioration of wetlands and loss of permafrost, putting pressure on habitats.

Another photograph of Qinghai-Tibet also picked up a prize in the competition. Fan Shangzhen’s image of a small herd of male chiru (Tibetan antelope) in the Altun Shan National Nature Reserve won in the “Animals in their environment” category.

Winners of the competition were announced on 15 October in London. Now in its 55th year, the competition received 48,000 entries from photographers across 100 countries. An exhibition at the Natural History Museum opens on 18 October and runs until the end of May 2020.

Image © Bao Yongqing (China) / Wildlife Photographer of the Year Grand title winner 2019

It was early spring and very cold on the alpine meadowland of the Qinghai-Tibet plateau in China’s Qilian Mountains National Nature Reserve. The marmot was hungry. It was still in its winter coat and not long out of its six-month hibernation deep underground with the rest of its colony of 30 or so. The marmot had ventured out of its burrow to search for plants to graze on when the fox rushed forward, her long canines revealed. Such predator‑prey interaction is part of the natural ecology of the plateau ecosystem, where rodents, in particular the plateau pikas (smaller than marmots) are keystone species.

It was early spring and very cold on the alpine meadowland of the Qinghai-Tibet plateau in China’s Qilian Mountains National Nature Reserve. The marmot was hungry. It was still in its winter coat and not long out of its six-month hibernation deep underground with the rest of its colony of 30 or so. The marmot had ventured out of its burrow to search for plants to graze on when the fox rushed forward, her long canines revealed. Such predator‑prey interaction is part of the natural ecology of the plateau ecosystem, where rodents, in particular the plateau pikas (smaller than marmots) are keystone species.

Image © Riccardo Marchgiani (Italy) / Wildlife Photographer of the Year Winner 2019, 15-17 years old

Geladas are a grass‑eating primate found only on the Ethiopian plateau. At night, they take refuge on steep cliff faces, huddling together on sleeping ledges. They emerge at dawn to graze on the alpine grassland.

Geladas are a grass‑eating primate found only on the Ethiopian plateau. At night, they take refuge on steep cliff faces, huddling together on sleeping ledges. They emerge at dawn to graze on the alpine grassland.

Image © Fan Shangzhen (China) / Wildlife Photographer of the Year Winner 2019, Animals in their environment

A small herd of male chiru leaves a trail of footprints on a snow-veiled slope in the Kumukuli desert of China’s Altun Shan National Nature Reserve. These nimble antelopes – the males with long, slender, black horns – are high-altitude specialists found only on the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. A million chiru once ranged across this vast plateau, but commercial hunting in the 1980s and 1990s left only about 70,000 individuals. Rigorous protection has seen a small increase, but demand, mainly from the West, for shahtoosh shawls still exists.

A small herd of male chiru leaves a trail of footprints on a snow-veiled slope in the Kumukuli desert of China’s Altun Shan National Nature Reserve. These nimble antelopes – the males with long, slender, black horns – are high-altitude specialists found only on the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. A million chiru once ranged across this vast plateau, but commercial hunting in the 1980s and 1990s left only about 70,000 individuals. Rigorous protection has seen a small increase, but demand, mainly from the West, for shahtoosh shawls still exists.

Image © Audun Rikardsen (Norway) / Wildlife Photographer of the Year Winner 2019, Behaviour: birds

Golden eagles need large territories, which most often are in open, mountainous areas inland. But in northern Norway, they can be found by the coast, even in the same area as sea eagles. They hunt and scavenge a variety of prey, from fish, amphibians and insects to birds and small and medium-sized mammals such as foxes and fawns.

Golden eagles need large territories, which most often are in open, mountainous areas inland. But in northern Norway, they can be found by the coast, even in the same area as sea eagles. They hunt and scavenge a variety of prey, from fish, amphibians and insects to birds and small and medium-sized mammals such as foxes and fawns.

Image © Zorica Kovacevic (Serbia/US) / Wildlife Photographer of the Year Winner 2019, Plants and fungi

Festooned with bulging orange velvet and trimmed with grey lace, the arms of a Monterey cypress tree weave an otherworldly canopy over Pinnacle Point, in Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, California, US. This tiny, protected coastal zone is the only place in the world where natural conditions combine to conjure this magical scene. The spongy orange cladding is a mass of green algae spectacularly coloured by carotenoid pigments, which depend on the Monterey cypress for physical support but photosynthesize their own food. The vibrant orange is set off by the tangles of grey lace lichen (a combination of alga and fungus), also harmless to the trees.

Festooned with bulging orange velvet and trimmed with grey lace, the arms of a Monterey cypress tree weave an otherworldly canopy over Pinnacle Point, in Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, California, US. This tiny, protected coastal zone is the only place in the world where natural conditions combine to conjure this magical scene. The spongy orange cladding is a mass of green algae spectacularly coloured by carotenoid pigments, which depend on the Monterey cypress for physical support but photosynthesize their own food. The vibrant orange is set off by the tangles of grey lace lichen (a combination of alga and fungus), also harmless to the trees.

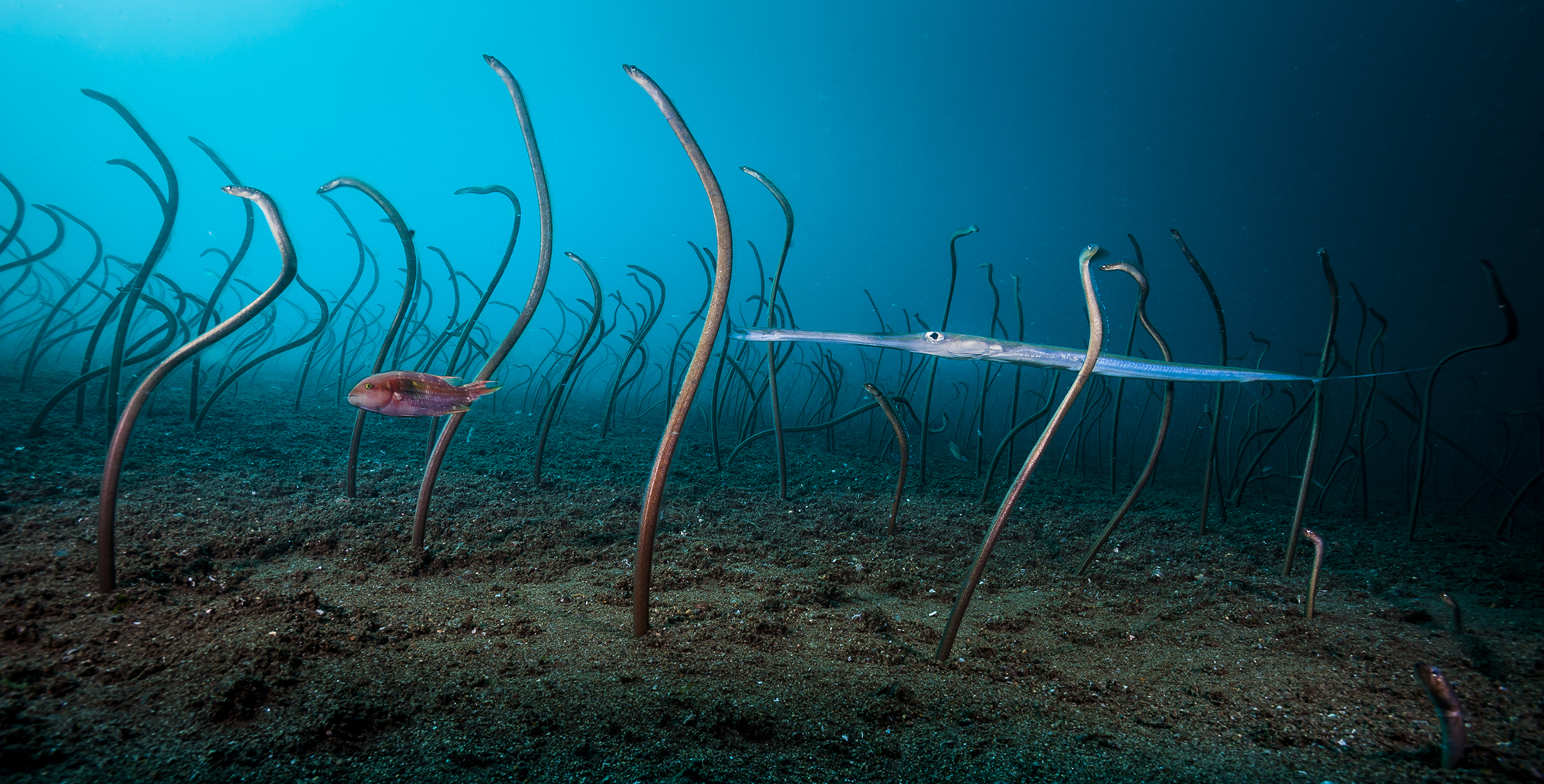

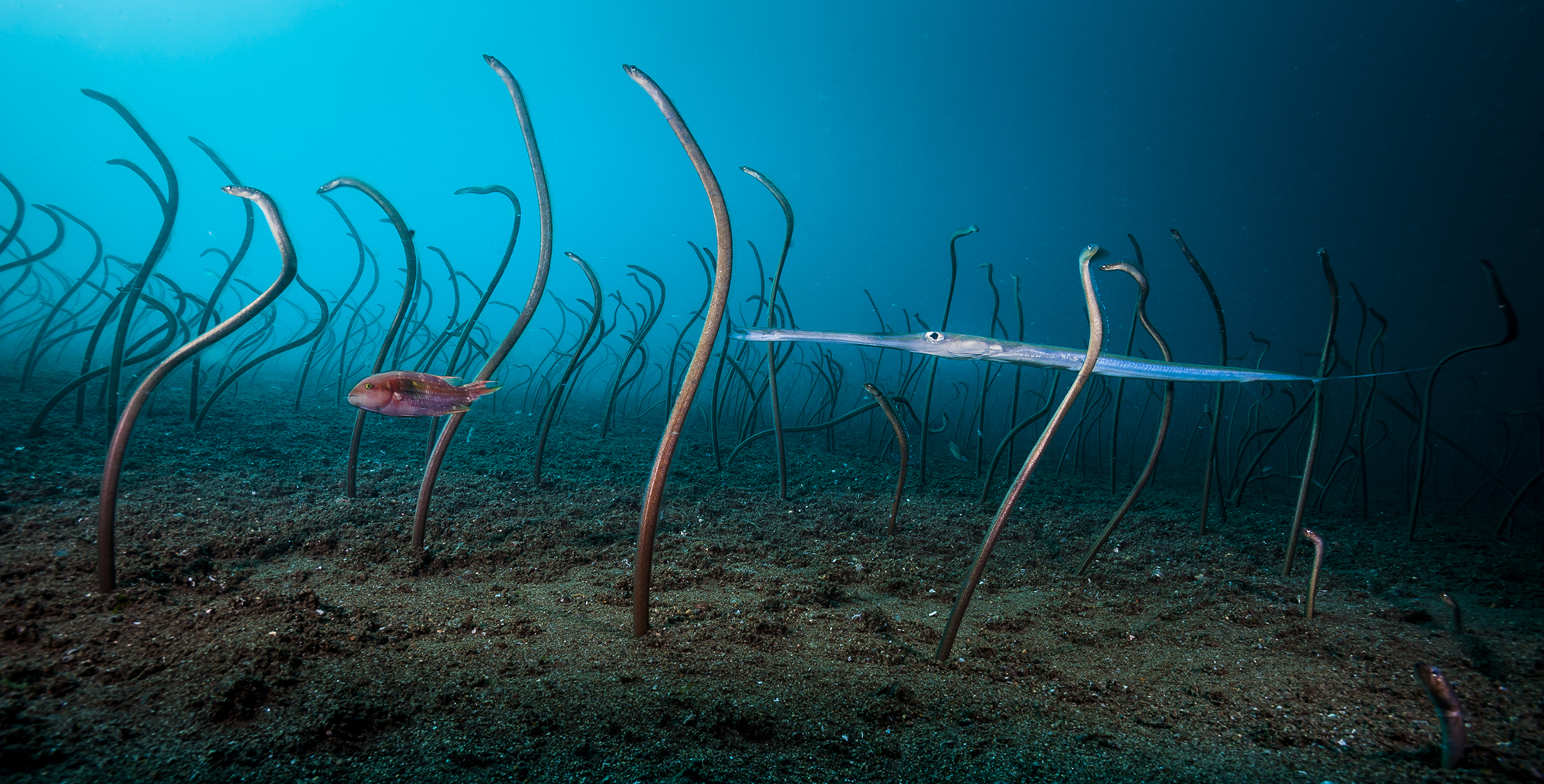

Image © David Doubilet (US) / Wildlife Photographer of the Year Winner 2019, Under water

The colony of garden eels was at least two thirds the size of a football field, stretching down a steep sandy slope off Dauin in the Philippines – a cornerstone of the famous Coral Triangle. These warm-water relatives of conger eels are extremely shy, vanishing into their sandy burrows the moment they sense anything unfamiliar.

The colony of garden eels was at least two thirds the size of a football field, stretching down a steep sandy slope off Dauin in the Philippines – a cornerstone of the famous Coral Triangle. These warm-water relatives of conger eels are extremely shy, vanishing into their sandy burrows the moment they sense anything unfamiliar.

Image © Charlie Hamilton James (UK) / Wildlife Photographer of the Year Winne 2019, Urban wildlife

On Pearl Street in New York’s Lower Manhattan, brown rats scamper between their home under a tree grille and a pile of garbage bags full of food waste. Their ancestors hailed from the Asian steppes, travelling with traders to Europe and later crossing the Atlantic.

On Pearl Street in New York’s Lower Manhattan, brown rats scamper between their home under a tree grille and a pile of garbage bags full of food waste. Their ancestors hailed from the Asian steppes, travelling with traders to Europe and later crossing the Atlantic.

Image © Max Waugh (US) / Wildlife Photographer of the

Year Winner 2019, Black and white

In a winter whiteout in Yellowstone National Park, a lone American bison stands weathering the silent snow storm. Bison survive in Yellowstone’s harsh winter months by feeding on grasses and sedges beneath the snow. Swinging their huge heads from side to side, using powerful neck muscles – visible as their distinctive humps – they sweep aside the snow to get to the forage below.

In a winter whiteout in Yellowstone National Park, a lone American bison stands weathering the silent snow storm. Bison survive in Yellowstone’s harsh winter months by feeding on grasses and sedges beneath the snow. Swinging their huge heads from side to side, using powerful neck muscles – visible as their distinctive humps – they sweep aside the snow to get to the forage below.

Image © Alejandro Prieto (Mexico) / Wildlife Photographer of the Year Winner 2019, Wildlife photojournalism: single image

Under a luminous star-studded Arizona sky, an enormous image of a male jaguar is projected onto a section of the US-Mexico border fence. Today, the jaguar’s stronghold is in the Amazon, but historically, the range of this large, powerful cat included the southwestern US. Over the past century, human impact – from hunting, which was banned in 1997 when jaguars became a protected species, to habitat destruction – has resulted in the species becoming virtually extinct in the US.

Under a luminous star-studded Arizona sky, an enormous image of a male jaguar is projected onto a section of the US-Mexico border fence. Today, the jaguar’s stronghold is in the Amazon, but historically, the range of this large, powerful cat included the southwestern US. Over the past century, human impact – from hunting, which was banned in 1997 when jaguars became a protected species, to habitat destruction – has resulted in the species becoming virtually extinct in the US.

Image © Stefan Christmann (Germany) / Wildlife Photographer of the Year Winner 2019, Wildlife photographer portfolio award

More than 5,000 male emperor penguins huddle against the wind and late winter cold on the sea ice of Antarctica’s Atka Bay, in front of the Ekström Ice Shelf. Each paired male bears a precious cargo on his feet – a single egg – tucked under a fold of skin (the brood pouch) as he faces the harshest winter on Earth, with temperatures that fall below -40C, severe wind chill and intense blizzards. The females entrust their eggs to their mates to incubate and then head for the sea, where they feed for up to three months.

More than 5,000 male emperor penguins huddle against the wind and late winter cold on the sea ice of Antarctica’s Atka Bay, in front of the Ekström Ice Shelf. Each paired male bears a precious cargo on his feet – a single egg – tucked under a fold of skin (the brood pouch) as he faces the harshest winter on Earth, with temperatures that fall below -40C, severe wind chill and intense blizzards. The females entrust their eggs to their mates to incubate and then head for the sea, where they feed for up to three months.

Now more than ever…

chinadialogue is at the heart of the battle for truth on climate change and its challenges at this critical time.

Our readers are valued by us and now, for the first time, we are asking for your support to help maintain the rigorous, honest reporting and analysis on climate change that you value in a 'post-truth' era.

Support chinadialogue

Đăng nhận xét