|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Want to change how you receive these emails?

You can update your preferences or unsubscribe from this list.

Purpose of the articles posted in the blog is to share knowledge and occurring events for ecology and biodiversity conservation and protection whereas biology will be human’s security. Remember, these are meant to be conversation starters, not mere broadcasts :) so I kindly request and would vastly prefer that you share your comments and thoughts on the blog-version of this Focus on Arts and Ecology (all its past + present + future).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The big environmental stories in the Chinese media (22-28 October)

The assertion that the Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla) is “functionally extinct” has stirred up a new round of fierce criticism this week.

At a conference in Nanjing on Monday (25 October), the China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation (CBCDGF) repeated the claim it had first made in 2019. Li Binbin, a conservation scientist at Duke Kunshan University, responded that no peer-reviewed scientific study has reached such a conclusion. “Advocacy cannot be based on false and misleading information,” she later wrote on Weibo. “Please do not destroy public trust in conservation efforts.”

Li’s criticism echoed through the conservation community. Many agreed that the Chinese pangolin is critically endangered but that declaring it extinct is irresponsible. Gu Yourong, a Capital Normal University professor, wrote that such a declaration requires careful and extensive monitoring and research.

Some observers question CBCDGF’s motives for the claim. The foundation has been campaigning in recent years for the introduction of Malayan pangolins (Manis javanica) to the Chinese wild, on the premise that the Chinese pangolin is extinct. The Malayan pangolin is considered alien to most parts of China.

CBCDGF responded on Weibo that its declaration has promoted pangolin conservation in China, ramping up urgency and prompting the state to elevate the species from Class II to Class I protections. It also suggested critics are either “misinformed” or “have interest groups behind them.”

(Sources: China Dialogue)

The big environmental stories in the Chinese media (22-28 October)

China’s route to peaking emissions by 2030 and reaching carbon neutrality by 2060 has been sketched out in two documents released this week in the run up to COP26 in Glasgow. Part of the “1+N” policy package, the documents will form the backbone for more detailed upcoming policy on achieving the carbon goals.

On Sunday (24 October), the State Council issued its “Working Guidance for Carbon Dioxide Peaking and Carbon Neutrality”. This is the master document for future climate policy making – the “1” in the “1+N” – issued from the highest level of government. The most eye-catching target is to ensure “at least 80%” of energy consumption is from non-fossil fuels by 2060, though this figure had been used last year in modelling by Tsinghua University. Other than that, the guidance reaffirms key targets such as 25% non-fossil fuel energy consumption by 2030 and a 65% decline in energy consumption per unit of GDP by 2030 compared with 2005 levels.

The second document, “Action Plan for Carbon Dioxide Peaking Before 2030”, was released on Tuesday (26 October). This document again confirms previously announced targets rather than revealing new ones. It is understood to be one of an unspecified number of “N” documents that will be released to flesh out the decarbonisation policy roadmap in different sectors. The action plan includes a target of 20% non-fossil energy consumption by 2025, including by installing 80 GW of new hydropower between 2021 and 2030. The non-fossil energy targets also include installing 1,200 GW of wind and solar by 2030. Some commentators saw this as conservative given the scale of China’s wind and solar expansion in recent years.

The climate community now awaits China’s updated Nationally Determined Contribution to reducing emissions, which is expected to be released before COP26 begins on Sunday.

(Sources: China Dialogue)

China’s new stance against supporting coal abroad can move Cambodia towards a clean energy future, writes Bridget McIntosh of EnergyLab Cambodia.

By Bridget McIntosh, October 27, 2021

Over half of Cambodia’s electricity is generated in coal power plants, almost all built with Chinese involvement. Coal’s share in the energy mix was set to increase to three-quarters by 2030. Then came President Xi Jinping’s September announcement that China “will not build new coal-fired power projects abroad” and will step up support for green energy. The new stance may help Cambodia transition toward a more reliable and affordable electricity system, at a time when the country needs a green economic boost given Covid-19. It can also help Cambodia retain its largest industry, garments and footwear. Major international brands operating in the country have made requests for a cleaner energy grid.

Cambodia’s power system has proven highly adaptable over the past 20 years. At the turn of the century, only 17% of the population had access to the grid, and the system was three-quarters powered by fuel oil. By 2014, this had switched to nearly two-thirds hydropower, all of it built with Chinese involvement. Seven years later, Cambodia has a remarkably improved electrification rate of 93% and is in the middle of another transition, with over half of its power now coming from fossil fuels. Plans approved after power shortages in 2019 catalysed a return to fossil fuels, which were expected to supply 75% of power by 2030.

That was the plan at least. Now Cambodia may need to adapt again: depending on how Xi’s announcement plays out in practice, planned projects may be at risk. Our analysis shows Cambodia’s coal power capacity is projected to reach 4,675 megawatts (MW) within the next 10 years. Of that, only 675 MW is operational, and over 900 MW is under construction. The remaining 3,100 MW, two-thirds of the planned capacity, may be at risk, including the 2,400 MW which is supposed to be imported from projects planned in neighbouring Laos.

China’s announcement was well received around the world. It came amid a global energy crisis, with gas and coal prices soaring. Europe, for example, is having difficulty securing energy supplies for heating and electricity at the expected prices. The International Energy Agency (IEA) has pointed to insufficient investment in renewable energy, stating that US$4 trillion is needed by 2030, in order to remain on track for the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C warming limit. Increased financing and capacity would also help alleviate supply crunches.

What does this mean for Cambodia’s ability to create a secure, reliable and affordable power system? A great deal, actually. Cambodia has the opportunity to support much-needed investment to grow green out of the pandemic, to create jobs, lower electricity costs, and to improve the independence and supply security of its energy.

Concerning security, Cambodia’s current power plan needs huge imports of fuel and electricity, exposing it to a variety of geopolitical risks. Cambodia’s coal power fleet depends on imports, with power purchase agreements linked to the price of imported coal. This means its utility supplier, Électricité du Cambodge (EDC), has to pay more when global coal prices are high. In the last 18 months, prices have dived and soared, reaching both the lowest and highest they’ve been for 15 years. And gas prices are 10 times the level they were a year ago.

Can Cambodia have an affordable power supply without proceeding with its 3,100 MW of unbuilt coal projects? Thanks to the ever-dropping prices of renewables, the answer is yes.

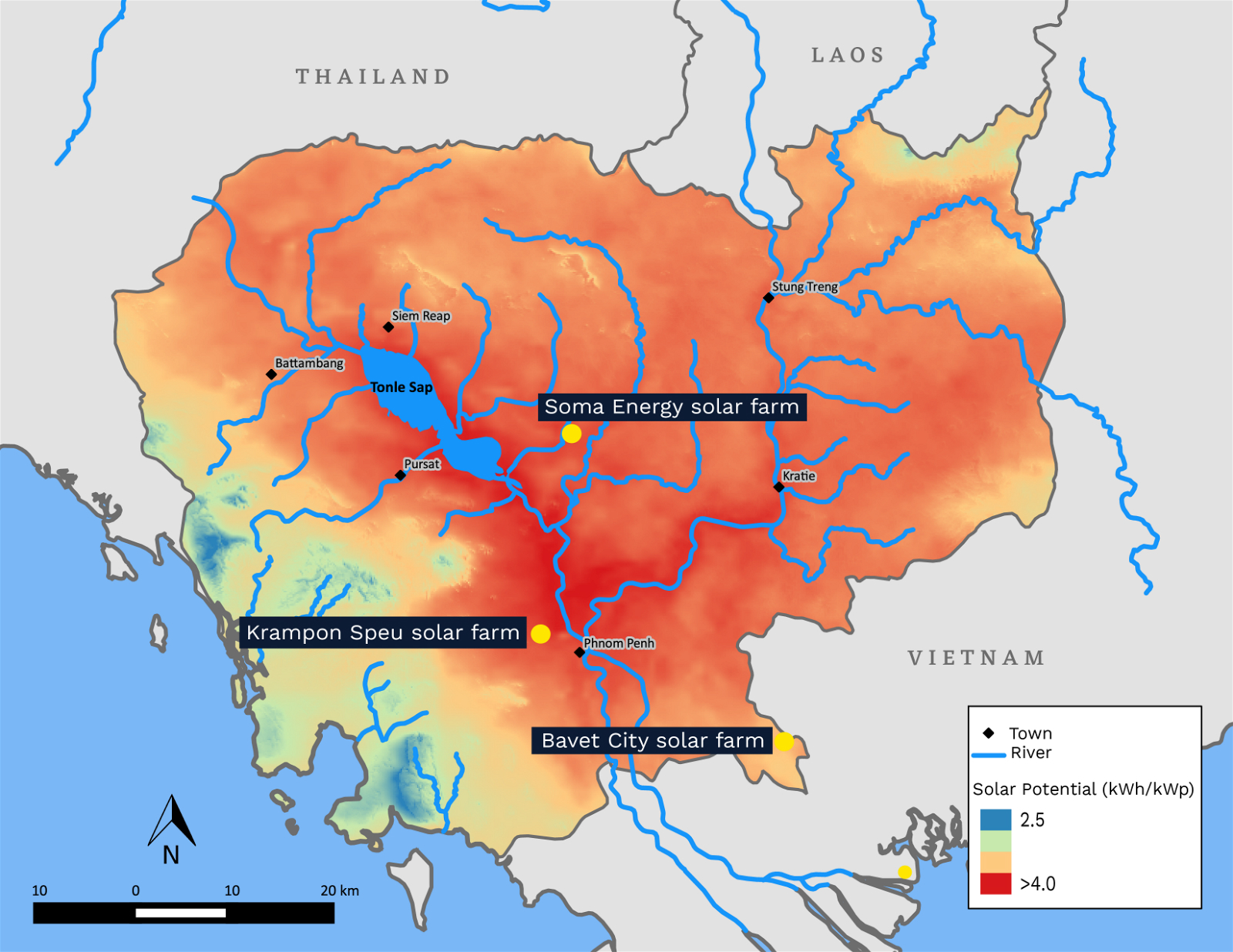

In Cambodia, solar and wind power are the cheapest source of new power supply, with sale prices to EDC between 3.9–6.9 cents per kilowatt hour (kWh), well below the proposed coal-power purchase price of 7.7 cents per kWh for the 2,400 MW Lamam and Xekong thermal power plants. Analysis for the Ministry of Mines and Energy’s renewable energy working group, seen by EnergyLab Cambodia and updated after President Xi’s coal announcement and the global energy crisis, shows that replacing this unbuilt coal power with solar, wind and some non-mainstream hydropower, as well as fast-responding battery storage and gas engine plants, would actually lower electricity system costs for Cambodia and ensure reliability.

Gas turbine plants are built to optimise fuel efficiency. They use closed-cycle turbines that run optimally at full output.

Gas engine plants, which operate through expansion or combustion of gas, have lower fuel efficiency and emit more pollutants. But with their rapid response and lower capital cost, they can work better in a system that needs to balance solar and wind.

If Cambodia’s electricity system takes on more solar and wind power because they are cheaper, is it possible for the country to secure a reliable system with power plants that depend on the weather? Again, yes. This is supported by modelling done by the renewable energy working group, which was referred to by the Australian ambassador to Cambodia at this year’s Cambodia Climate Change Summit.

The traditional idea of having big fossil-fuelled power stations producing constant baseload power output has been turned on its head. Now, everything should be done to bring in low-cost solar and wind, balancing out its variability with flexible, dispatchable power and using widely available weather and power forecasting technology. Flexible and dispatchable power comes from sources such as batteries, hydro storage and fast-responding gas engine plants, and through flexible demand management. By contrast, coal plants are not flexible at ramping up or down, or responding quickly to system changes.

New gas power projects must be designed for energy and system balancing only, and not for high-output baseload power; this balancing is where the quicker response available from a gas engine plant will be important. In Cambodia’s system, balancing is needed for hydro seasonality and lower solar output as the sun sets.

Diversity of the system will be key over the next 10 and 20 years. Cambodia can replace the unbuilt, unfinanced coal plants with a combination of solar, wind, hydro, gas engine plants and storage to maintain the same level of renewables share it has now – half. The planned 2,400 MW of coal projects in Lao PDR dedicated for supplying Cambodia can be replaced by domestic investment, saving US$16.4 billion in power import costs up to 2040; an estimated investment of US$6.8 billion could fund the creation of 10 gigawatts (GW) of solar and 1.5 GW of wind power capacity.

Higher shares of renewable energy will support global industries investing and operating in Cambodia who are under pressure to decarbonise their supply chains. Last year, major international clothing brands in Cambodia such as H&M, Puma, Adidas, Nike and Gap requested a higher share of renewables in the energy mix. They have made global renewable and climate commitments to their customers and they remain alarmed by the plans to further carbonise Cambodia’s grid. The garment and footwear sector represents over 800,000 jobs and around US$8 billion in annual export revenue.

Cambodia can have a cheaper, more reliable and more secure power system with less coal. It is imperative that planning and investment start as soon as possible. Chinese companies and investors are involved in almost all of Cambodia’s 410 MW solar power projects in the country, and they are now exploring wind power. They are also global leaders in battery storage.

China’s Eximbank has invested extensively in Cambodia’s transmission grid infrastructure. As countries like Vietnam, Canada and Australia have been learning, grid infrastructure planning for more solar and wind is essential. These countries were slow to develop transmission lines to bring low-cost solar and wind to demand centres, often resulting in wasteful “spilling” of renewable electricity. Planning for rooftop solar, consumed onsite at factories, can also help with transmission and distribution costs.

In his announcement against building new coal projects abroad, Xi also said “China will step up support for other developing countries in developing green and low-carbon energy”. A move away from coal towards a higher share of renewables could see Cambodia become a major beneficiary of Chinese investment and expertise in green energy for years to come. With the China–Cambodia free trade agreement ratified by the Cambodian National Assembly last month, and an updated investment law prioritising incentives for green energy, it looks like the future of Cambodia’s electricity system could be getting brighter – and greener.

Bridget McIntosh is an environmental engineer and country director of EnergyLab Cambodia, an organisation established to support the growth of the clean energy market in Cambodia.

(Sources: China Dialogue)

As COP26 approaches, the ADB is pitching a solution to help countries retire polluting coal plants early.

By Lou Del Bello, October 25, 2021

Mounting evidence from across the globe shows that coal has had its time. The most polluting fossil fuel is not only bad for the climate and public health, but it is also becoming financially unviable as renewable energy prices plummet. And yet, together with oil, it still dominates the world’s energy mix. Coal continues to play a major role in energy production and remains a major energy source in many Asian countries like China, India and Indonesia, as well as in many other parts of the world.

Now, a range of financial institutions in Asia and beyond are looking to buy out coal assets to hasten its phaseout. But experts still question whether the idea has what it takes to catalyse a deep and just energy transition.

In the latest report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), scientists have made clear once again that a deep decarbonisation of the world’s economy is essential to avoid the worst consequences of global warming. But markets alone do not seem to be able to displace coal fast enough.

“There is a general narrative that the transition beyond coal is inevitable, and that it’s only a matter of time,” says Justin Guay, director of global climate strategy at the Sunrise Project, a social enterprise. “But that’s only partially true.” Building new clean energy infrastructure is already cheaper than operating any old coal-fired power plant, he explains, so at least on paper there should be virtually no hurdles to a fast energy transition from fossil fuels.

However, “the reality is obviously much murkier, and much more difficult,” says Guay. All the economic pressures that would otherwise force coal plants to shut down because they are haemorrhaging money, he says, “don’t matter when you receive public subsidies in a variety of forms”.

According to the think tank Carbon Tracker Initiative, nearly 70% of the global coal fleet relies on what experts call market distortions, or policy decisions that help coal producers beat the competition.

Market distortions are unique to each country, explains Durand D’Souza, data scientist at Carbon Tracker Initiative. For example, in India, long-term contracts bind energy distributors to coal producers, even if their energy becomes expensive, passing the costs on to the consumer or other actors in the supply chain. In China, “GDP targets were incentivised over keeping electricity prices down,” he explains, “and coal plants have been, for a long time, an easy route to raise GDP quickly through investment”.

Guay believes that despite the current market distortions, regulators and utilities will eventually realise that coal is a bad investment. “But the only variable that matters is time, we actually need to accelerate [the transition] dramatically,” he says.

To do so, stopping the construction of new coal facilities is not enough. Instead, experts are suggesting that existing plants should be retired before completing their life cycle. In the US, the environmental organisation Sierra Club has been running a successful campaign for coal retirement across the country. The campaign has secured the retirement of 347 coal power plants across the country through advocacy and political pressure, with 183 left to target.

But phasing out coal in developing nations poses its own unique challenges, because communities are poorer and thus less able to adapt to change.

To facilitate a rapid but just transition from the fossil fuel, some financial institutions and research organisations have been exploring various ways to help coal-dependent developing nations decarbonise. Energy transition mechanisms (ETM) are one financial instrument designed to enable nations to retire their coal assets early. They involve public and private actors working together with governments to assess specific economic and regulatory risks and deploy the right set of incentives to decommission or repurpose coal plants.

At COP26, the Manila-based Asian Development Bank (ADB) will introduce a plan it has designed in partnership with the UK insurer Prudential to identify a portfolio of coal power plants to buy and retire across Southeast Asia, with an initial budget of US$4.05 million for the design phase.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is one of a group of financial institutions known as Multilateral Development Banks set up as regional arms of the World Bank.

Established in 1966, the ADB focuses on countries in the Asia-Pacific region. It currently has 68 member countries, of which 49 are in the region.

The ADB provides loans, technical assistance, grants and equity investments.

“ADB is finalising a pre-feasibility study – consisting of initial system-level analysis, plant-level modelling, and regulatory and policy review – in Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam,” a spokesperson said. This will be followed by an in-depth feasibility analysis focused on Indonesia and the Philippines.

According to the think tank Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), which has recently published an analysis of the ADB’s initiative, COP26 is particularly significant because it is “finally driving a new round of policy work by the [multilateral development banks], and ADB is running hard to have a compelling solution on the table for donor nations to support”. The ADB, the analysts say, has an important role to play because donor nations have struggled to find fundable initiatives in markets such as the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia and Bangladesh, where the energy sector is growing fast.

Buying out coal plants may be a straightforward idea, but in practice it is a task fraught with complexities. Melissa Brown, a specialist in Asian energy finance with IEEFA and an author of the report, explains: “We know that these types of proposals are most likely to succeed in markets that […] are subject to competition,” and that could be a problem for the ADB. “In Indonesia, in Vietnam, the vast majority of the power capacity is controlled by vertically integrated state-owned enterprises,” that control the entire supply chain. This means it will be hard to target players who may own old, high-emissions systems that are beginning to fear the competition and worry they may run out of business, she says.

Others believe that the astronomical cost of scaling up retirement of this fossil fuel is not worth it. Funding the buyout of one large coal-fired plant with a capacity of around 1 GW would cost $1 billion. To retire half of the coal fleet in Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam, the facility would need between $30 and 55 billion.

“For a billion dollars you can fund 2 GW of solar,” says Alexander Hogeveen Rutter, an energy storage finance specialist with the International Finance Corporation, a part of the World Bank group. “And even if you were to retire those assets currently operating at a low capacity, countries would just ramp up the capacity factor of the rest of the coal fleet,” he adds. “Any money you have should be invested in renewables and new storage first, and only after you have met the expected demand growth can you start retiring coal plants.”

In some countries, the costs of buying up coal plants could be partially offset by repurposing the plant into a solar plus battery system, which captures solar energy and stores it to be distributed at any time of the day, even when the sun doesn’t shine. In India, IEEFA found that the economic benefits of this switch would outweigh the cost of decommissioning fivefold. However, according to Rohit Chandra, energy and infrastructure expert and assistant professor at IIT Delhi’s School of public policy, there is still a long way to go for the idea to take root in India, the world’s fourth-largest global emitter after China, the US and the EU.

“If you start talking with banks, distribution companies, power generators and other stakeholders, in three to five years the idea may be taken seriously by the system,” he says. “But right now, the optics of it is that you want to pay us a lot of money to shut down our coal plants, at a time when we have record coal demand,” he explains. “Why would we want to shut down these assets when we need them the most?” Chandra says that not enough effort has been put into mainstreaming the idea of early coal retirement in India, and that this would be the first step required to make it work.

Ultimately, experts agree that there isn’t a one size fits all solution to retiring coal early. The real challenge to scaling up early coal retirement will be to get governments and the private sector on board with the idea, and to design models that work for each country’s unique power system and local communities, says the Sunrise Project’s Justin Guay.

A deal that does nothing for the coal-dependent communities that risk being pushed out of the workforce “is simply not tenable […] It would be disastrous to structure a coal buyout deal that benefits the utility and the investors and does nothing for the local communities or workers,” he says. For example, nearly half a million people in India currently work in the coal sector, one of the reasons why the government is finding it particularly hard to negotiate its exit.

The idea of paying off coal stakeholders, Guay adds, is a “bitter pill” that nobody will be willing to swallow, despite its potential climate gains, if the deal doesn’t offer a clear plan of how the communities will be involved in the process Depending on how it is structured, he says, if the transaction generates a return, a fair share needs to be siphoned off and put into new clean energy development, fossil fuel worker retraining and community transition. “And that is absolutely doable if the public is in the driver’s seat.”

Lou writes Lights On, a weekly newsletter tracking the climate, energy and business debate. She has been environment correspondent for Bloomberg in Delhi and a freelance science writer for BBC, Undark, Nature News, New Scientist and more

(Sources: China Dialogue)

New studies claim the young multilateral bank has loopholes in its environmental and social safeguards that allow negative impacts on communities.

By Shi Yi, Wawa Wang, October 26, 2021

The Beijing-based Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) will hold its sixth annual meeting virtually on October 26–28, a few days before UN climate talks kick off in Glasgow.

Many believe that multilateral financial institutions such as the AIIB play a vital role in developing better environmental, social and governance standards as the world strives to achieve a green recovery from the pandemic and avoid catastrophic climate change. This is a topic the AIIB plans to discuss on the first day of the annual meeting. Meanwhile, after three years of use, the bank has amended its Environmental and Social Framework (ESF), with a new version having gone into effect this month.

Recent investigations and studies, however, have called into question the impact of the AIIB’s investments and whether they are in line with its core values. Many civil society groups worry the bank’s ESF, along with other policies, lacked substantive commitments and clear criteria when first adopted in 2016, and that the new one has not fixed those issues.

At the beginning of this year, when celebrating its fifth anniversary as the youngest multilateral development bank, the president of the bank, Jin Liqun, addressed the idea of building green infrastructure to help countries achieve economic transition and carbon neutrality. Green means “not leaving a footprint on the environment and society,” he said.

Back in 2018, the AIIB approved a loan for tourism development on Lombok Island, across the sea from the world-famous island of Bali. The project is part of Indonesia’s plan to build 10 Bali-like tourist attractions. To many observers, the Lombok tourism and development project, which the AIIB categorised as “A” for environmental and social risks – meaning the riskiest – is an example of the bank’s challenge to assess resettlement action plans prepared by its clients.

The project was green-lighted during a wave of compulsory, violent displacement that began in 2018, months before the project’s approval. Investigations undertaken by NGOs in three consecutive years since 2019 have documented families that have lost livelihoods and income, forcing them to take young children out of school. Two villages, including indigenous communities, still dwell in temporary shelters two years after being removed from their homes without consent.

A joint study by the Heinrich Böll Foundation and Just Finance International examined how AIIB’s new green-lighted ESF measures would reduce transparency and accountability. For example, upon the bank’s adoption of the Policy on Public Information in 2018, the AIIB president said: “Transparency and accountability are the two main pillars of AIIB’s governance”. Still, the framework has many exemptions where the list of documents and timebound requirements are not applied. Further, ESF provisions allow the AIIB to delegate disclosure responsibility to its clients in some circumstances. Loopholes in the policy override the stated intention of maximum transparency, the report says.

For many multilateral development banks, such environmental and social harms caused by the Lombok project would have triggered a public evaluation. The AIIB’s response is seen as insufficient. While the bank’s environmental and social due diligence team has written about “applying best environmental and social practices in projects”, it has not disclosed monitoring or investigation reports that respond substantively to those concerns.

Another report published by Recourse and Urgewald reviewed the AIIB’s accountability mechanism before its annual meeting. Despite 142 projects approved and over US$28 billion invested in its six years of operation, the bank has yet to receive a single complaint.

The study believes that one of the main reasons is more than half of the projects, 72 out of 142, are not eligible for its accountability mechanism. Under the AIIB’s rules, projects co-financed with other multilateral development banks are excluded from the accountability mechanism for redress. “On the exclusion, the AIIB is the only one that does that among all multilateral development banks,” said Kate Geary, one of the authors of the report.

In an interview with China Dialogue, Joachim von Amsberg, the bank’s former vice president, now a special advisor to the bank’s president, Jin Liqun, explained that since multilateral development banks share basic principles and have similar policies, it’s more straightforward for clients to follow one policy. He added: “The story does not end by saying go to the other banks. That’s just the beginning. When the accountability mechanism makes a determination, it goes back to both banks to take appropriate action to address any shortcomings.”

According to the report, in some rare cases AIIB’s accountability mechanism could accept complaints on the projects co-financed with the International Finance Corporation (IFC), even when other IFC policies applied. It shows the AIIB is able to ensure affected people have access to its own mechanism.

Another loophole in the new ESF is for capital market projects. The AIIB allows the application of ill-defined environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards to be developed by individual asset managers, in lieu of ESF requirements.

According to von Amsberg, in cases where AIIB purchases bonds from the market, it cannot apply its ESF since there is no contractual relationship between the bank and the bond’s issuer. “It is not a suspension of the ESF, but implementation to a different mechanism…Our board has to approve each of those operations and the framework for implementing the ESF through the ESG framework.”

“This is especially concerning given the serious lack of information the bank has disclosed on its existing capital market projects,” said Mark Grimsditch, China Global Program Director for Inclusive Development International. As the AIIB increasingly expands its lending to and investing in financial intermediaries and capital markets, “it is important that the bank addresses this transparency gap, disclosing information on these portfolios and providing more detailed information on how it manages this type of investment,” he said.

The bank prides itself on using a “lean” approach to management. Compared to many other multilateral development banks, it is quite small. It has just over 300 employees and has opened only one office outside its headquarters in Beijing. On the question of seeking the balance between lean and green, von Amsberg said: “the answer is through careful selection of our partners”. However, many observers question if balancing these values may in practice mean cutting corners on necessary due diligence.

Shi Yi is formerly a senior researcher at China Dialogue. She was an environmental journalist with The Paper, a major Chinese news website.

Wawa Wang, program director of Just Finance International, affiliated with Danish non-profit VedvarendeEnergi

(Sources: China Dialogue)