If all the actors in the supply chain were treated fairly, consumers would barely notice the premium for sustainable palm oil products. Multinationals could play a much bigger role.

Palm oil is one of the most widely traded and used commodities. Ubiquitous in cooking oils, detergents and beauty products, it is also found in over half of all packaged foods on supermarket shelves. Over 85% comes from Indonesia or Malaysia, where clearing land to meet rapidly increasing demand for the product has severely damaged forest ecosystems and caused huge carbon emissions. Palm oil production is also frequently associated with the infringement of land rights, forced labour and sexual harassment. These problems have led to calls for an end to the use of the product. In response to its environmental impacts, the European Union has decided to end its use in biodiesel production by 2030.

In 2004, various stakeholders in the palm oil sector, such as Unilever, WWF and the Malaysia Palm Oil Association, responded to public concern about these issues by creating the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a voluntary international certification system for palm oil intended to promote environmental and social sustainability. The RSPO is currently the globally dominant sustainability framework for non-biodiesel uses of palm oil.

But according to the RSPO’s own figures, the proportion of global production covered by its certification has hovered at around 19% since 2014, with no sign of a breakthrough. And the 19% that is certified goes primarily to the EU and US markets, where certified products have a higher market share because of consumer awareness. The main reason for the stagnation is a lack of demand from developing world markets – and those very markets are the biggest consumers of palm oil. In the two biggest markets, China and India, RSPO-certified palm oil accounted for a mere 4% and 3% of consumption, respectively, in 2019. A breakthrough in those two countries would have far-reaching implications for the global palm oil landscape.

That certification makes palm oil more expensive is seen as an obstacle to a breakthrough. In China, manufacturers often say they cannot use more sustainable palm oil, as consumers will not pay the extra. This has led to somewhat of a stalemate.

The same situation can be seen in upstream producer nations. “A majority of growers appear to regard the RSPO certification as ‘an unjustifiable cost’ given that the price premium for certified oil is negligible,” said R.H.V. Corley, an industry expert and formerly head of research for Unilever Plantations, in a 2018 article entitled “Does the RSPO have a future?“

So, for downstream manufacturers, the price premium is too high. For upstream producers, it is too low. What’s actually going on?

Upstream producers aren’t benefiting from price premiums

To obtain certification, producers need to meet eight RSPO principles, including on responsible land use, conservation, compliance and transparency. Third-party audits are required before certification can be granted. But compliance with those standards incurs extra costs.

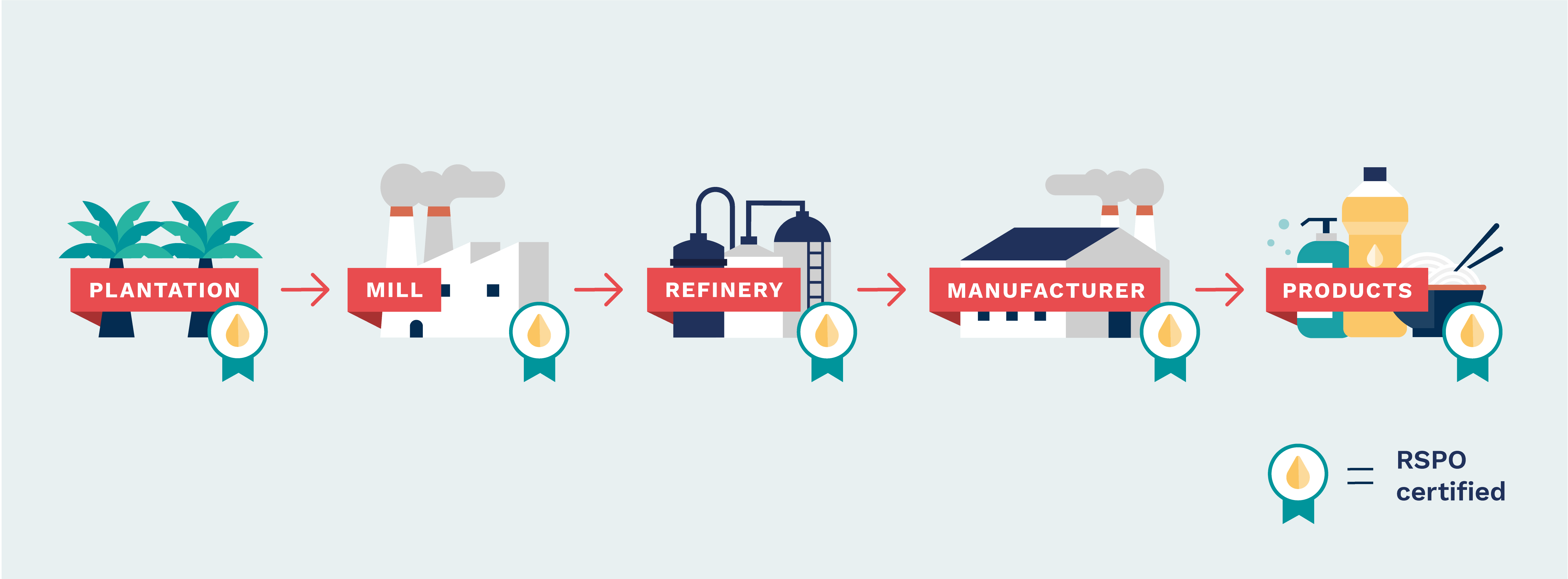

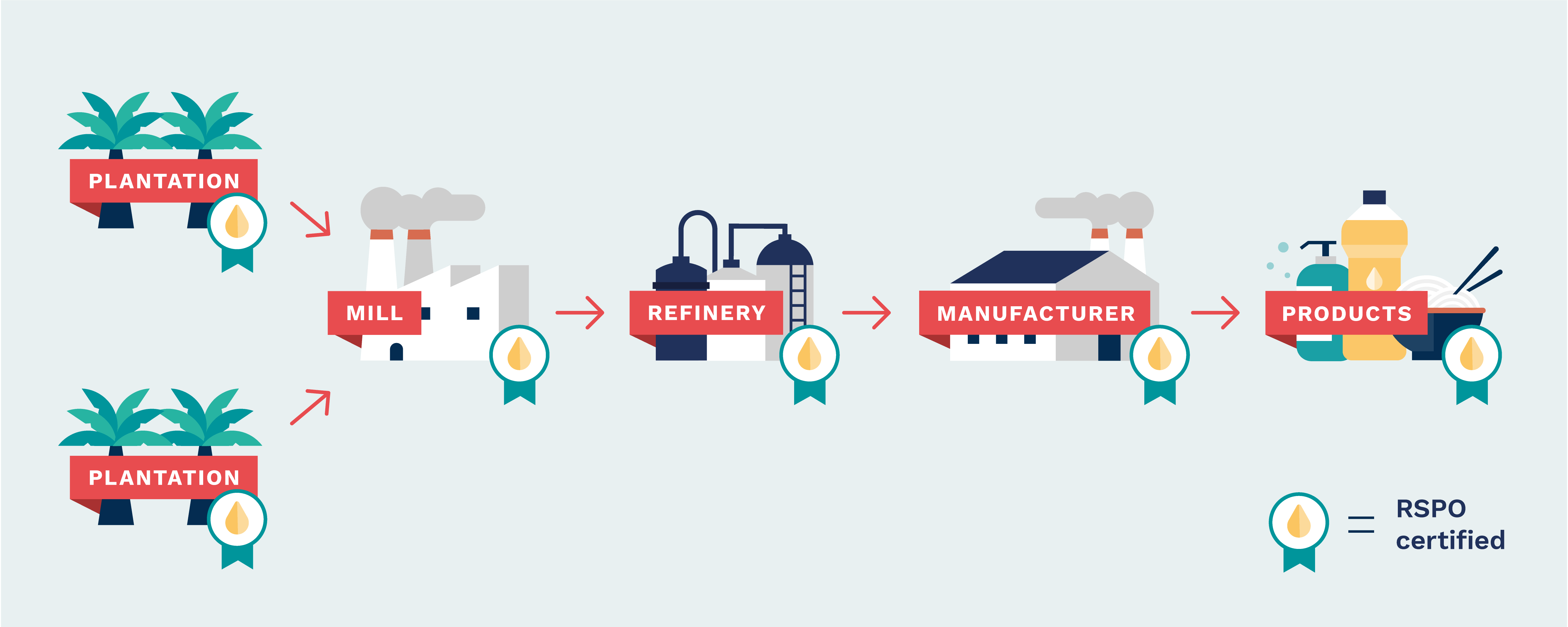

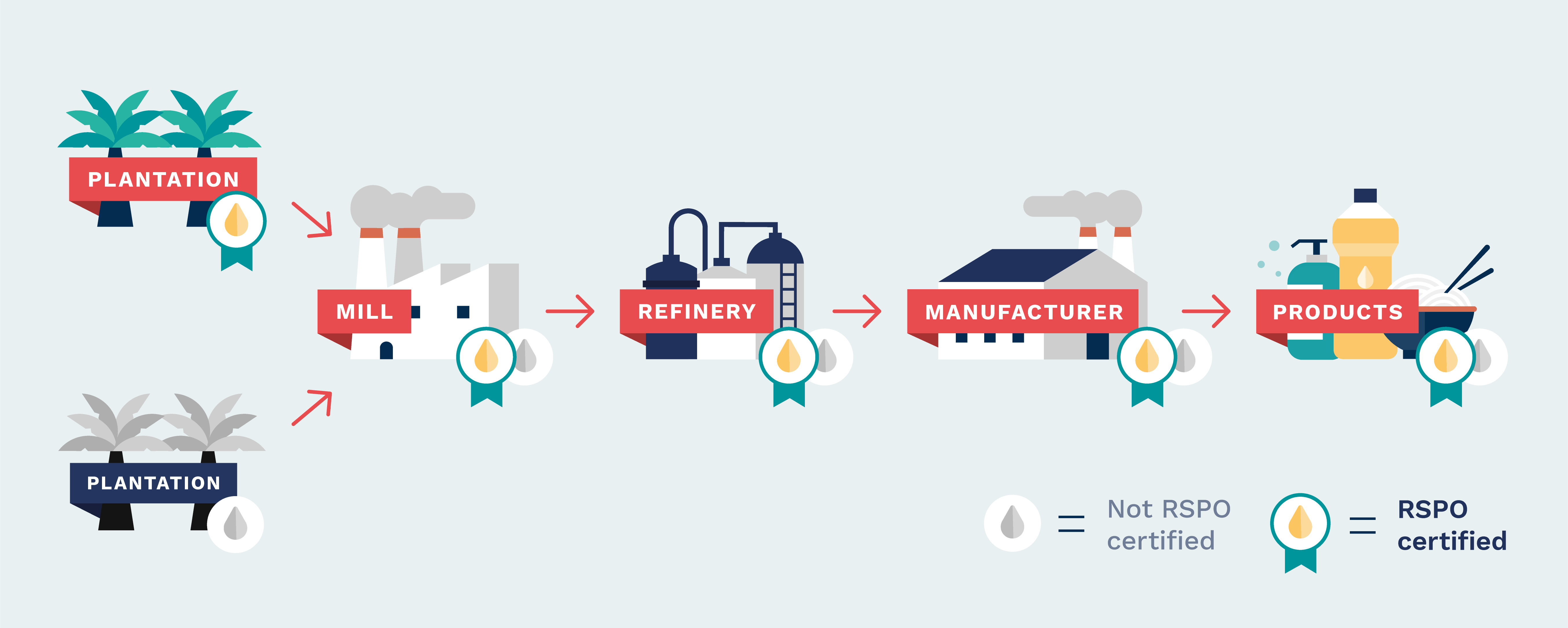

Along the supply chain, RSPO certification has four different levels based on traceability. The two highest levels are “identity preserved”, where the original plantation can be identified, and “segregated”, where certified palm oil is not mixed with uncertified. “Mass balance“ sees the two types of palm oil mixed, but records kept of proportions. This provides less traceability, but is cheaper. The final level, “book and claim”, sees downstream manufacturers make transfer payments to sustainable producers in exchange for RSPO credits. This is the cheapest but still supports sustainable production.

The price of crude palm oil has varied between US$530 and $1,000 over the last five years. According to research carried out in 2019 by Proforest, a UK organisation, and the WWF’s Indonesian branch, the premium paid for crude palm oil was lowest when the book and claim method was used, at around US$2.50 to $3.50 per tonne. That rose to US$6-17 for mass balance palm oil, and US$25-30 for the two highest levels. Premiums fluctuate with market demand.

The report also pointed out that usually only large, vertically integrated companies are able to obtain the RSPO’s two highest levels of supply chain certification. In general, it is the bigger firms that benefit from the price premium, rather than small companies and producers – although even they say it can take years to recoup costs. According to the report, “RSPO compliance costs for CSPO [certified-sustainable palm oil] are usually higher than the premium”, and “the RSPO’s direct appeal is not self-evident to many smallholders and the premium and levels of demand are uncertain.”

The challenge for small-scale farmers

Small-scale farmers are in a particularly difficult position. According to the report, smallholders in Indonesia pay the equivalent of US$8-12 per tonne for certification. Even if they are able to sell their sustainable palm oil credits under the book and claim arrangement, the payment they receive barely covers that extra cost, and “if the smallholders are unable to sell 100% of the certificates, there would be a financial shortfall”.

An estimated 40% of palm oil production originates on farms of less than 50 hectares. The remainder comes from larger commercial plantations. According to the latest data from the RSPO, certified sustainable palm oil produced by smallholders accounts for only 8.77% of the global total.

Robert Hii, founder of independent website CSPO Watch, has seen the same thing. He says that demand for sustainable palm oil is currently driven by the few western buyers who need it. These firms already have RSPO membership and require growers to become certified too. The farmers do so only to get a chance to win the orders. But growers who obtain the certification often see orders fail to materialise, or obtain only short-term and unstable orders. In other words, growers bear the risks of certification, but not necessarily the benefits.

Hii also revealed that some large, listed palm oil growers obtain certification despite costs outweighing the price premium, in order to avoid reputational damage affecting their share prices. In these cases, they obtain the lowest level of certification, with limited impact on the overall sustainability of the industry.

Supermarkets and big brands keep most of the profits

The minimal benefits, or even losses, incurred by producers, reflect existing imbalances in how profits from palm oil, certified or not, are distributed. The refining, processing and trading of palm oil is concentrated in the hands of a few major players, while downstream manufacturers and retailers have an advantage in marketing and price-setting. Gerard Rijk, senior equity analyst with Dutch consultancy Profundo, told China Dialogue that in their studies of the sugar and soy supply chains, it is supermarkets and brand manufacturers that keep most of the profits. “We are currently in the middle of the profit chain study on palm oil. But it might share similar characteristics to soy and sugar,” said Rijk.

Ian Suwarganda, head of policy and advocacy for palm oil plantation company Golden Agri-Resources, suggests that rather than focusing on the cost of sustainable palm oil, Chinese firms should look at the overall costs of their products. Palm oil makes up only a small part of that, and any premium will have little effect. “Thus with a minor cost increase on the buyer side, the Chinese market can have a major impact on sustainable production on the seller side,” he said.

Gerard Rijk agrees. He told China Dialogue that palm oil is crucial for makers of consumer products. For example, products containing it account for 20–40% of Proctor and Gamble’s turnover. However, if the company were to spend money on a best-in-class process in palm oil policy execution, due diligence and verification, the price of Procter & Gamble’s Head and Shoulders shampoo would have to increase by only 0.12% to cover the costs. “If this is really the argument that sustainable palm oil is too costly, then investors should engage with these companies to tell them that it is nearly no cost for them at the endpoint in the chain,” said Rijk.

Robert Hii added that as in most products palm oil is used as a side ingredient, downstream multinationals could easily swallow even a US$30 premium per tonne. But in their Annual Communication of Progress reports submitted to the RSPO, those firms often blame their failure to use sustainable palm oil outside of the EU and US markets on “a lack of consumer demand”. Hii agrees that there is little demand, but says the multinationals are unwilling to work to change that, despite being able. They only buy enough sustainable palm oil to ward off criticism from NGOs.

He thinks that if multinationals signed long-term contracts with palm growers, with a floor price guaranteeing a return, growers would be motivated to get certified.

Multinationals should play their part in sustainable palm oil

There are many big brands downstream, concerned for their reputation and able to raise awareness among consumers about sustainability. In his earlier-mentioned article, R.H.V. Corley pointed out those firms could use sustainability certification as a selling point to create a new niche market. But that won’t resolve the environmental and social issues associated with palm oil production. If sustainable palm oil is going to break out of niche markets, the multinationals will have to do their bit. He would like to see RSPO members that are downstream in the palm oil supply chain produce time-limited plans to shift to 100% sustainable palm oil use, with audits, just as is currently the case for producers. Currently, the RSPO does not require member companies to be certified, or make such commitments.

“If all CSPO is taken up and there is further unmet demand, the price premium should increase, and the plantation industry might start to see that there is an advantage to RSPO membership,” Corley wrote.

Sandeep Bahn is chief operations officer at Sime Darby Oils, a subsidiary of the world’s biggest producer of CSPO, Sime Darby Plantation. He told China Dialogue: “The use of the term ‘premium’ is actually quite misleading. It is about cost sharing for better sustainability practices on the ground.”

Last year, the China Council on International Cooperation on Environment and Development published a report on the greening of soft commodity supply chains in China, reflecting a buyer’s concern for stable prices. According to the report, if China sends signals that it would prefer sustainable palm oil and gradually increases its market share, producer countries will have both the time and motivation to increase output, ensuring prices remain stable.

Ian Suwarganda takes a similar view. He thinks that while increased demand from China could push the price premium up in the near term, it would also encourage growers to become certified, reducing the gap between supply and demand and so shrinking the premium again.

The premium represents extra costs for buyers and extra profit for sellers at the same time. Neither higher nor lower premiums are necessarily better. What is important is including sustainability in the price of products, and ensuring all actors in the supply chain are treated fairly, so that pricing helps the market develop. But a lack of mechanisms to transmit price signals are hampering this.

There is certainly a lack of demand for RSPO-certified palm oil; the RSPO says that globally only half of production is sold as such. But that may be an overstatement. In March last year, the United Nations Development Programme’s China Office published a report pointing out that much of the “unsold” sustainable palm oil also has International Sustainability and Carbon Certification (ISCC) and is sold to the EU to be used in biofuels. The ISCC was designed to meet traceability and greenhouse gas standards for the biomass and renewable energy sectors. Currently, 65% of the palm oil imported by the EU is used to make biofuels.

Khor Yu Leng, a business economist and one of the main authors of the WWF and Proforest report mentioned above, also points out that many growers obtain both RSPO and ISCC certification, so they can better respond to market demand. The RSPO requires producers to have all their production units certified, while the ISCC allows for partial certification according to needs. This makes it easy for an “oversupply” of RSPO certified palm oil to exist in name only, while supply and demand for ISCC palm oil is more balanced. This means it is not the case that half of RSPO certified oil is sold as uncertified. However, it is unclear what premium is charged for ISCC certified oil being sold to the biofuels market.

And this highlights an issue: as there is more than one certification regime in place, and a lack of openness or transparency on premium pricing, the sustainable palm oil sector lacks transparent and effective mechanisms for passing on price information, which prevents growers from adjusting their output in line with downstream demand.

According to Khor, demand for palm oil from the EU is likely to stay stable in the near term, despite a commitment to stop imports for biofuel by 2030. Given this, she says: “The premium of certified sustainable palm oil will likely rise if new players, such as fast-moving consumer goods companies from Japan or China, start to buy certified palm oil and its derivatives. That will cause a shortage of certified palm oil rather than an oversupply, and the premium will go higher. That, in turn, could stimulate new supply.”

But, she added, the RSPO provides only some price data, while the ISCC provides none. That means downstream price signals may not reach upstream producers and prompt greater production. Robert Hii has found that firms whose businesses span growing, processing and trade in palm oil have better information on price signals, but smallholders and plantations have none.

Khor Yu Leng mentioned another class of initiatives alongside the two main certification schemes of the RSPO and the ISCC: the industry-led NDPE (No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation) commitment and traceability. This creates a third sustainable palm oil sub-market, adding to the confusion over pricing signals.

For the moment, the cost of producing certified palm oil is unequally distributed across the production chain, with upstream producers covering higher production costs and certification fees while those further downstream are profiting off it. To make the process fair and equitable, those with the means to shoulder the costs should be doing more to make the process of certifying palm oil more feasible for smallholders.

Đăng nhận xét