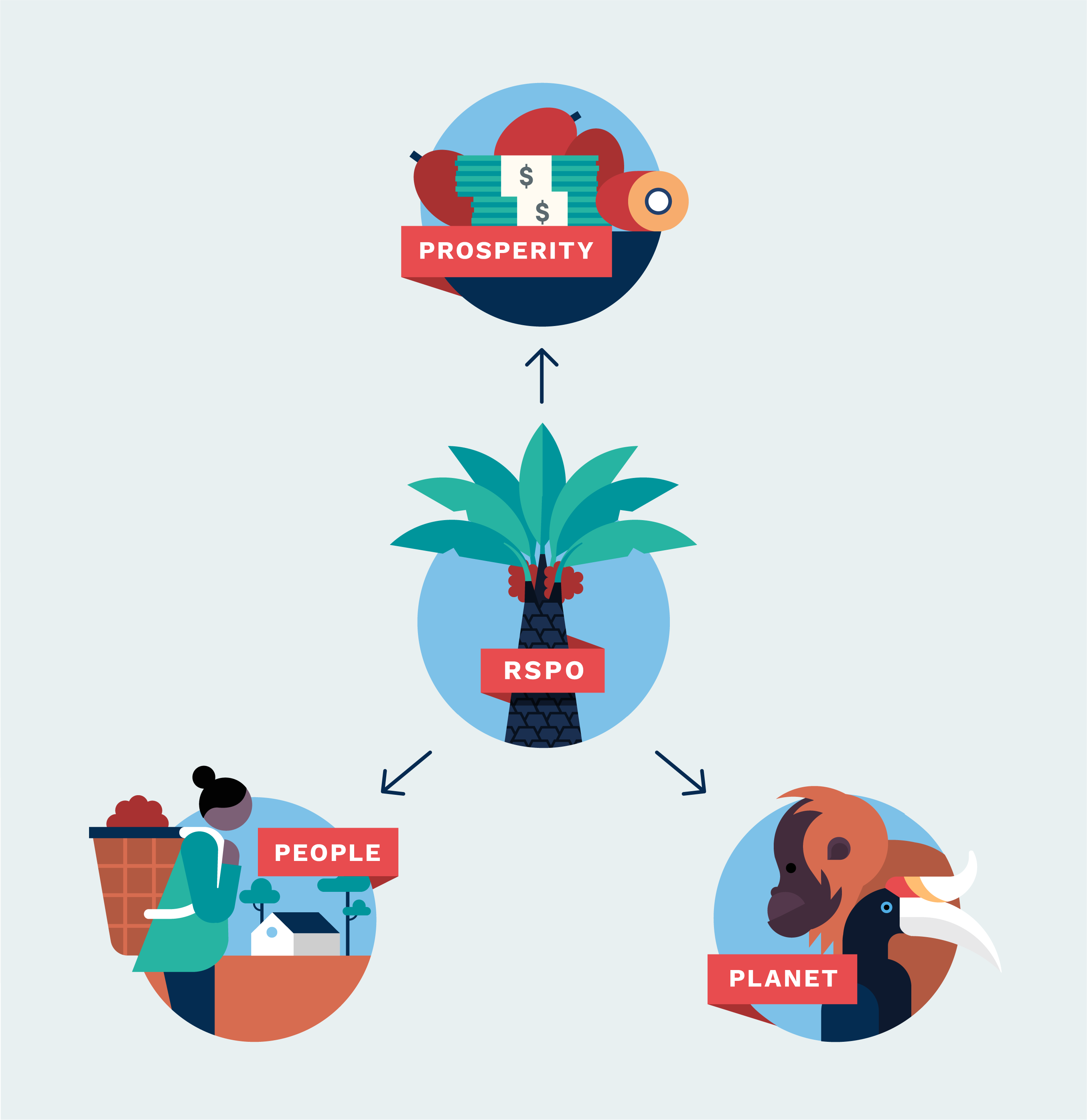

The RSPO’s standards are a flagship in the drive to make palm oil sustainable. But much more is needed to truly bring change.

In 2004, a new entity was formed with big goals to end deforestation, stop environmentally harmful practices and improve ethical sourcing in the palm oil industry, which was increasingly being linked to widespread fires, habitat loss and human rights violations in Southeast Asia.

That entity was the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), founded by leading industry actors together with the World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF). Sixteen years later, despite measurable progress and continuous efforts to improve the practices of its certified producers, the organisation has been criticised on many levels. It has been accused of being beholden to industry, enabling greenwashing and for being slow to act when alerted to violations by its members. Some believe the path forward is to improve the RSPO from within, but others believe alternative models may be a better route to ensuring sustainability in the palm oil industry.

“A multifaceted approach is what we need to drive change in the industry,” said Michael Guindon, global palm oil lead with WWF in Singapore. “Certification is one element that’s going to lead to widespread transformation of the palm oil sector.”

While the RSPO is the largest and most recognisable standard, there are in fact many other approaches. Some attempt to utilise several certification schemes, while others focus on empowering smallholders, or take a “landscape” approach, covering all commodities grown within a particular area. Companies across the palm oil supply chain are also making independent efforts to better map their palm oil sourcing. Despite this, whether or not palm oil can become a fully sustainable industry will depend on deepening the impact of existing entities like the RSPO, along with more collaboration by major actors along the supply chain.

Challenges for the RSPO

Despite strengthening standards, major concerns with the RSPO centre around its enforcement mechanism and auditing system.

“[The] RSPO has an appropriate standard, but the system is inadequate at upholding that standard,” said Robin Averbeck, forest programme director at Rainforest Action Network (RAN), an environmental non-profit organisation based in the United States.

For example, it took the RSPO nearly 2.5 years to suspend the certificates of Indofood after being presented with evidence of sustainability and labour rights violations by RAN and its partners in late 2016. Similarly, it took three years to follow up on labour abuse allegations on plantations run by FGV Holdings Berhad (FGV), one of Malaysia’s largest palm oil companies, which led to a partial sanctioning in 2018. The RSPO then conditionally lifted this in August 2019, only to have it reinstated the following January. In the end, FGV saw itself subject to a withhold release order from the US Customs and Border Protection authority due to the same labour violations – a move over which the RSPO “expressed reservations”.

“We haven’t seen the RSPO play the role that it should yet, because [they] have repeatedly allowed bad actors to be RSPO members,” said Averbeck.

A report entitled “Who Watches the Watchman? 2” released by the Environmental Investigation Agency and Grassroots in late 2019, found that little has changed since 2015, when their first report accused the RSPO of “extensive fraud as well as sub-standard and underhand assurance processes”. They found the action taken by the RSPO since the first report to be “severely lacking”.

Sustainability is still a long way off

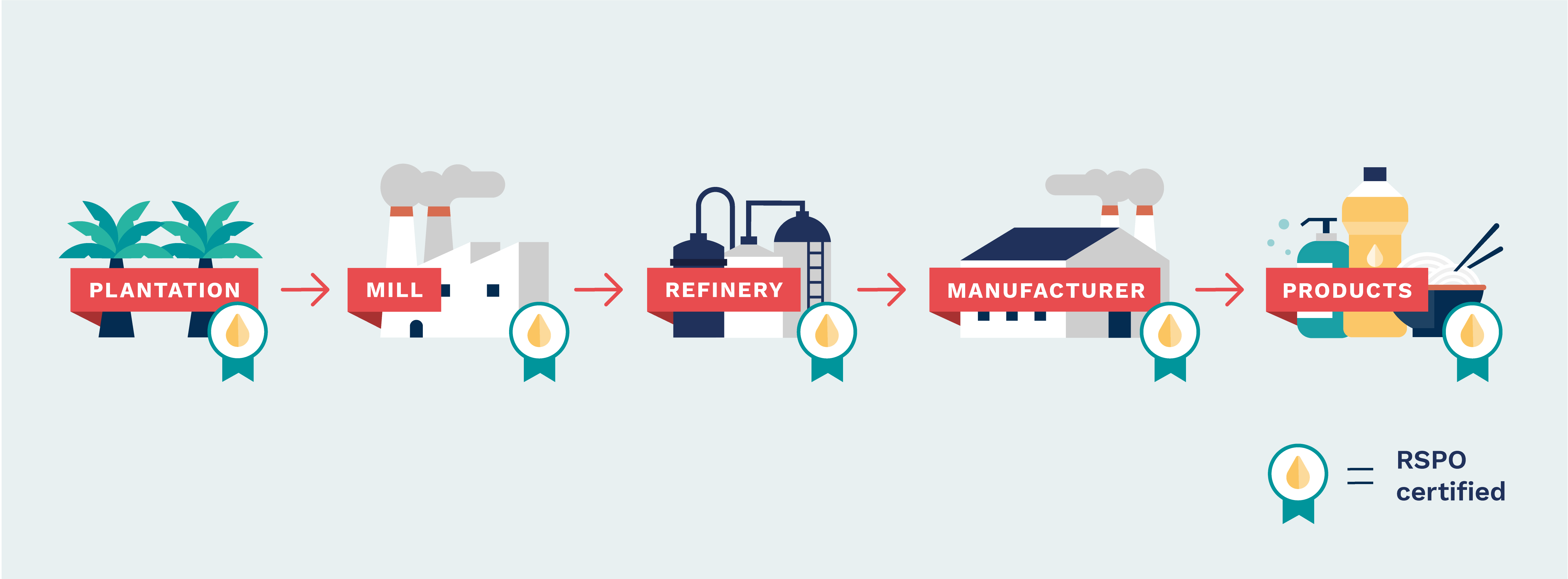

Another issue is that the RSPO has yet to achieve its goal of transforming the industry and making sustainable palm oil “the norm”. Only 19% of palm oil produced globally is RSPO certified, meaning the vast majority is at risk of being connected to deforestation, fires, human rights abuses and other environmental and land-use issues.

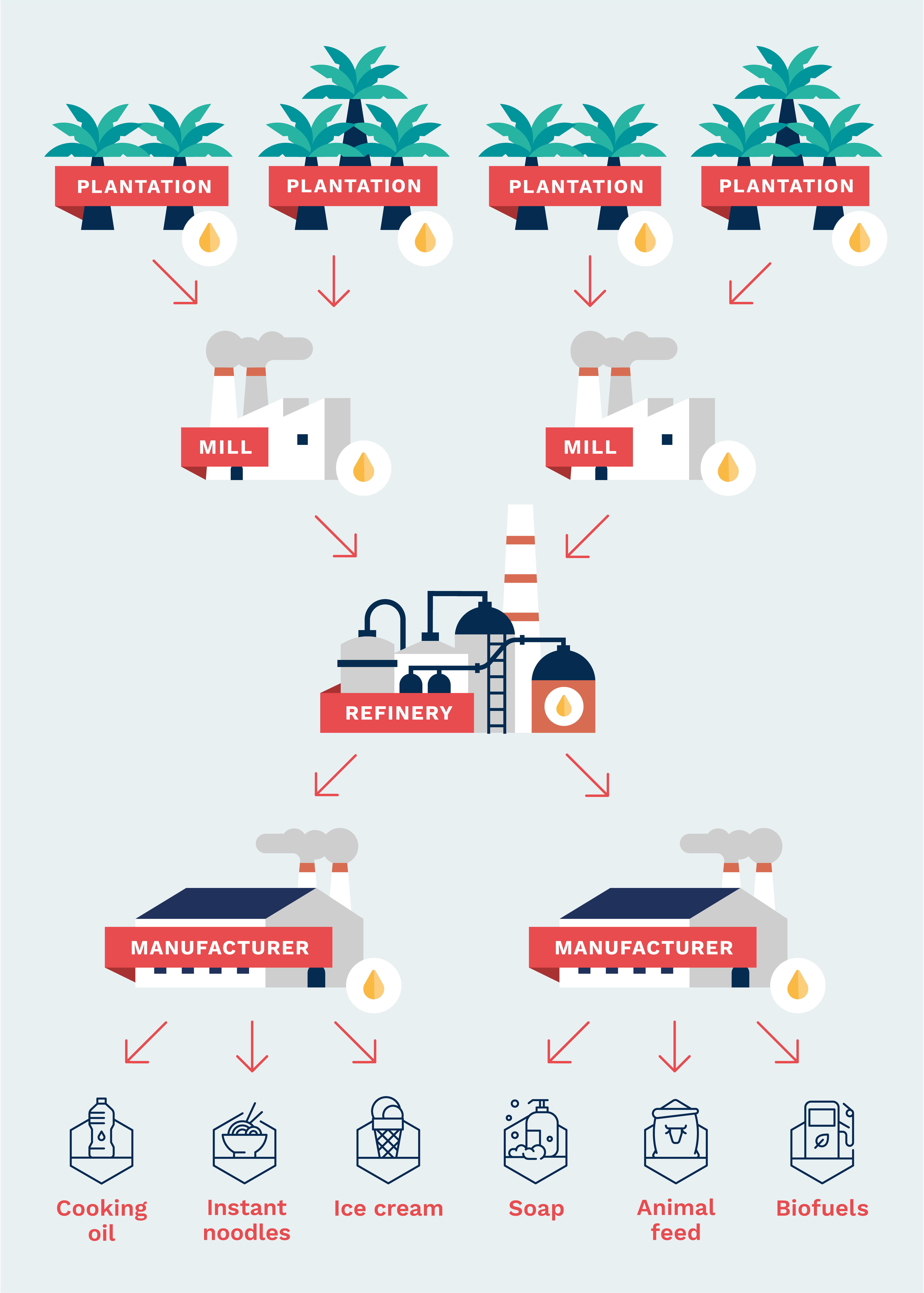

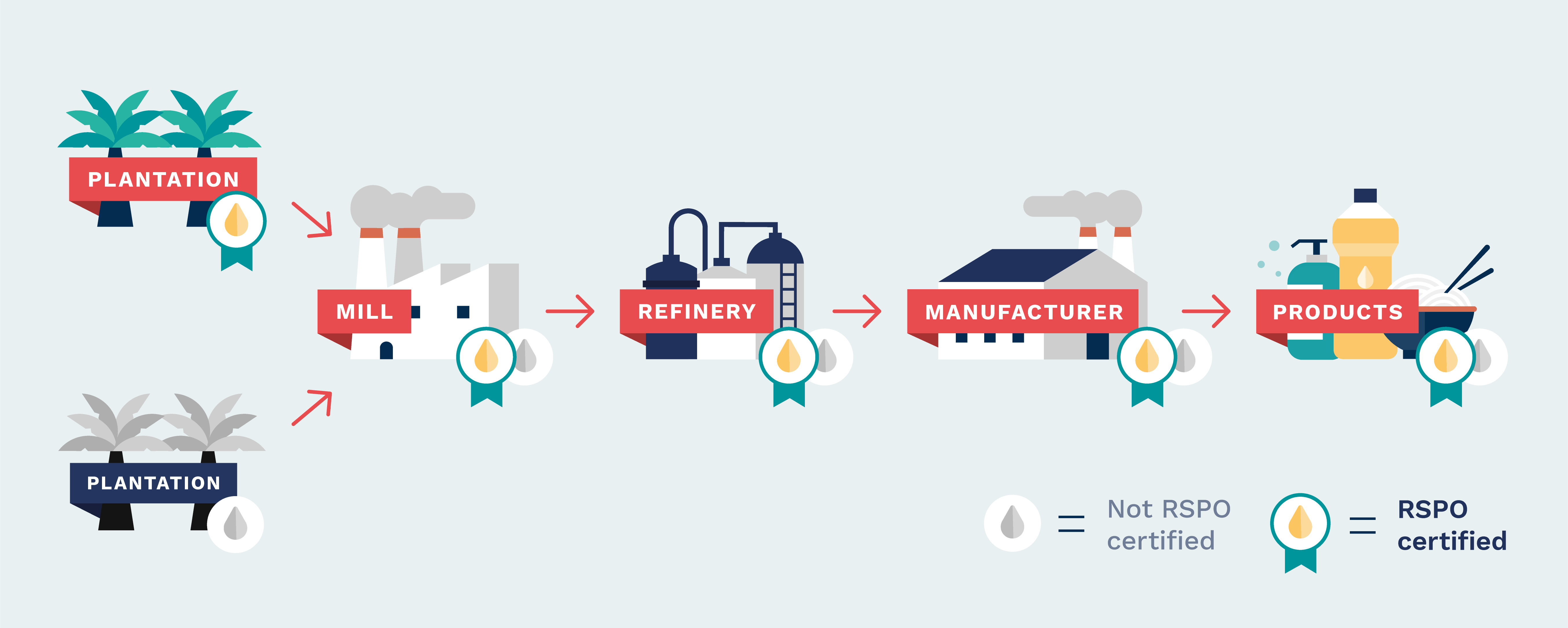

Even companies that are RSPO members, and have committed to achieve full RSPO certification across their supply chains, are not guaranteed to be producing palm oil that is deforestation free. Wilmar International is estimated to control 40% of the global palm oil supply chain through its subsidiaries, but it purchases palm oil from third-party suppliers, increasing the risk of “leakage” – palm oil linked to deforestation finding its way into the certified supply chain.

The lack of progress over 16 years and the RSPO’s shortcomings, together with high-profile NGO campaigns using the plight of charismatic animals such as the orangutan to highlight deforestation and demonise palm oil production, have led some brands to choose a dramatic form of certification: palm oil-free.

“Protecting the world’s rainforests will only be achieved by many conservation groups and companies making more palm oil-free products, consumers reducing their demand for palm oil, NGOs fighting for rainforests, [and] companies who choose to use palm oil only using identity preserved certified sustainable palm oil,” said Bev Luff, co-manager of the Palm Oil Free Certification Trademark.

One of the concerns is that growth in sustainable production in one place could result in shifting unsustainable production elsewhere through a spillover effect. A study released in June 2020 and published in Environmental Research Letters found that in Indonesian Borneo, while RSPO certification reduced forest loss in some areas, it increased deforestation in adjacent areas. It concluded that “while certification has reduced illegal deforestation, stronger sector-wide action appears necessary to ensure that oil palm production is no longer a driver of forest loss.”

According to Luff, about 40 companies have been certified by their palm oil-free standard so far, including Illumines Skin Care, Earth Sense and Meridian. Many more are in various stages of the assessment process. Part of this involves educating brands about palm oil use through derivatives they might not even be aware of.

“It is very difficult for the company wanting to make palm oil-free products to know which ingredients contain palm oil derivatives,” said Luff. “If after assessment we conclude a company is unknowingly using a palm oil derivative, then we try to help them find a palm oil-free replacement ingredient.”

Emerging alternative models

For the most part, palm oil does not often have readily available alternatives. And when it does, these can could have their own detrimental environmental impacts. In order to address the shortcomings of the RSPO, there are several NGO- and industry-led alternatives, most of which see themselves as complementary, or building upon, RSPO certification.

The Palm Oil Innovation Group (POIG) was founded in 2013 with the goal of going beyond the RSPO through stronger standards and better verification.

“We undertook a process to create a verification approach that would address a number of the gaps that we were seeing,” said Averbeck. This includes requiring that the entire company – not just specific plantations – be certified, and a more robust auditing system with stronger social and labour standards. In fact, many of POIG’s innovations were adopted by the RSPO when it updated its standards in 2018.

“POIG demonstrating that ‘no-deforestation, no-peat and no-exploitation’ standards were possible was influential,” said Averbeck. “We were able to both advocate and demonstrate that better practices and responsible production were possible.”

Meanwhile, in Latin America, Palm Done Right started as an effort not to transform the whole industry, but to work with smallholder farmers in Ecuador to implement sustainable practices, starting with organic certification.

“When we talked to mission-driven brands and buyers, there was a need to progress beyond organic,” said Monique van Wijnbergen, spokesperson for Palm Done Right. “That’s when we started to work with the RSPO, Fair for Life [and the] Rainforest Alliance, all of which helped us improve and progress on environmental and social sustainability.”

In fact, van Wijnbergen saw value in having several certifications, rather than just one.

“There’s a lot of overlap, but it helps us in what we are doing,” she said. “Organic stands out due to the practices and natural interventions. Fair for Life has a strong community check, and with the new RSPO standards, there’s the high-carbon stock approach. There are different values in different standards.”

Currently, Palm Done Right works with 200 independent organic growers in Ecuador, who in total grow oil palm on about 10,000 hectares. That feeds into the 550,000 tonnes of palm oil produced globally that is certified by the Rainforest Alliance (RA) under their Sustainable Agriculture Standard, which works for other commodities too, such as coffee, bananas and cacao. These are often grown alongside or with oil palm on smallholder plantations, a particular focus for the organisation.

“Smallholders are also an important piece here. They are on about a third of the land cultivated for palm oil,” said Paula den Hartog, sector lead for palm oil at the RA. “That is why we’re prioritising engaging with smallholders to improve their resilience and livelihoods, and to link them to global markets to set the stage for them to implement more sustainable practices.”

While the RA’s standard is separate from the RSPO’s, it is a member and does work with it on traceability.

The RSPO’s limitations in working with smallholders were a reason that Traidcraft Exchange, a United Kingdom-based social enterprise, decided to have their smallholder palm oil producers in Africa be certified by Fair for Life, a fair trade certification entity and the only one currently working in the palm oil sector.

“The RSPO doesn’t seem to be a model that fully embraces smallholder production,” said Alistair Leadbetter, supply chain development and business support manager at Traidcraft. “We were much happier to go with Fair for Life. We’re not against the RSPO, but it wasn’t for us, because we wanted to focus on smallholders.”

In the fair trade model, brands pay a premium for fully traceable palm oil grown based on a range of labour, community and sustainable standards. The premium goes directly to local farming communities. At present, however, palm oil seems to be a very small segment of global fair trade commodities.

Companies taking independent action

Another emerging trend is large multinational corporations, with either a significant palm oil footprint or complex supply chains, working to verify their sources independent of certification schemes.

COFCO International, which imported 11% of China’s palm oil in 2018, has a strong sustainable palm oil sourcing policy that requires all their palm oil suppliers and sub-tier suppliers to comply with their Supplier Code of Conduct. This means their commitment to the RSPO is just part of their sourcing efforts.

“We see certification as being one way towards sustainable sourcing, but not the only way,” said Wei Peng, global head of sustainability at COFCO International. “Our supply base mapping and risk management is our primary way to ensure we deliver on our commitment.”

The company is working with ProForest, an NGO, to map its entire supply chain in detail to help analyse risks. They’ve even committed to releasing a list of their supplying mills every year. Other big brands, such as Unilever and Mondelez International, also release their mill data.

Unilever is one of the world’s largest consumer goods companies, and it procures palm oil from at least 150 refineries and oleochemical plants, which in turn source from at least 1,500 mills. While the company has committed to buying from RSPO- and RA-certified mills, they also saw a need to better understand which plantations were selling oil palm to their mills, and whether or not they were following the company’s sourcing policy. To do that, they partnered with Orbital Insight, a California-based geospatial analytics start-up.

“We look at billions of pings of mobile phone data,” said Zac Yang, director of solutions engineering at Orbital Insight. “That data in aggregate results in a pattern of traffic, which says: this is your actual sourcing footprint, based on the patterns of movements of truck drivers.”

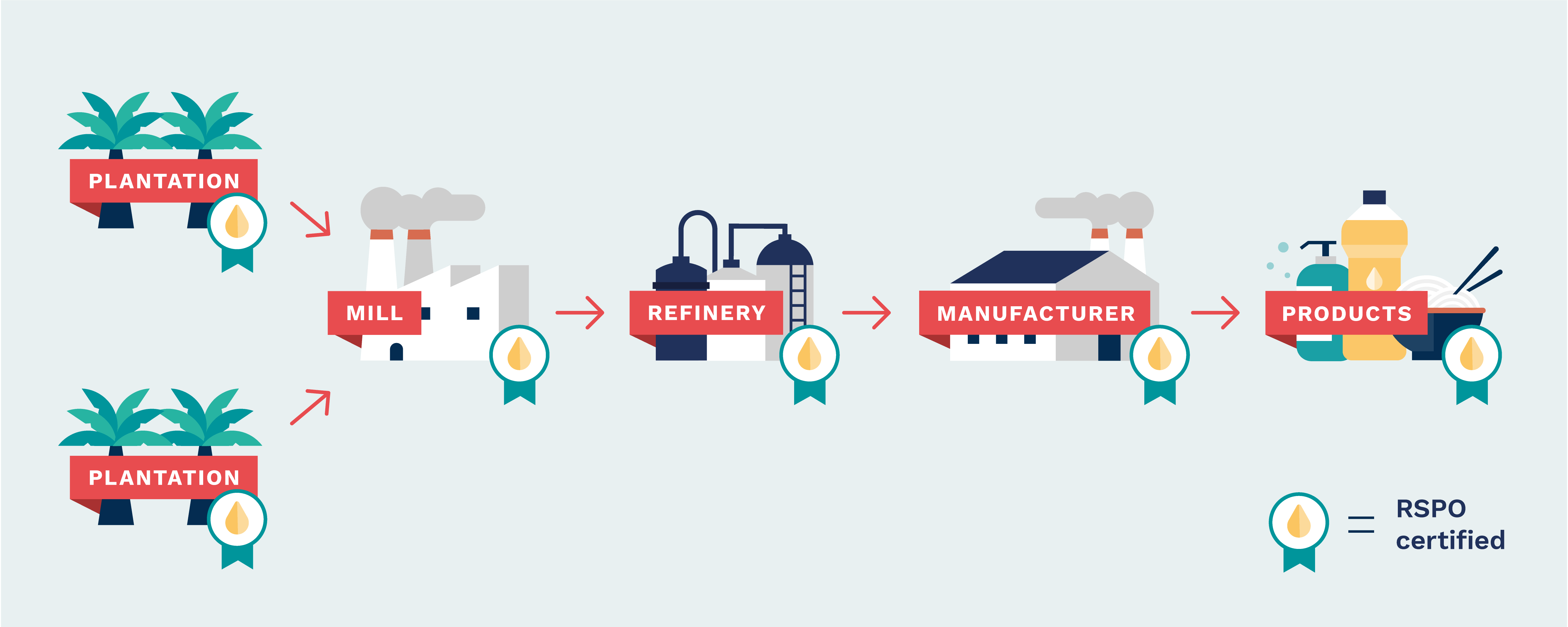

This allows Unilever to address one of the key challenges with certification: tracing that first mile from plantation to mill. Mills often source from several plantations, and the oil produced is often a mix sourced from sustainable and unsustainable plantations. This type of technology could enable much broader mapping and understanding of the palm oil supply chain in real time, and Orbital Insight is looking at working with other major global food and beverage brands.

“Where we’re going is a method that works with big data and AI algorithms that can process and analyse this at scale,” said Yang. “It’s inherently much more cost effective and scalable to run around hundreds and thousands of mills.”

Unilever, along with PepsiCo, are two of the early partners in a new approach being piloted by IDH (the Dutch acronym for The Sustainable Trade Initiative), a social enterprise based in the Netherlands, to certify particular jurisdictions as Verified Sourcing Areas (VSAs).

“If you are sourcing from that area, you know exactly what is happening in sustainability in that area, and you also know that people are working to improve it,” said Guido Rutten, senior manager at IDH. “There’s a huge demand for new solutions for supply chain sustainability, and for landscape approaches in particular, from companies in the West, but also in other demand markets like in India and China.”

IDH’s current pilot projects are in Indonesia’s Aceh and southern India. The VSA approach is focused on the landscape, meaning that any commodity grown in a verified region – oil palm, cacao, coffee – all comes under the same standard.

Beyond certification

There are concerns that certification may have reached a limit. After strong growth in its initial years, the RSPO’s figure for certified sustainable oil has been stuck around 19% for the last few years. Getting to 100% looks as distant now as it did when the organisation was founded in 2004.

“You’re never going to see all of global palm oil be certified,” said the WWF’s Guindon.

Part of the challenge, according to Guindon, is growth in Asian demand, which now accounts for 60% of all palm oil consumption. There’s far less demand for certified sustainable oil in India, China or Southeast Asia compared to the European Union, where already 86% of palm oil bought by the food industry is certified.

Building demand for it in Asia is one path forward, but Guidon sees greater opportunity in improving the standards for companies that are already RSPO members.

“RSPO members, if you look at the traders, they cover 90% of palm oil trade,” he said. “If we put requirements beyond sourcing sustainable palm oil, that could have widespread impacts.”

Averbeck, of the Rainforest Action Network, believes that the burden lies with companies to expand their efforts, especially after recent reports that many have either failed, or are on track to miss, their own zero deforestation goals.

“Companies have put their commitments out there, yet they haven’t invested resources in actually implementing those commitments,” she said.

Đăng nhận xét