On the 20th anniversary of the graph that galvanized climate action, it is time to speak out boldly

By Michael E. Mann on April 20, 2018

Credit: Getty Images

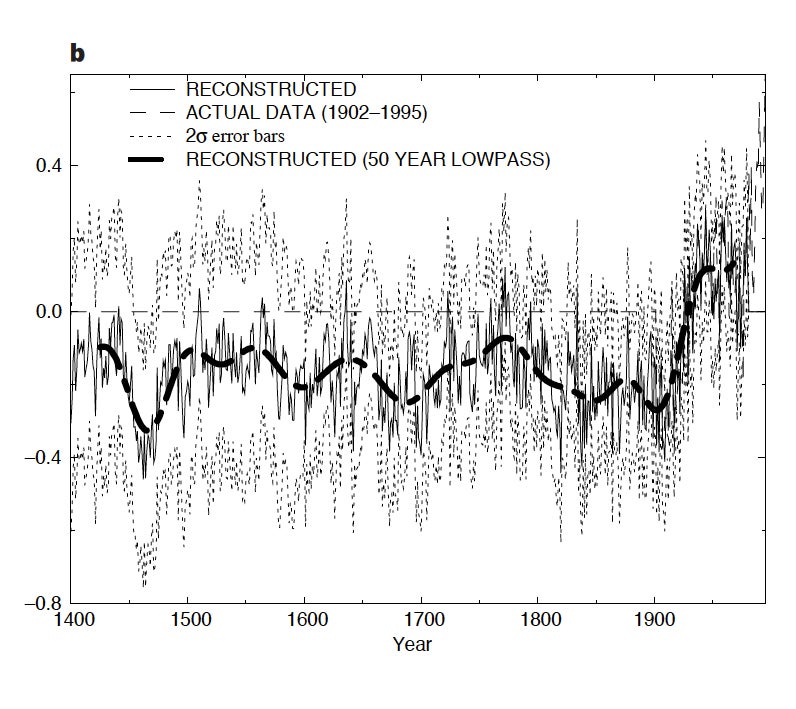

Two decades ago this week a pair of colleagues and I published the original “hockey stick” graph in Nature, which happened to coincide with the Earth Day 1998 observances. The graph showed Earth’s temperature, relatively stable for 500 years, had spiked upward during the 20th century. A year later we would extend the graph back in time to A.D. 1000, demonstrating this rise was unprecedented over at least the past millennium—as far back as we could go with the data we had.

Although I didn’t realize it at the time, publishing the hockey stick would change my life in a fundamental way. I was thrust suddenly into the spotlight. Nearly every major newspaper and television news networkcovered our study. The widespread attention was exhilarating, if not intimidating for a science nerd with little or no experience—or frankly, inclination at the time—in communicating with the public.

Nothing in my training as a scientist could have prepared me for the very public battles I would soon face. The hockey stick told a simple story: There is something unprecedented about the warming we are experiencing today and, by implication, it has something to do with us and our profligate burning of fossil fuels. The story was a threat to companies that profited from fossil fuels, and government officials doing their bidding, all of whom opposed efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. As the vulnerable junior first author of the article (I was a postdoctoral researcher), I found myself in the crosshairs of industry-funded attack dogs looking to discredit the iconic symbol of the human impact on our climate…by discrediting me personally.

In my 2013 book, The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars: Dispatches from the Front Lines, I gave a name to this modus operandi of science critics: the Serengeti strategy. The term describes how industry special interests and their facilitators single out individual researchers to attack, in much the same way lions of the Serengeti single out an individual zebra from the herd. In numbers there is strength; individuals are far more vulnerable.

The purpose of this strategy, still in force today, is twofold: to undermine the credibility of the science community, thus impairing scientists as messengers and communicators; and to discourage other researchers from raising their heads above the parapet and engaging in public discourse over policy-relevant science. If the aggressors are successful, as I have argued before, we all lose out—in the form of policies that favor special interests over our interests.

As the Serengeti strategy has been deployed against me, I have beenvilified on the editorial pages of The Wall Street Journal and other conservative media outlets, and subject to inquisitions by fossil fuel industry–funded senators, congressmen and attorneys general. My e-mails have been stolen, cherry-picked, taken out of context and broadcast widely in an effort to embarrass and discredit me. I have been subject to vexatious, open-records law requests by fossil fuel industry–funded front groups for my personal e-mails and numerous other documents. I have experienced multiple death threats and have endured threats against my family members. All because of the inconvenience my scientific findings posed to powerful and influential special interests.

Yet, in the 20 years since the original hockey stick publication, independent studies again and again have overwhelmingly reaffirmed our findings, including the key conclusion: recent warming is unprecedented over at least the past millennium. The highest scientific body in the U.S., the National Academy of Sciences, affirmed our findings in an exhaustive independent review published in June 2006. Dozens of groups of scientists have independently reproduced, confirmed and extended our findings, including a team of nearly 80 scientists from around the world who in 2013 published their finding in the premier journal Nature Geoscience that recent warmth is unprecedented in at least the past 1,400 years.

The latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the most authoritative and exhaustive assessment of climate science on the planet, concluded recent warmth is likely unprecedented over an even longer time frame than we had concluded. There is tentative evidence, in fact, that the current warming spike is unprecedented in tens of thousands of years.

Of course, the hockey stick is only one of numerous lines of evidence that have led the world’s scientists to conclude climate change is (a) real, (b) caused by burning fossil fuels, along with other human activities and (c) a grave threat if we do nothing about it. There is no legitimate scientific debate on those points, despite the ongoing effort by some people and groups to convince the public otherwise.

Their preferred tactic is to exaggerate the uncertainty in models that project where climate change is heading and argue such uncertainty is a cause for inaction, when precisely the opposite is the case. Arctic sea ice is disappearing faster than the climate models have predicted. The Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets appear prone to collapse sooner than we previously thought—and with that, estimates of the sea level rise we could see by the end of this century have doubled from previous estimates of about three feet to more than six feet. If anything, climate model projections have proved overly conservative; they are certainly not an exaggeration.

Scientists are finding other examples as well. In part as a result of our own work three years ago, there is an emerging consensus—as publicized in recent news accounts—that the “conveyor belt” of ocean circulation may be weakening sooner than we expected. The conveyor delivers warm waters from the tropics to the higher latitudes of the North Atlantic, supporting vibrant fish communities there and moderating climates in western Europe and eastern North America. The earlier melt of Greenland ice, it appears, is freshening the surface waters of the subpolar North Atlantic, inhibiting the sinking of cold, salty water that helps drive the conveyor.

When the hockey stick was first attacked in the late 1990s I was initially reluctant to speak out, but I realized I had to defend myself against a cynical assault on my science and on me. I have come to embrace that role. What more noble cause is there than to fight to preserve our planet for our children and grandchildren?

There is great urgency to act now if we are to avert a dangerous 2- degree Celsius (3.6-degree Fahrenheit) planetary warming. My own recent work suggests the challenge is greater than previously thought. Yet I remain cautiously optimistic we will act in time. Along with many other Americans, I have been inspired by the renewed enthusiasm of our youth, who are demanding action now when it comes to the societal and environmental threats they face. Indeed, I have committed myself to helping insure a future in which we avoid catastrophic climate change. So let me conclude with this exhortation from the epilogue of The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars:

“While slowly slipping away, that future is still within the realm of possibility. It is a matter of what path we choose to follow. I hope that my fellow scientists—and concerned individuals everywhere—will join me in the effort to make sure we follow the right one.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

Đăng nhận xét