Instead of disappearing, the pesky rodents proliferated.

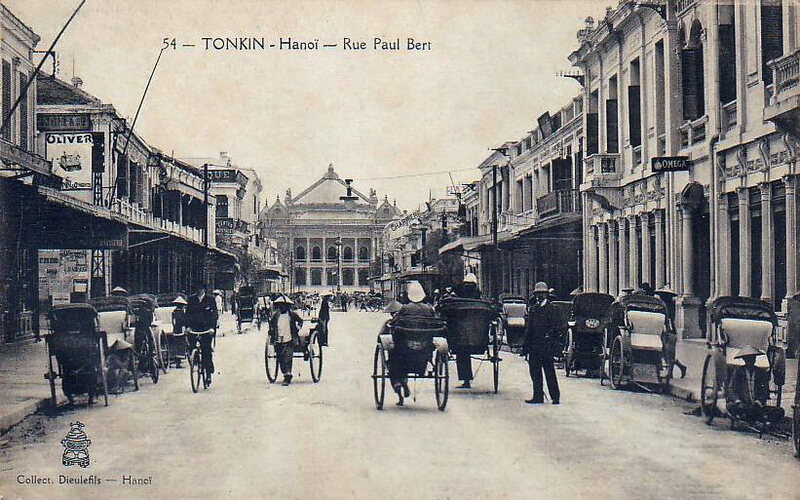

IN 1897, PAUL DOUMER ARRIVED in Hanoi, Vietnam. A 40-something French government worker fresh off a big professional failure—he resigned as minister of finance after his scheme for a new income tax failed—Doumer had a new job to try his hand at. He’d been appointed the Governor-General of French Indochina, a group of colonies in Southeast Asia that included what is now Vietnam.

Doumer set about outfitting Indochina—and especially Hanoi, the capital—with modern infrastructure befitting property of France. By the turn of the century, a typical colonist in Hanoi lived on a wide avenue lined with trees. Home was a spacious villa with many rooms and fine European things—including, notably, a toilet.

Ah, the toilet. What better way to distinguish French Hanoi, Doumer thought. The vast sewer system that ran under the French section of town—and the smaller one serving the overcrowded neighborhoods where the Vietnamese inhabitants lived—was a symbol of cleanliness and progress.

Imagine the dismay, then, when rats began emerging from the drains.

It turns out that when Doumer’s colonial government laid more than nine miles of sewage pipe beneath Hanoi, it inadvertently created nine miles of cool, dark rodent paradise, where the pests could breed without fear of predators. And when they got hungry, the rats had direct access to the city’s ritziest real estate via a subterranean superhighway. Under the streets of French Hanoi, rats multiplied exponentially—and then skittered to the surface.

As if it wasn’t enough that these furry invaders disrupted the colonists’ illusion of European tranquility in Asia, cases of the bubonic plague started popping up, and rats were suspected of carrying the disease. Something had to be done.

A solution was devised. Vietnamese rat hunters, hired by the colonial government, would descend into the sewers to hunt the rats down, and be paid for each one eliminated.

And so began The Great Hanoi Rat Massacre.

The bloodshed started swiftly. In the last week of April, 1902, 7,985 rats were killed—and that was just the beginning. The assassins continued to gain experience in the month of May, pushing the death toll above 4,000 each day. By the end of the month, the numbers were even more astounding. On May 30 alone, 15,041 rats met their end. In June, daily counts topped 10,000, and on June 21, the number was 20,112.

Let’s let that sink in: 20,112 rats killed in a single day.

Unfortunately, we don’t know exactly how the rats were killed—that detail has been lost to history. We only know about the rat hunt at all because in the ‘90s historian Michael Vann was in France, researching French colonialism, when he came upon a file labeled “Destruction of Animals: Rats.” Inside was some confusing, disorganized paperwork listing the number of rats exterminated in Hanoi around the turn of the century. The file was enticing–what on earth happened to these poor rats?—so Vann started working to piece together the full story.

Rat hunting wasn’t easy. Here’s an account from Vann’s paper on the rat massacre:

“One had to enter the dark and cramped sewer system, make one’s way through human waste in various forms of decay, and hunt down a relatively fierce wild animal which could be carrying fleas with the bubonic plague or other contagious diseases. This is not even to mention the probable existence of numerous other dangerous animals, such as snakes, spiders, and other creatures, that make this author’s skin crawl with anxiety.”

Eventually, the colonists realized that, even with this small army of paid rat killers, they were failing to make a dent in the rat population.

They proceeded to Plan B, offering any enterprising civilian the opportunity to get in on the hunt. A bounty was set—one cent per rat—and all you had to do to claim it was submit a rat’s tail to the municipal offices. That way, the government wouldn’t be overrun with bulky rat corpses. “I always think about that,” Dr. Vann says. “Who is the poor guy counting all these rat tails?”

The French were especially pleased with this arrangement because they’d been encouraging entrepreneurialism in Vietnam. And at first, it seemed to be working. Tails poured in. French ingenuity triumphed again.

But then there started to be curious sightings, all around town: Rats, alive and healthy, running around without their tails.

It turned out the hunters would rather amputate a live animal’s tail than take a healthy rat, capable of breeding and creating so many more rats—with those valuable tails—out of commission. There were also reports that some Vietnamese were smuggling foreign rats into the city. And then the final straw: Health inspectors discovered, in the countryside on the outskirts of Hanoi, pop-up farming operations dedicated to breeding rats.

Apparently this was not what the French meant by entrepreneurialism. The bounty was scrapped, and the city’s residents resigned themselves to coexisting with the pests.

The French were right about one thing, though: Those rats really were carrying bubonic plague. In 1906, with rats left to multiply in the sewers unchecked, there was an outbreak in Hanoi. At least 263 people died, most of them Vietnamese. Doumer, meanwhile, went home to France, where he was celebrated as the most effective Governor-General of Indochina to date. He went on to become president.

“It’s sort of a morality tale for the arrogance of modernity, that we put so much faith into science and reason and using industry to solve every problem,” Vann says. “This is the same kind of mindset that lead to World War I—the idea that the machine gun, because it kills so efficiently, is going to lead to a quick war. And what that actually lead to is a long war where many people lost their lives.”

These days, the Great Hanoi Rat Massacre is mostly cited as an example of the “Cobra Effect,” an economic theory about how incentives, in a complex system, can lead to perverse, unintended consequences. Sometimes, it’s trotted out as argument against government intervention of any kind—but Vann says that that kind of misses the point.

So what does he think the lesson is instead? “To watch out for programs being created in situations where where the arrogance is so strong and the power differential is so intense that evidence can be ignored.”

In 1997, Vann went to Vietnam to do archival research on the rat massacre. One day, he reached into the top drawer of a card catalogue dedicated to pre-1954 French-language files, and felt a rat scurry over his hand. Long after the French packed up and left Vietnam, the rats remain.

Đăng nhận xét