China and the future of Antarctica

Beijing rules out mining on the continent, but tourism and fishing could be concerns, writes Liu Nengye

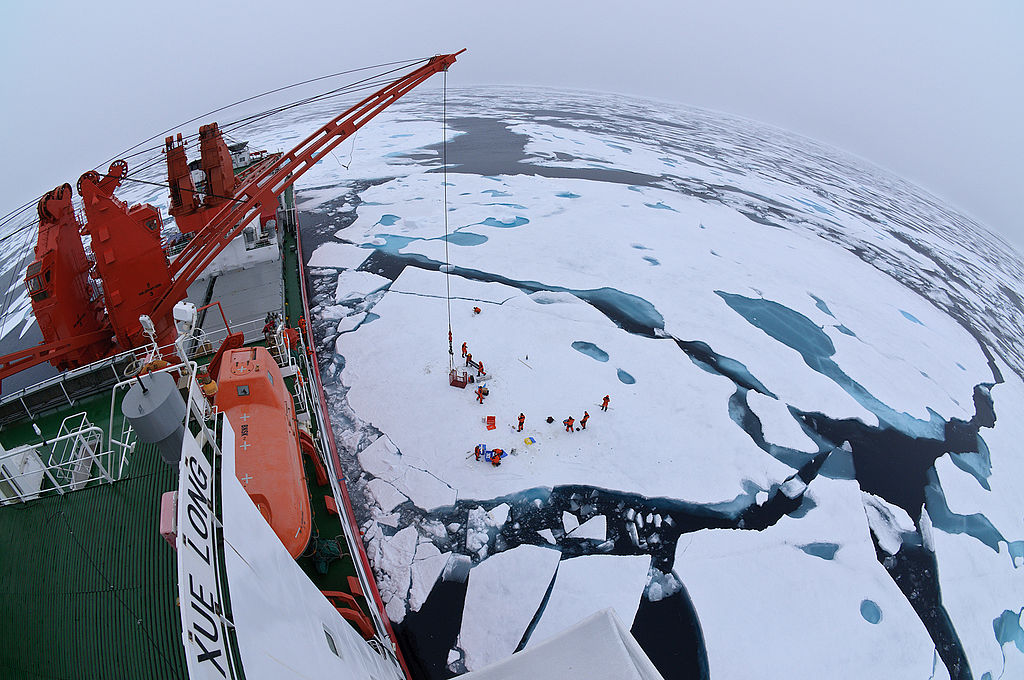

Arctic Ocean drift ice seen from Chinese icebreaker Xue Long (Snow Dragon) Image: Timo Palo

China hosted the 40th Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM) in Beijing from 22 May to 1 June, and for the first time in its history. The Antarctic and the Southern Ocean are governed by an extensive regime called the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS), and the annual meeting is for all member nations (or parties) of the treaty to discuss pressing issues.

Only consultative parties that have demonstrated their interest in Antarctica by “conducting substantial research activity there” can take part in decision-making processes. China became a consultative party in 1985 after the establishment of the Great Wall Station (its first research outpost in the region).

The 40th ATCM was a prime opportunity to observe China’s changing role in Antarctic governance and the meeting could be seen as a milestone in China’s engagement with the treaty system since it was adopted in 1958.

Though a latecomer, China has become a significant player in the system after a decades-long learning process, and its position matters greatly to the development of the region.

So how does China view the future of Antarctica?

China sees Antarctica as a “new frontier” possessing rich natural resources that are crucial for human development. To China, Antarctica is different from marine areas that are considered “core interests”, such as the South China Sea or Taiwan. In the new frontier, China’s objective is to cooperate with other countries to establish a governance regime that reflects China’s interests.

The ATS aims to achieve a balance between protection and peaceful use. At this year’s summit, China organised a special meeting that specifically discussed this issue.

China is interested in peaceful use of the Antarctic in line with Article 1 of the Antarctic Treaty. Examples of such usage include scientific research, tourism, bioprospecting, and fisheries in the Southern Ocean. Most issues were debated during the ATCM, while fisheries were a key focus of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources.

China’s 13th Five Year Plan (2016-2020) declared that the Chinese government will significantly invest in polar research through the Xue Long Tan Ji Project, a commitment that was reaffirmed in the White Paper “China’s Antarctic Activities”, published by the State Oceanic Administration during the 40th ATCM.

Since 2007, the number of Chinese tourists has continued to grow and now constitutes the second largest group of visitors to Antarctica. At the same time, Chinese fishing vessels have been fishing krill in the Southern Ocean since 2009. It is expected that the Chinese presence in the Antarctic will increase further in coming years.

Meanwhile, high-level Chinese officials have expressed concerns regarding increased Antarctic tourism. The China Tourism Bureau is also discouraging Chinese citizens from visiting Antarctica. Concern for safeguarding pristine parts of the region eventually drove China to support, albeit reluctantly at first, the establishment of a marine protected area in the Ross Sea.

Further, China has reiterated many times that it has no mining plan for the continent. Indeed, China ratified the Protocol on the Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (“the Madrid Protocol”) that completely bans mining. As a country that is keen to take the lead on global governance issues, such as combatting climate change, China would be highly unlikely to openly violate its international obligation under the ATS.

China could and should have a say about what the appropriate balance of protection and use should be in Antarctica. Nevertheless, one country alone cannot determine the future of Antarctica. In the era of the Anthropocene, all countries must work together to agree on the “balance”. China’s best Antarctic strategy would be to enshrine the stability of the treaty system, while trying to shape it to meet national interests.

Only consultative parties that have demonstrated their interest in Antarctica by “conducting substantial research activity there” can take part in decision-making processes. China became a consultative party in 1985 after the establishment of the Great Wall Station (its first research outpost in the region).

The 40th ATCM was a prime opportunity to observe China’s changing role in Antarctic governance and the meeting could be seen as a milestone in China’s engagement with the treaty system since it was adopted in 1958.

Though a latecomer, China has become a significant player in the system after a decades-long learning process, and its position matters greatly to the development of the region.

So how does China view the future of Antarctica?

China sees Antarctica as a “new frontier” possessing rich natural resources that are crucial for human development. To China, Antarctica is different from marine areas that are considered “core interests”, such as the South China Sea or Taiwan. In the new frontier, China’s objective is to cooperate with other countries to establish a governance regime that reflects China’s interests.

The ATS aims to achieve a balance between protection and peaceful use. At this year’s summit, China organised a special meeting that specifically discussed this issue.

China is interested in peaceful use of the Antarctic in line with Article 1 of the Antarctic Treaty. Examples of such usage include scientific research, tourism, bioprospecting, and fisheries in the Southern Ocean. Most issues were debated during the ATCM, while fisheries were a key focus of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources.

China’s 13th Five Year Plan (2016-2020) declared that the Chinese government will significantly invest in polar research through the Xue Long Tan Ji Project, a commitment that was reaffirmed in the White Paper “China’s Antarctic Activities”, published by the State Oceanic Administration during the 40th ATCM.

Since 2007, the number of Chinese tourists has continued to grow and now constitutes the second largest group of visitors to Antarctica. At the same time, Chinese fishing vessels have been fishing krill in the Southern Ocean since 2009. It is expected that the Chinese presence in the Antarctic will increase further in coming years.

Meanwhile, high-level Chinese officials have expressed concerns regarding increased Antarctic tourism. The China Tourism Bureau is also discouraging Chinese citizens from visiting Antarctica. Concern for safeguarding pristine parts of the region eventually drove China to support, albeit reluctantly at first, the establishment of a marine protected area in the Ross Sea.

Further, China has reiterated many times that it has no mining plan for the continent. Indeed, China ratified the Protocol on the Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (“the Madrid Protocol”) that completely bans mining. As a country that is keen to take the lead on global governance issues, such as combatting climate change, China would be highly unlikely to openly violate its international obligation under the ATS.

China could and should have a say about what the appropriate balance of protection and use should be in Antarctica. Nevertheless, one country alone cannot determine the future of Antarctica. In the era of the Anthropocene, all countries must work together to agree on the “balance”. China’s best Antarctic strategy would be to enshrine the stability of the treaty system, while trying to shape it to meet national interests.

Đăng nhận xét