December 8, 2021

Tiger sharks sometimes swim thousands of kilometers—far enough to move among oceans. Their flexible diets and adaptable behaviors set them up to be successful jet-setters, zipping around the world and mingling with far-flung members of tiger shark society.

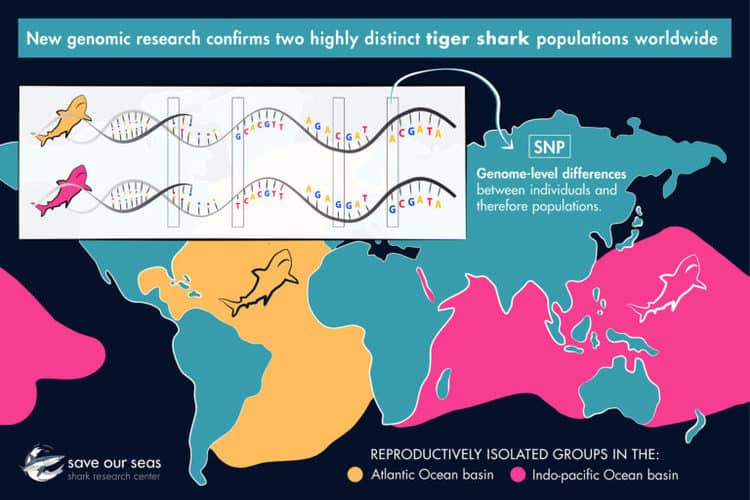

But new research shows that tiger sharks from different ocean regions aren’t as chummy with one another as expected. In fact, tiger sharks in the Atlantic and Indo-Pacific basins have diverged into at least two genetically distinct groups, according to a recent report in the Journal of Heredity.

A team of scientists from the Save Our Seas Foundation’s Shark Research Center at Nova Southeastern University in Dania Beach, Florida, compared the genomes of 242 tiger sharks from 10 locations around the world. The authors, led by marine biologist Andrea Bernard, analyzed small genetic markers scattered throughout the tiger shark genome.

Their results exposed many contrasting markers between Atlantic tiger sharks and their Indo-Pacific counterparts. The researchers anticipated some differences based on their preliminary analysis of these sharks in 2016, but they found even more variation than expected.

“If this differentiation continues over time, these groups will be on their way to speciation,” said senior author Mahmood Shivji, director of the foundation’s Shark Research Center. “But they’re not there yet, at least in our opinion.”

Tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier) are sleek, stripy apex predators that can grow more than 5 meters long. They aren’t picky eaters; their prey includes fish, turtles, seabirds, snakes, dolphins and other sharks.

Tiger sharks seem content whether they’re gliding through the open ocean, hunting in meter-deep water close to shore or cruising coral reefs. “I honestly can’t think of any other shark that does that,” Shivji said. But fishing bycatch and the fin trade have made these versatile predators a Near Threatened species, according to the IUCN.

Despite their long voyages, tiger sharks seem to be homebodies when it comes to breeding. “I’m not really shocked by the results,” said marine biologist Chris Lowe, director of the Shark Lab at California State University, Long Beach. Lowe noted that researchers still don’t know why tiger sharks travel so far or how climate change may affect their movements.

Scientists haven’t observed physical or behavioral distinctions between the Atlantic and Indo-Pacific populations, but they haven’t had reasons to look so closely. “Tiger sharks are just these big things with stripes on them,” Shivji said. “Why would anybody even think they might be two different groups?”

Now, ecologists have a reason to look for different traits or behaviors between the two groups. And conservationists can develop fishery policies to protect sharks in both populations.

A third group with more subtle variations also emerged: tiger sharks around the long chain of the Hawaiian Islands.

“Luckily, much of the Hawaiian archipelago is protected,” Shivji said. “But these tiger sharks don’t know that. They can travel huge distances and they’re getting well outside of the protective boundaries.”

Next, the group wants to perform whole-genome sequencing to get a better idea of how the shark populations differ. They also want to use the current analysis to compare tiger shark with their evolutionary cousins, like silky sharks or sandbar sharks.

Lowe said he looks forward to seeing this kind of global, high-resolution genetics study applied to other species. He believes it could inform fisheries management and conservation in the future.

“Tiger sharks have captured my imagination because phylogenetically they’re a real oddball,” Shivji said. Understanding the genetic origins of their idiosyncratic charm may make the importance of protecting them even clearer.

Citation:

Bernard, A. N., Finnegan, K. A., Pavinski Bitar, P., Stanhope, M. J., Shivji, M. S. (2021). Genomic assessment of global population structure in a highly migratory and habitat versatile apex predator, the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier). Journal of Heredity, 112 (6), 497-501. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esab046

This article by Graycen Wheeler was first published by Mongabay.com on 30 November 2021. Lead Image: Large tiger sharks overwinter in the Bahamas and migrate thousands of kilometers into open ocean in the summer, but they remain in the Atlantic. Photo credit: © Christopher Vaughan-Jones.

What you can do

Support ‘Fighting for Wildlife’ by donating as little as $1 – It only takes a minute. Thank you.

Fighting for Wildlife supports approved wildlife conservation organizations, which spend at least 80 percent of the money they raise on actual fieldwork, rather than administration and fundraising. When making a donation you can designate for which type of initiative it should be used – wildlife, oceans, forests or climate.

(Sources: Focusing on Wildlife)

Đăng nhận xét