Formerly sweeping policies are now being tailored, with blanket factory closures out, and some businesses and centralised heating systems now free to burn coal

Handan city, Hebei, in 2019 (Image: Alamy)

Zhao Cheng, 54, owns a small rubber factory in Shaanxi province. He’s been in the trade for 20 years. “Nowadays we’re working intermittently because of environment protection,” he says. “Last winter we had to get factories in Nanjing and Wuxi to help us fulfil orders or we’d have lost the customers.”

Zhao’s work has been badly affected by various environmental orders designed to curb industrial pollution. Local governments in Hebei and Shanxi have also taken drastic measures to tackle smog.

China first set of smog-reduction targets, for 2013-17, focussed on its three biggest city clusters: Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, the Pearl river delta and the Yangtze delta. Those targets, which included a 33% reduction in Beijing of average fine particle pollution (PM2.5), were easily achieved.

The tough measures taken, and their impact on businesses have been coming under the microscope of public opinion, all while the government tries to “fine tune” its policies.

Bringing up the rear

The Fen-Wei plain is a key battleground in China’s war on smog. Comprising the Fen and Wei river plains, both parts of the Yellow river basin, it includes sections of the central provinces Shaanxi, Shanxi and Henan, notably the city of Xi’an.

The area was only brought within the scope of government anti-smog efforts in 2018, when, in an air pollution action plan, it replaced the Pearl river delta. Air pollution clean-up efforts here lag 5-6 years behind other regions, according to Liu Bingjiang, of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE). In 2018, average PM2.5 was 58 micrograms per cubic metre, just 5% less than 2015. When the MEE released air pollution rankings for 169 key Chinese cities in 2018, six of the Fen-Wei plane’s 11 prefecture-level cities placed in the bottom 20.

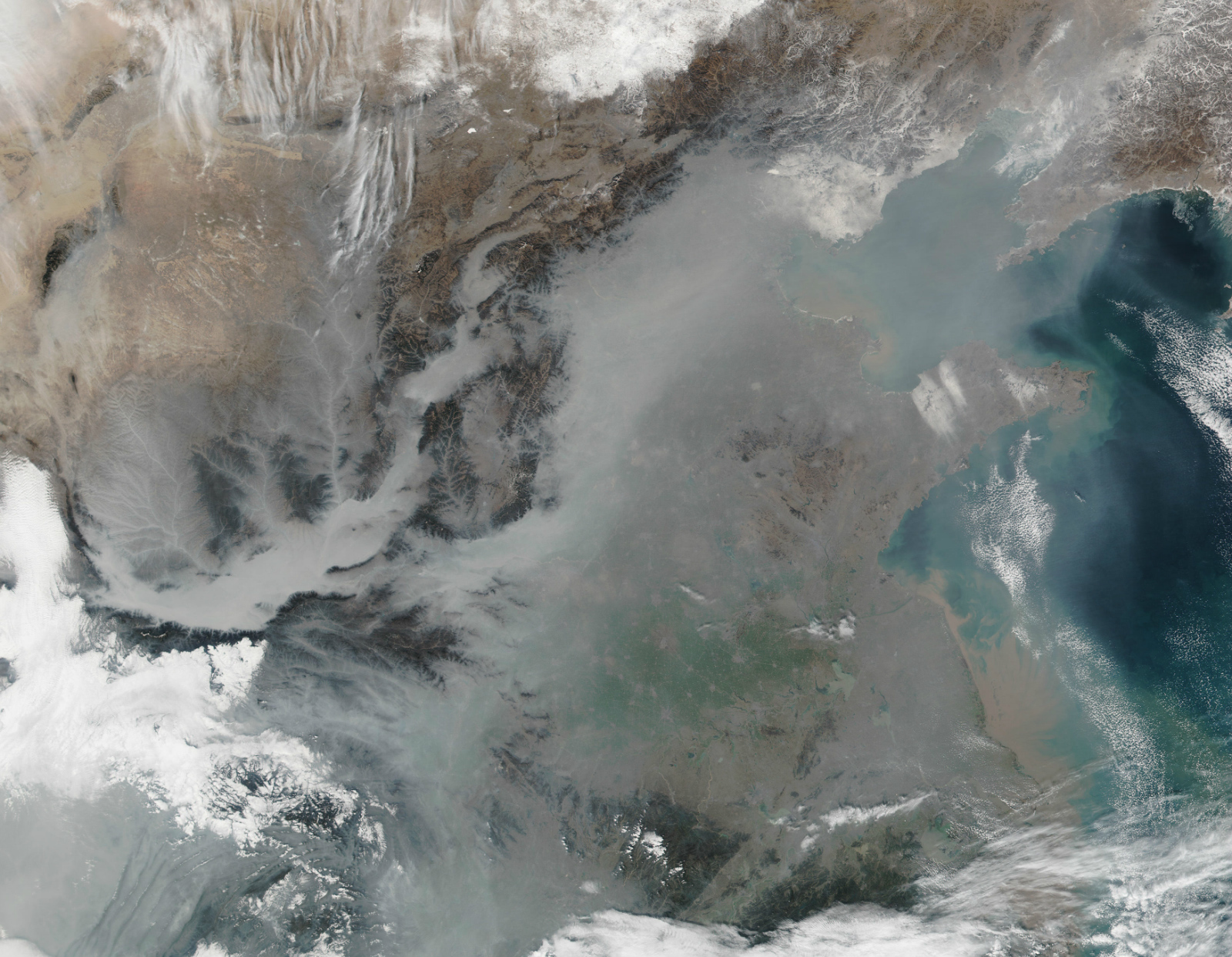

Thick haze over north-eastern and central China (Image: Alamy)

Fu Lu, China director for Clean Air Asia, put gave the city of Linfen as an example. City officials have repeatedly been summoned by the MEE for failures to tackle pollution, breaching regulations and even faking data. “Overall, the Fen-Wei plain is far behind other regions, in terms of effort put in and results achieved.”

Zhao Cheng disagrees that industry hasn’t been trying hard enough. He says central government inspectors, accompanied by village cadres, came in the summer of 2019 to halt work and seal up equipment and buildings. “The price of rubber and concrete has increased threefold because the producers have been told to stop work. We’ve no choice but to look for alternative ways of making money while we wait and see if the environmental restrictions ease off.”

The Fen-Wei plain is home to much heavy industry: aluminium smelters, coking plants, steel mills and coal-to-chemical plants. These tend to be smaller businesses with poor-quality equipment; the majority are unable to meet emissions standards consistently. Quick, fair solutions are hard to come by.

Zou Ji, CEO and president of Energy Foundation China, says that for several years environmental policies have been imposed “at any price”. This has greatly improved air quality, but at enormous cost. “The next stage of tackling smog needs ‘good-quality’ growth, which sudden crackdowns can’t achieve, or at least not at an acceptable price.”

The end of one-size-fits all?

Because of the controversy over anti-smog measures, in 2019 the environmental authorities said repeatedly they should not be imposed in a one-size-fits-all manner.

MEE spokesperson Liu Youbing said: “Imposing a uniform approach harms the image and credibility of Party and government, as well as the legitimate rights of firms operating legally, and threatens normal environmental protection efforts.” He also stressed that the length, fairness and achievability of anti-smog measures for autumn and winter 2019-2020 had been carefully considered.

Unlike in 2018, the 2019-2020 measures do not include mandatory blanket factory closures. Instead, emergency measures for days of severe pollution have been tailored for each of the three smog-control regions.

Firms are graded A, B or C according to production methods, level of pollution and emissions intensity. Grade C firms are subject to the original emergency measures including forced closures. Grade B firms (provincial leaders) have to take some measures. Grade A firms (national leaders) do not have to take any extra measures.

The Fen-Wei plain produces and consumes a lot of coal. It accounts for almost 90% of the region’s energy, compared to 60% nationwide, and that makes the green energy transition particularly challenging.

According to Zhao Cheng, reducing the small-scale burning of coal has forced villagers to close down chicken and pig farms, vinegar-making facilities and even grain dryers that rely on coal.

Gas was to replace coal but a subsequent nationwide shortage added to concerns that the transition was moving too quickly. In the response, the government eased some demands for 2019’s smog plan: there was no requirement to increase coal-to-gas conversions if the infrastructure and safety assurances were not yet in place.

Government officials and documents since 2018 have raised the possibility of using coal when it is deemed most appropriate. This is a departure from 2017, when bans on small-scale coal use for domestic heating, or outright bans on coal use, were put in place. By 2018, though, northern cities applying for clean-heating trial city status were permitted to use “clean coal” as a heating source.

At a recent National Energy Commission meeting, premier Li Keqiang reiterated that electricity, gas and coal may all be acceptable, in the right context. Some say this policy, with no strict curbs on coal-use for winter heating, indicates a more practical approach to heating.

Smog in Anyang city, Henan province (Image: Alamy)

New approach, new challenges

These more flexible approaches have been widely seen as a weakening of anti-smog efforts. Zhu Tong, of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, thinks that what is being called “fine-tuning” is actually a return to coal burning – a step backwards, rather than an advance.

However, Jin Ling, a researcher at the MEE, says small-scale, polluting coal burning is still banned. She says only centralised heating systems that meet national emissions standards, with heat being distributed to consumers via pipe networks, are being permitted.

There is a lack of consensus on the definition of “clean coal”, and a lack of regulation on its production, transport and emissions; oversight is particularly hard in rural areas. Some experts would rather see a continued ban on coal use, with time allowed for full compliance and so a slower transition to gas or electricity, than permission being granted for some coal burning and no phaseout timeline. Ruan Lijun, of the China Coal Processing and Utilisation Association, says that coal can only be described as “clean” under certain conditions, depending on furnace type, burn method and emissions standards.

The government has been subsidising the alternatives. Xie Honghao, head of the Xi’an Energy Saving Association, said that local governments’ main concern is that the gradual removal of clean-heating subsidies will invite pressure to return to coal. Shaanxi received 1.28 billion yuan (US$180 million) in funding for clean heating trials in 2019, and Shanxi and Henan, are also eligible for central government support.

The “graded” management of businesses will also face practical challenges.

One industry insider says many large firms are applying for Grade A status, but the process is unclear and they are failing to get the expected exemptions, despite meeting the requirements.

More confusing still is policy direction. The same insider said that predictability is vital for businesses. Investment in environmental equipment is expensive, and companies don’t want to spend the money if they can’t be sure they’ll be able to keep working.

Zhao Cheng says he won’t be making any additions to his factory. “For us small companies, with output worth hundreds of thousands [of yuan] a year, new equipment costing millions is no use.”

Zou Ji thinks the key task now is to reassure companies and ensure they aren’t affected by talk of slacker regulations or a return to coal. The government needs a policy framework for the next five to ten years, setting clear expectations for businesses and indicating that environmental policies will only be getting tougher. That will give local governments and heavy industry time to make changes or pull out, he said.

“More important than end-of-pipe controls are changes to the energy mix, the industrial structure, transport and land use,” Zou said.

Now more than ever…

chinadialogue is at the heart of the battle for truth on climate change and its challenges at this critical time.

Our readers are valued by us and now, for the first time, we are asking for your support to help maintain the rigorous, honest reporting and analysis on climate change that you value in a 'post-truth' era.

Support chinadialogue

Đăng nhận xét