The rise of Modi and the Hindu far right.

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) workers participate in a rally in Guwahati on January 21, 2018. (AFP via Getty Images / Biju Boro)

While protest reverberates on the streets of Chile, Catalonia, Bolivia, Britain, France, Iraq, Lebanon, and Hong Kong, and a new generation rages against what has been done to their planet, I hope you will forgive me for speaking about a place where the street has been taken over by something quite different. There was a time when dissent was India’s best export. But now, even as protest swells in the West, our great anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist movements for social and environmental justice—the marches against big dams, against the privatization and plunder of our rivers and forests, against mass displacement and the alienation of indigenous peoples’ homelands—have largely fallen silent. On September 17 this year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi gifted himself the filled-to-the-brim reservoir of the Sardar Sarovar Dam on the Narmada River for his 69th birthday, while thousands of villagers who had fought that dam for more than 30 years watched their homes disappear under the rising water. It was a moment of great symbolism.

In India today, a shadow world is creeping up on us in broad daylight. It is becoming more and more difficult to communicate the scale of the crisis even to ourselves. An accurate description runs the risk of sounding like hyperbole. And so, for the sake of credibility and good manners, we groom the creature that has sunk its teeth into us—we comb out its hair and wipe its dripping jaw to make it more personable in polite company. India isn’t by any means the worst, or most dangerous, place in the world—at least not yet—but perhaps the divergence between what it could have been and what it has become makes it the most tragic.

Right now, 7 million people in the valley of Kashmir, overwhelming numbers of whom do not wish to be citizens of India and have fought for decades for their right to self-determination, are locked down under a digital siege and the densest military occupation in the world. Simultaneously, in the eastern state of Assam, almost two million people who long to belong to India have found their names missing from the National Register of Citizens (NRC), and risk being declared stateless. The Indian government has announced its intention of extending the NRC to the rest of India. Legislation is on its way. This could lead to the manufacture of statelessness on a scale previously unknown.

The rich in Western countries are making their own arrangements for the coming climate calamity. They’re building bunkers and stocking reservoirs of food and clean water. In poor countries—India, despite being the fifth-largest economy in the world, is, shamefully, still a poor and hungry country—different kinds of arrangements are being made. The Indian government’s August 5, 2019, annexation of Kashmir has as much to do with the Indian government’s urgency to secure access to the five rivers that run through the state of Jammu and Kashmir as it does with anything else. And the NRC, which will create a system of tiered citizenship in which some citizens have more rights than others, is also a preparation for a time when resources become scarce. Citizenship, as Hannah Arendt famously said, is the right to have rights.

The dismantling of the idea of liberty, fraternity, and equality will be—in fact already is—the first casualty of the climate crisis. I’m going to try to explain in some detail how this is happening. And how, in India, the modern management system that emerged to handle this very modern crisis has its roots in an odious, dangerous filament of our history.

The violence of inclusion and the violence of exclusion are precursors of a convulsion that could alter the foundations of India—and rearrange its meaning and its place in the world. Our Constitution calls India a “socialist secular democratic republic.” We use the word “secular” in a slightly different sense from the rest of the world—for us, it’s code for a society in which all religions have equal standing in the eyes of the law. In practice, India has been neither secular nor socialist. It has always functioned as an upper-caste Hindu state. But the conceit of secularism, hypocritical though it may be, is the only shard of coherence that makes India possible. That hypocrisy was the best thing we had. Without it, India will end.

In his May 2019 victory speech, after his party won a second term, Modi boasted that no politicians from any political party had dared to campaign on “secularism.” The tank of secularism, Modi seemed to say, was now empty. So, it’s official. India is running on empty. And we are learning, too late, to cherish hypocrisy. Because with it comes a vestige, a pretense at least, of remembered decency.

The violence of inclusion and the violence of exclusion are precursors of a convulsion that could alter the foundations of India—and rearrange its meaning and its place in the world. Our Constitution calls India a “socialist secular democratic republic.” We use the word “secular” in a slightly different sense from the rest of the world—for us, it’s code for a society in which all religions have equal standing in the eyes of the law. In practice, India has been neither secular nor socialist. It has always functioned as an upper-caste Hindu state. But the conceit of secularism, hypocritical though it may be, is the only shard of coherence that makes India possible. That hypocrisy was the best thing we had. Without it, India will end.

In his May 2019 victory speech, after his party won a second term, Modi boasted that no politicians from any political party had dared to campaign on “secularism.” The tank of secularism, Modi seemed to say, was now empty. So, it’s official. India is running on empty. And we are learning, too late, to cherish hypocrisy. Because with it comes a vestige, a pretense at least, of remembered decency.

But what was bad for the country turned out to be excellent for the BJP. Between 2016 and 2017, even as the economy tanked, it became one of the richest political parties in the world. Its income increased by 81 percent, making it nearly five times richer than its main rival, the Congress Party, whose income declined by 14 percent. Smaller political parties were virtually bankrupted. This war chest won the BJP crucial state elections in Uttar Pradesh, and turned the 2019 general election into a race between a Ferrari and a few old bicycles. And since elections are increasingly about money, the chances of a free and fair election in the near future seem remote. So maybe demonetization was not a blunder after all.

During Modi’s second term, the RSS has stepped up its game. No longer a shadow state or a parallel state, it is the state. Day by day, we see examples of its control over the media, the police, the intelligence agencies. Worryingly, it appears to exercise considerable influence over the armed forces, too. Foreign diplomats and ambassadors have been hobnobbing with Mohan Bhagwat. The German ambassador even trooped all the way to the RSS headquarters in Nagpur to pay his respects.

In truth, things have reached a stage where overt control is no longer even necessary. More than four hundred round-the-clock television news channels, millions of WhatsApp groups and TikTok videos keep the population on a drip feed of frenzied bigotry.

This November the Supreme Court of India ruled on what one judge called one of the most important cases in the world. On December 6, 1992, in the town of Ayodhya, a Hindu vigilante mob, organized by the BJP and the Vishwa Hindu Parishad—the World Hindu Council—literally hammered a 460-year-old mosque into dust. They claimed that this mosque, the Babri Masjid, was built on the ruins of a Hindu temple that had marked the birthplace of Lord Ram. More than 2,000 people, mostly Muslims, were killed in the communal violence that followed. In its recent judgment, the court held that Muslims could not prove their exclusive and continuous possession of the site. Instead, it turned the site over to a trust—to be constituted by the BJP government—tasked with building a Hindu temple on it. There have been mass arrests of people who have criticized the judgment. The VHP has refused to back down on its past statements that it will turn its attention to other mosques. This can be an endless campaign—after all, everything is built over something.

With the influence that immense wealth generates, the BJP has managed to co-opt, buy out, or simply crush its political rivals. The hardest blow has fallen on the parties with bases among the Dalit and other disadvantaged castes in the northern states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Many of their traditional voters have deserted these parties—the Bahujan Samaj Party, Rashriya Janata Dal, and Samajwadi Party—and migrated to the BJP. To achieve this feat—and it is nothing short of a feat—the BJP worked hard to exploit and expose the hierarchies within the Dalit and disadvantaged castes, which have their own internal universe of hegemony and marginalization. The BJP’s overflowing coffers, and its deep, cunning understanding of caste have completely altered the conventional electoral math.

Having secured Dalit and disadvantaged-caste votes, the BJP’s policies of privatizing education and the public sector are rapidly reversing the gains made by affirmative action—known in India as “reservation”—pushing those who belong to disadvantaged castes out of jobs and educational institutions. Meanwhile, the National Crime Records Bureau shows a sharp increase of atrocities against Dalits, including lynchings and public floggings. This September, while Modi was being honored by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for building toilets, two Dalit children, whose home was just the shelter of a plastic sheet, were beaten to death for shitting in the open. To honor a prime minister for his work on sanitation while tens of thousands of Dalits continue to work as manual scavengers—carrying human excreta on their heads—is grotesque.

What we are living through now, in addition to the overt attack on religious minorities, is an aggravated class and caste war.

To consolidate their political gains, the RSS and BJP’s main strategy is to generate long-lasting chaos on an industrial scale. They have stocked their kitchen with a set of simmering cauldrons that can, whenever necessary, be quickly brought to the boil.

On August 5, 2019, the Indian government unilaterally breached the fundamental conditions of the Instrument of Accession by which the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir agreed to become part of India in 1947. It stripped Jammu and Kashmir of statehood and its special status—which included its right to have its own constitution and its own flag. The dissolution of the legal entity of the state also meant the dissolution of Section 35A of the Indian Constitution, which secured the erstwhile state’s residents the rights and privileges that made them stewards of their own territory. In preparation for the move, the government flew in more than 80,000 troops to supplement the hundreds of thousands already stationed there. By the night of August 4, tourists and pilgrims had been evacuated from the Kashmir Valley. Schools and markets were shut down. By midnight, the Internet was cut and phones went dead. In the weeks that followed, more than 4,000 people were arrested: politicians, businessmen, lawyers, rights activists, local leaders, students, and three former chief ministers. Kashmir’s entire political class, including those who have been loyal to India, was incarcerated.

The abrogation of Kashmir’s special status, the promise of an all-India National Register of Citizens, the building of the Ram temple in Ayodhya—are all on the front burners of the RSS and BJP kitchen. To reignite flagging passions, all they need to do is to pick a villain from their gallery and unleash the dogs of war. There are several categories of villains—Pakistani jihadis, Kashmiri terrorists, Bangladeshi “infiltrators,” or any one of a population of nearly 200 million Indian Muslims who can always be accused of being Pakistan-lovers or anti-national traitors. Each of these “cards” is held hostage to the other, and often made to stand in for the other. They have little to do with each other, and are often hostile to each other because their needs, desires, ideologies, and situations are not just inimical, but end up posing an existential threat to each other. Simply because they are all Muslim, they each have to suffer the consequences of the others’ actions.

In two national elections now, the BJP has shown that it can win a majority in parliament without the “Muslim vote.” As a result, Indian Muslims have been effectively disenfranchised, and are becoming that most vulnerable of people—a community without political representation, without a voice. Various forms of vicious social boycott are pushing them down the economic ladder, and, for reasons of physical security, into ghettos. Indian Muslims have also lost their place in the mainstream media—the only Muslim voices we hear on television shows are the absurd few who are constantly and deliberately invited to play the part of the primitive Islamist, to make things worse than they already are. Other than that, the only acceptable public speech for the Muslim community is to constantly reiterate and demonstrate its loyalty to the Indian flag. So, while Kashmiris, brutalized as they are because of their history and, more importantly, their geography, still have a lifeboat—the dream of azadi, of freedom—Indian Muslims have to stay on deck to help fix the broken ship.

(There is another category of “anti-national” villain—human rights activists, lawyers, students, academics, “urban Maoists”—who have been defamed, jailed, embroiled in legal cases, snooped on by Israeli spyware, and, in several instances, assassinated. But that’s a whole other deck of cards.)

The lynching of Tabrez Ansari illustrates just how broken the ship is, and how deep the rot. Lynching, as you in the United States well know, is a public performance of ritualized murder, in which a man or woman is killed to remind their community that it lives at the mercy of the mob. And that the police, the law, the government—as well as the good people in their homes, who wouldn’t hurt a fly, who go to work and take care of their families—are all friends of the mob. Tabrez was lynched this June. He was an orphan, raised by his uncles in the state of Jharkhand. As a teenager, he went away to the city of Pune, where he found a job as a welder. When he turned 22, he returned home to get married. The day after his wedding to 18-year-old Shahista, Tabrez was caught by a mob, tied to a lamppost, beaten for hours and forced to chant the new Hindu war cry, “Jai Shri Ram!”—Victory to Lord Ram! The police eventually took Tabrez into custody but refused to allow his distraught family and young bride to take him to the hospital. Instead, they accused him of being a thief, and produced him before a magistrate, who sent him back to custody. He died there four days later.

A resident of Marichakandi Char holds up his identity cards and the waterproof folder that holds his “legacy” papers. (Sanjay Kak)

In its latest report, released earlier this month, the National Crime Records Bureau has carefully left out data on mob lynchings. According to the Indian news site The Quint, there have been 113 deaths by mob violence since 2015. Lynchers, and others accused in hate crimes including mass murder have been rewarded with public office and honored by ministers in Modi’s cabinet. Modi himself, usually garrulous on Twitter, generous with condolences and birthday greetings, goes very quiet each time a person is lynched. Perhaps it’s unreasonable to expect a prime minister to comment every time a dog comes under the wheels of someone’s car. Particularly since it happens so often.

Here in the United States, on September 22, 2019—five days after Modi’s birthday party at the Narmada dam site—50,000 Indian Americans gathered in the NRG Stadium in Houston. The “Howdy, Modi!” extravaganza there has already become the stuff of urban legend. President Donald Trump was gracious enough to allow a visiting prime minister to introduce him as a special guest in his own country, to his own citizens. Several members of the US Congress spoke, their smiles too wide, their bodies arranged in attitudes of ingratiation. Over a crescendo of drumrolls and wild cheering, the adoring crowd chanted, “Modi! Modi! Modi!” At the end of the show, Trump and Modi linked hands and did a victory lap. The stadium exploded. In India, the noise was amplified a thousand times over by carpet coverage on television channels. “Howdy” became a Hindi word. Meanwhile, news organizations ignored the thousands of people protesting outside the stadium.

US President Donald Trump and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi during a “Howdy, Modi” rally celebrating Modi at NRG Stadium in Houston, Texas. (Reuters / Daniel Kramer)

Not all the roaring of the 50,000 in the Houston stadium could mask the deafening silence from Kashmir. That day, September 22, marked the 48th day of curfew and communication blockade in the valley.

Once again, Modi has managed to unleash his unique brand of cruelty on a scale unheard of in modern times. And, once again, it has endeared him further to his loyal public. When the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Bill was passed in India’s parliament on August 6 there were celebrations across the political spectrum. Sweets were distributed in offices, and there was dancing in the streets. A conquest—a colonial annexation, another triumph for the Hindu Nation—was being celebrated. Once again, the conquerors’ eyes fell on the two primeval trophies of conquest—women and land. Statements by senior BJP politicians, and patriotic pop music videos that notched up millions of views, legitimized this indecency. Google Trends showed a surge in searches for the phrases “marry a Kashmiri girl” and “buy land in Kashmir.”

It was not all limited to loutish searches on Google. In the weeks after the siege, the Forest Advisory Committee cleared 125 projects that involve the diversion of forest land for other uses.

In the early days of the lockdown, little news came out of the valley. The Indian media told us what the government wanted us to hear. The heavily censored Kashmiri papers carried pages and pages of news about cancelled weddings, the effects of climate change, the conservation of lakes and wildlife sanctuaries, tips on how to live with diabetes and front-page government advertisements about the benefits that Kashmir’s new, downgraded legal status would bring to the Kashmiri people. Those “benefits” are likely to include projects that control and commandeer the water from the rivers that flow through Kashmir. They will certainly include the erosion that results from deforestation, the destruction of the fragile Himalayan ecosystem, and the plunder of Kashmir’s bountiful natural wealth by Indian corporations.

Real reporting about ordinary peoples’ lives came mostly from the journalists and photographers working for the international media—Agence France-Presse, the Associated Press, Al Jazeera, The Guardian, the BBC, The New York Times, and The Washington Post. The reporters, mostly Kashmiris, working in an information vacuum, with none of the tools usually available to modern-day reporters, traveled through their homeland at great risk to themselves, to bring us the news. And the news was of nighttime raids, of young men being rounded up and beaten for hours, their screams broadcast on public-address systems for their neighbors and families to hear, of soldiers entering villagers’ homes and mixing fertilizer and kerosene into their winter food stocks. The news was of teenagers with their bodies peppered with shotgun pellets being treated at home, because they would be arrested if they went to a hospital. The news was of hundreds of children being whisked away in the dead of night, of parents debilitated by desperation and anxiety. The news was of fear and anger, depression, confusion, steely resolve, and incandescent resistance.

But the home minister, Amit Shah, said that the siege only existed in peoples’ imaginations; the governor of Jammu and Kashmir, Satya Pal Malik, said phone lines were not important for Kashmiris and were only used by terrorists; and the army chief, Bipin Rawat, said, “Normal life in Jammu and Kashmir has not been affected. People are doing their necessary work.… Those who feel that life has been affected are the ones whose survival depends on terrorism.” It isn’t hard to work out who exactly the government of India sees as terrorists.

Imagine if all of New York City were put under an information lockdown and a curfew managed by hundreds of thousands of soldiers. Imagine the streets of your city remapped by razor wire and torture centers. Imagine if mini–Abu Ghraibs appeared in your neighborhoods. Imagine thousands of you being arrested and your families not knowing where you have been taken. Imagine not being able to communicate with anybody—not your neighbor, not your loved ones outside the city, no one in the outside world—for weeks together. Imagine banks and schools being closed, children locked into their homes. Imagine your parent, sibling, partner, or child dying and you not knowing about it for weeks. Imagine the medical emergencies, the mental health emergencies, the legal emergencies, the shortages of food, money, gasoline. Imagine being a day laborer or a contract worker, earning nothing for weeks on end. And then imagine being told that all of this was for your own good.

The horror that Kashmiris have endured over the last few months comes on top of the trauma of a 30-year-old armed conflict that has already taken 70,000 lives and covered their valley with graves. They have held out while everything was thrown at them—war, money, torture, mass disappearance, an army of more than a half million soldiers, and a smear campaign in which an entire population has been portrayed as murderous fundamentalists.

The siege has lasted for more than four months now. Kashmiri leaders are still in jail. They were offered release under the condition of agreeing not to make public statements about Kashmir for a whole year. Most have refused.

Now, the curfew has been eased, schools have been reopened and some phone lines have been restored. “Normalcy” has been declared. In Kashmir, normalcy is always a declaration—a fiat issued by the government or the army. It has little to do with people’s daily lives.

So far, Kashmiris have refused to accept this new normalcy. Classrooms are empty, streets are deserted and the valley’s bumper apple crop is rotting in the orchards. What could be harder for a parent or a farmer to endure? The imminent annihilation of their very identity, perhaps.

The new phase of the Kashmir conflict has already begun. Militants have warned that, from now on, all Indians will be considered legitimate targets. More than ten people, mostly poor, non-Kashmiri migrant workers, have been killed. (Yes, it’s the poor, almost always the poor, who get caught in the line of fire.) It is going to get ugly. Very ugly.

Soon all this recent history will be forgotten, and once again there will be debates in television studios that create an equivalence between atrocities by Indian security forces and Kashmiri militants. Speak of Kashmir, and the Indian government and its media will immediately tell you about Pakistan, deliberately conflating the misdeeds of a hostile foreign state with the democratic aspirations of ordinary people living under a military occupation. The Indian government has made it clear that the only option for Kashmiris is complete capitulation, that no form of resistance is acceptable—violent, nonviolent, spoken, written, or sung. Yet Kashmiris know that to exist, they must resist.

Why should they want to be a part of India? For what earthly reason? If freedom is what they want, freedom is what they should have.

It’s what Indians should want, too. Not on behalf of Kashmiris, but for their own sake. The atrocity being committed in their name involves a form of corrosion that India will not survive. Kashmir may not defeat India, but it will consume India. In many ways, it already has.

Rank and file: Over 200,000 RSS volunteers from Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh gather in Meerut in February 2018. (AFP via Getty Images / Sajjad Hussain)

This may not have mattered all that much to the 50,000 cheering in the Houston stadium, living out the ultimate Indian dream of having made it to America. For them, Kashmir may just be a tired old conundrum, for which they foolishly believe the BJP has found a lasting solution. Surely, however, as migrants themselves, their understanding of what is happening in Assam could be more nuanced. Or maybe it’s too much to ask of those who, in a world riven by refugee and migrant crises, are the most fortunate of migrants. Many of those in the Houston stadium, like people with an extra holiday home, probably hold US citizenship as well as Overseas Citizens of India certificates.

The “Howdy, Modi!” event marked the 22nd day since almost 2 million people in Assam found their names missing from the National Register of Citizens.

Like Kashmir, Assam is a border state with a history of multiple sovereignties, with centuries of migration, wars, invasion, continuously shifting borders, British colonialism, and more than 70 years of electoral democracy that has only deepened the fault lines in a dangerously combustible society.

That an exercise like the NRC even took place has to do with Assam’s very particular cultural history. Assam was among the territories ceded to the British by the Burmese after the First Anglo-Burmese War in 1826. At the time, it was a densely forested, scantily populated province, home to hundreds of communities—among them Bodos, Cachari, Mishing, Lalung, Ahomiya Hindus, and Ahomiya Muslims—each with its own language or speech practice, each with an organic, though often undocumented, relationship to the land. Like a microcosm of India, Assam has always been a collection of minorities jockeying to make alliances in order to manufacture a majority—ethnic as well as linguistic. Anything that altered or threatened the prevailing balance became a potential catalyst for violence.

The seeds for just such an alteration were sown in 1837, when the British, the new masters of Assam, made Bengali the official language of the province. It meant that almost all administrative and government jobs were taken by an educated, Hindu, Bengali-speaking elite. Although the policy was reversed in the early 1870s and Assamese was given official status along with Bengali, it shifted the balance of power in serious ways and marked the beginning of what has become an almost two-century-old antagonism between speakers of Assamese and Bengali.

Towards the middle of the 19th century, the British discovered that the climate and soil of the region were conducive to tea cultivation. Local people were unwilling to work as serfs in the tea gardens, so a large population of indigenous tribespeople were transported from central India. They were no different from the shiploads of indentured Indian laborers the British transported to their colonies all over the world. Today, the plantation workers in Assam make up 15 to 20 percent of the state’s population. Shamefully, these workers are looked down upon by local people and continue to live on the plantations, at the mercy of plantation owners and earning slave wages.

By the late 1890s, as the tea industry grew and as the plains of neighboring East Bengal reached the limits of their cultivation potential, the British encouraged Bengali Muslim peasants—masters of the art of farming on the rich, silty, riverine plains and shifting islands of the Brahmaputra, known as chars—to migrate to Assam. To the British, the forests and plains of Assam were, if not Terra nullius, then Terra almost-nullius. They hardly registered the presence of Assam’s many tribes, and freely allocated what were tribal commons to “productive” peasants whose produce would contribute to British revenue collection. The migrants came in the thousands, felled forests, and turned marshes into farmland. By 1930, migration had drastically changed both the economy and the demography of Assam.

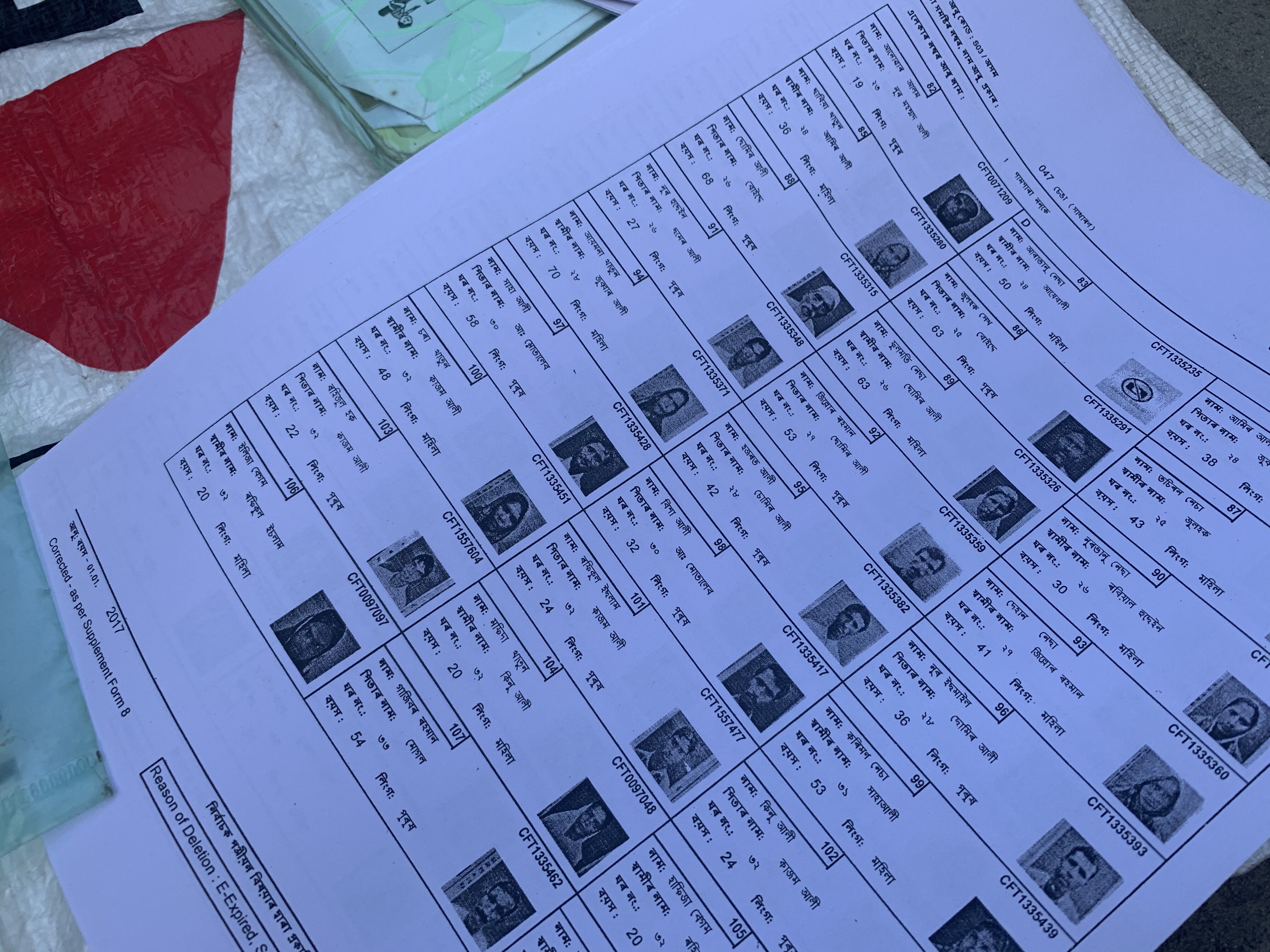

Detail of a printed electoral roll, one of the specified “link” documents required by the NRC. (Sanjay Kak)

At first, the migrants were welcomed by Assamese nationalist groups, but soon tensions arose—ethnic, religious and linguistic. They were temporarily mitigated when, in the 1941 census and then more emphatically in the 1951 census and then every census that followed, as a gesture of solidarity with their new homeland, the entire population of Bengali-speaking Muslims—whose local dialects are together known as the Miya language—designated Assamese as their mother tongue, thereby ensuring that it retained the status of an official language. Even today, Miya dialects are written in the Assamese script.

Over the years, the borders of Assam were redrawn continuously, almost dizzyingly. When the British partitioned Bengal in 1905, they attached the province of Assam to Muslim-majority East Bengal, with Dhaka as its capital. Suddenly, what was a migrant population in Assam was no longer migrant, but part of a majority. Six years later, when Bengal was reunified and Assam became a province of its own, its Bengali population became migrants once again. After the 1947 Partition, when East Bengal became a part of Pakistan, the Bengal-origin Muslim settlers in Assam chose to stay on. But Partition also led to a massive influx of Bengali refugees into Assam, Hindus as well as Muslims. This was followed in 1971 by yet another incursion of refugees fleeing from the Pakistan Army’s genocidal attack on East Pakistan and the liberation war that birthed the new nation of Bangladesh, which together took millions of lives.

So Assam was a part of East Bengal, and then it wasn’t. East Bengal became East Pakistan and East Pakistan became Bangladesh. Countries changed, flags changed, anthems changed. Cities grew, forests were felled, marshes were reclaimed, tribal commons swallowed by modern “development.” And the fissures between people grew old and hard and intractable.

The Indian government is so proud of the part it played in Bangladesh’s liberation from Pakistan. Indira Gandhi, the prime minister at the time, ignored the threats of China and the United States, who were Pakistan’s allies, and sent in the Indian Army to stop the genocide. That pride in having fought a “just war” did not translate into justice or real concern, or any kind of thought-out state policy for either the refugees or the people of Assam and its neighboring states.

The demand for a National Register of Citizens in Assam arose out of this unique, vexed, and complex history. Ironically, the word “national” here refers not so much to India as it does to the nation of Assam. The demand to update the first NRC, conducted in 1951, grew out of a student-led Assamese nationalist movement that peaked between 1979 and 1985, alongside a militant separatist movement in which tens of thousands lost their lives. The Assamese nationalists called for a boycott of elections unless “foreigners” were deleted from the electoral rolls—the clarion call was for “3D,” which stood for Detect, Delete, Deport. The number of so-called foreigners, based on pure speculation, was estimated to be in the millions. The movement quickly turned violent. Killings, arson, bomb blasts, and mass demonstrations generated an atmosphere of hostility and almost uncontrollable rage towards “outsiders.” By 1979, the state was up in flames. Though the movement was primarily directed against Bengalis and Bengali-speakers, Hindu communal forces within the movement also gave it an anti-Muslim character. In 1983, this culminated in the horrifying Nellie massacre, in which more than 2,000 Bengal-origin Muslim settlers were murdered over six hours.

In What the Fields Remember, a documentary about the massacre, an elderly Muslim who lost all his children to the violence tells of how one of his daughters, not long before the massacre, had been part of a march asking for “foreigners” to be expelled. Her dying words, he said, were, “Baba, are we also foreigners?”

In 1985, the student leaders of the Assam agitation signed the Assam Accord with the central government. That year, they won the state’s assembly elections and formed the state government. A date was agreed upon: Those who had arrived in Assam after midnight of 24 March 1971—the day the Pakistan Army began its attack on civilians in East Pakistan—would be expelled. The updating of the NRC was meant to sift the “genuine citizens” of Assam from post-1971 “infiltrators.”

Over the next several years, “infiltrators” detected by the border police, or those declared “Doubtful Voters”—D-Voters—by election officials, were tried under the Illegal Migrants Determination by Tribunal Act, passed in 1983 by a Congress Party government under Indira Gandhi. In order to protect minorities from harassment, the IMDT Act put the onus of disproving a person’s citizenship on the police or the accusing party—instead of burdening the accused with proving their citizenship. Since 1997, more than 400,000 D-voters and Declared Foreigners have been tried in Foreigners Tribunals. Over 1,000 are still locked up in detention centers, jails within jails where detainees don’t even have the rights that ordinary criminals do.

In 2005, the Supreme Court adjudicated a case that asked for the IMDT Act to be struck down on the grounds that it made the “detection and deportation of illegal immigrants nearly impossible.” In its judgment annulling the act, the court noted, “there can be no manner of doubt that the State of Assam is facing “external aggression and internal disturbance” on account of large scale illegal migration of Bangladeshi nationals.” Now, it put the onus of proving citizenship on the citizen. This completely changed the paradigm, and set the stage for the new, updated NRC. The case had been filed by Sarbananda Sonowal, a former president of the All Assam Students’ Union who is now with the BJP, and currently serves as the chief minister of Assam.

In 2013, the Supreme Court took up a case filed by an NGO called Assam Public Works that asked for illegal migrants’ names to be struck off electoral rolls. Eventually, the case was assigned to the court of Justice Ranjan Gogoi, who happens to be Assamese.

In December 2014, the Supreme Court ordered that an updated list for the NRC be produced within a year. Nobody had any clue about what could or would be done to the 5 million “infiltrators” that it was hoped would be detected. There was no question of them being deported to Bangladesh. Could that many people be locked up in detention camps? For how long? Would they be stripped of citizenship?

Millions of villagers living in far-flung areas were expected to produce a specified set of documents—“legacy papers”—that proved direct and unbroken paternal lineage dating back to 1971. The Supreme Court’s deadline turned the exercise into a nightmare. Impoverished, illiterate villagers were delivered into a labyrinth of bureaucracy, legalese, documentation, court hearings, and all the ruthless skulduggery that goes with them.

Mohila Biswas, foreground, wife of Ratan Biswas, who is currently in a detention centre in Goalpara, Assam. His mother and daughter-in-law are also in the frame. (Sanjay Kak)

The only way to reach the remote, seminomadic settlements on the shifting, silty “char” islands of the Brahmaputra is by often perilously overcrowded boats. The roughly 2,500 char islands are impermanent offerings, likely to be snatched back at any moment by the legendarily moody Brahmaputra and reoffered at some other location, in some other shape or form. The settlements on them are temporary, and the dwellings are just shacks. Yet some of the islands are so fertile, and the farmers on them so skilled, that they raise three crops a year. Their impermanence, however, has meant the absence of land deeds, of development, of schools and hospitals.

In the less fertile chars that I visited early last month, the poverty washes over you like the dark, silt-rich waters of the Brahmaputra. The only signs of modernity were the bright plastic bags containing documents that their owners—who quickly gather around visiting strangers—could not read but kept looking at anxiously, as though trying to decrypt the faded shapes on the faded pages and work out whether they would save them and their children from the massive new detention camp they had heard is being constructed deep in the forests of Goalpara. Imagine a whole population of millions of people like this, debilitated, rigid with fear and worry about their documentation. It’s not a military occupation, but it’s occupation by documentation. These documents are peoples’ most prized possessions, cared for more lovingly than any child or parent. They have survived floods and storms and every kind of emergency. Grizzled, sun-baked farmers, men and women, scholars of the land and the many moods of the river, use English words like “legacy document,” “link paper,” “certified copy,” “re-verification,” “reference case,” “D-voter,” “declared foreigner,” “voter list,” “refugee certificate”—as though they were words in their own language. They are. The NRC has spawned a vocabulary of its own. The saddest phrase in it is “genuine citizen.”

In village after village, people told stories about being served notices late at night that ordered them to appear in a court two or three hundred kilometers away by the next morning. They described the scramble to assemble family members and their documents, the treacherous rides in small rowboats across the rushing river in pitch darkness, the negotiations with canny transporters on the shore who had smelled their desperation and tripled their rates, the reckless drive through the night on dangerous highways. The most chilling story I heard was about a family traveling in a pickup truck that collided with a roadworks truck carrying barrels of tar. The barrels overturned, and the injured family was covered in tar. “When I went to visit them in hospital,” the young activist I was traveling with said, “their young son was trying to pick off the tar on his skin and the tiny stones embedded in it. He looked at his mother and asked, ‘Will we ever get rid of the kala daag [stigma] of being foreigners?’”

<strong>Islands in the stream:</strong> Temporary homes on Char Marichakandi, an island of silt in the Brahmaputra River. (Sanjay Kak)

And yet, despite all this, despite reservations about the process and its implementation, the updating of the NRC was welcomed (enthusiastically by some, warily by others) by almost everybody in Assam, each for reasons of their own. Assamese nationalists hoped that millions of Bengali infiltrators, Hindu as well as Muslim, would finally be detected and formally declared “foreigners.” Indigenous tribal communities hoped for some recompense for the historical wrong they had suffered. Hindus as well as Muslims of Bengal origin wanted to see their names on the NRC to prove they were “genuine” Indians, so that the kala daag of being “foreign” could be laid to rest once and for all. And the Hindu nationalists—now in government in Assam, too—wanted to see millions of Muslim names deleted from the NRC. Everybody hoped for some form of closure.

After a series of postponements, the final updated list was published on August 31, 2019. The names of 1.9 million people were missing. That number could yet expand because of a provision that permits people—neighbors, enemies, strangers—to lodge appeals. At last count, more than 200,000 objections to the draft NRC had been raised. A great number of those who have found their names missing from the list are women and children, most of whom belong to communities where women are married in their early teenage years, and by custom have their names changed. They have no “link documents” to prove their legacy. A great number are illiterate people whose names or parents’ names have been wrongly transcribed over the years: a H-a-s-a-n who became a H-a-s-s-a-n, a Joynul who became Zainul, a Mohammad whose name has been spelled in several ways. A single slip, and you’re out. If your father died, or was estranged from your mother, if he didn’t vote, wasn’t educated, and didn’t have land, you’re out. Because in practice, mothers’ legacies don’t count. Among all the prejudices at play in updating the NRC, perhaps the greatest of all is the built-in, structural prejudice against women and against the poor. And the poor in India today are made up mostly of Muslims, Dalits, and Tribals.

All the 1.9 million people whose names are missing will now have to appeal to a Foreigners Tribunal. There are, at the moment, 100 Foreigners Tribunals in Assam, and another 1,000 are in the pipeline. The men and women who preside over them, known as “members” of the tribunals, hold the fates of millions in their hands, but have no experience as judges. They are bureaucrats or junior lawyers, hired by the government and paid generous salaries. Once again, prejudice is built into the system. Government documents accessed by activists show that the sole criterion for rehiring members whose contracts have expired is the number of appeals they have rejected. All those who have to go in appeal to the Foreigners Tribunals will also have to hire lawyers, perhaps take loans to pay their fees or sell their land or their homes, and surrender to a life of debt and penury. Many of course have no land or home to sell. Several have committed suicide.

After the whole elaborate exercise and the millions of rupees spent on it, all the stakeholders in the NRC are bitterly disappointed with the list. Bengal-origin migrants are disappointed because they know that rightful citizens have been arbitrarily left out. Assamese nationalists are disappointed because the list has fallen well short of excluding the 5 million purported infiltrators” they expected it to detect, and because they feel too many illegal foreigners have made it onto the list. And India’s ruling Hindu nationalists are disappointed because it is estimated that more than half of the 1.9 million are non-Muslims. (The reason for this is ironic. Bengali Muslim migrants, having faced hostility for so long, have spent years gathering their “legacy papers.” Hindus, being less insecure, have not.)

Justice Gogoi ordered the transfer of Prateek Hajela, the chief coordinator of the NRC, giving him seven days to leave Assam. Justice Gogoi did not offer a reason for this order.

Demands for a fresh NRC have already begun.

How can one even try to understand this craziness, except by turning to poetry? A group of young Muslim poets, known as the Miya poets, began writing of their pain and humiliation in the language that felt most intimate to them, in the language that until then they had only used in their homes—the Miya dialects of Dhakaiya, Maimansingia, and Pabnaiya. One of them, Rehna Sultana, in a poem called “Mother,” wrote:

Ma, ami tumar kachchey aamar porisoi diti diti biakul oya dzai

Mother, I’m so tired, tired of introducing myself to you

When these poems were posted and circulated widely on Facebook, a private language suddenly became public. And the old specter of linguistic politics reared its head again. Police cases were filed against several Miya poets, accusing them of defaming Assamese society. Rehna Sultana had to go into hiding.

That there is a problem in Assam cannot be denied. But how is it to be solved? The trouble is that once the torch of ethno-nationalism has been lit, it is impossible to know in which direction the wind will take the fire. In the new union territory of Ladakh—granted this status by the abrogation of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status—tensions simmer between Buddhists and Shia Muslims. In the states of India’s northeast, sparks have already begun to ignite old antagonisms. In Arunachal Pradesh, it is the Assamese who are unwanted immigrants. Meghalaya has closed its borders with Assam, and now requires all “outsiders” staying more than 24 hours to register with the government under the new Meghalaya Residents Safety and Security Act. In Nagaland, 22-year-long peace talks between the central government and Naga rebels have stalled over demands for a separate Naga flag and constitution. In Manipur, dissidents worried about a possible settlement between the Nagas and the central government have announced a government-in-exile in London. Indigenous tribes in Tripura are demanding their own NRC in order to expel the Hindu Bengali population that has turned them into a tiny minority in their own homeland.

Far from being deterred by the chaos and distress created by Assam’s NRC, the Modi government is making arrangements to import it to the rest of India. To take care of the possibility of Hindus and its other supporters being caught up in the NRC’s complexities, as has happened in Assam, it has drafted a new Citizenship Amendment Bill. (After being passed in Parliament, it is now the Citizenship Amendment Act.) It says that all non-Muslim “persecuted minorities” from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan—meaning Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, and Christians—will be given asylum in India. By default, the CAB will ensure that those deprived of citizenship will only be Muslims.

Before the process begins, the plan is to update the National Population Register. This will involve a door-to-door survey in which, in addition to basic census data, the government plans to add to its collection of iris scans and other biometric data. It will be the mother of all data banks.

Shabjan Nessa, 77, from Marichakandi Char. Incapacitated by a leg injury on her way to an appearance at the NRC office. Her name is missing from the final list; she will now be required to appear at a Foreigners Tribunal. (Sanjay Kak)

The groundwork has already begun. In one of his first acts as home minister, Amit Shah issued a notification permitting state governments across India to set up Foreigners Tribunals and detention centers manned by non-judicial officers with draconian powers. The governments of Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh, and Haryana have already begun work. As we have seen, the NRC in Assam grew out of a very particular history. To apply it to the rest of India is pure malevolence. The demand for an updated NRC in Assam is more than 40 years old. There, people have been collecting and holding on to their documents for 50 years. How many people in India can produce “legacy documents”? Perhaps not even our prime minister—whose date of birth, college degree, and marital status have all been the subject of national controversies.

We are being told that the India-wide NRC is an exercise to detect several million Bangladeshi “infiltrators”—“termites,” as our home minister likes to call them. What does he imagine language like this will do to India’s relationship with Bangladesh? Once again, phantom figures that run into the tens of millions are being thrown around. There is no doubt that there are a great many undocumented workers from Bangladesh in India. There is also no doubt that they make up one of the poorest, most marginalized populations in the country. Anybody who claims to believe in the free market should know that they are only filling a vacant economic slot by doing work that others will not do, for wages that nobody else will accept. They do an honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay. They are not the corporate con men destroying the country, stealing public money or bankrupting the banks. They’re only a decoy, a Trojan horse for the RSS’s real objective, its historic mission.

The real purpose of an all-India NRC, coupled with the CAB, is to threaten, destabilize, and stigmatize the Indian Muslim community, particularly the poorest among them. It is meant to formalize an unequal, tiered society, in which one set of people has no rights and lives at the mercy, or on the good will, of another—a modern caste system, which will exist alongside the ancient one, in which Muslims are the new Dalits. Not notionally, but actually. Legally. In places like West Bengal, where the BJP is on an aggressive takeover drive, suicides have already begun.

Here is M.S. Golwalkar, the supreme leader of the RSS in 1940, writing in his book We, or Our Nationhood Defined:

Ever since that evil day, when Moslems first landed in Hindustan, right up to the present moment, the Hindu Nation has been gallantly fighting to take on these despoilers. The Race Spirit has been awakening.In Hindustan, land of the Hindus, lives and should live the Hindu Nation.…

All others are traitors and enemies to the National Cause, or, to take a charitable view, idiots.… The foreign races in Hindustan…may stay in the country, wholly subordinated to the Hindu Nation, claiming nothing, deserving no privileges, far less any preferential treatment—not even citizens’ rights.

He continues:

To keep up the purity of its race and culture, Germany shocked the world by her purging the country of the Semitic races—the Jews. Race pride at its highest has been manifested here, a good lesson for us in Hindustan to learn and profit by.

How do you translate this in modern terms? Coupled with the Citizenship Amendment Bill, the National Register of Citizenship is India’s version of Germany’s 1935 Nuremberg Laws, by which German citizenship was restricted to only those who had been granted citizenship papers—legacy papers—by the government of the Third Reich. The amendment against Muslims is the first such amendment. Others will no doubt follow, against Christians, Dalits, Communists—all enemies of the RSS.

The Foreigners Tribunals and detention centers that have already started springing up across India may not, at the moment, be intended to accommodate hundreds of millions of Muslims. But they are meant to remind us that only Hindus are considered India’s real aboriginals, and don’t need those papers. Even the 460-year-old Babri Masjid didn’t have the right legacy papers. What chance would a poor farmer or a street vendor have?

This is the wickedness that the 50,000 people in the Houston stadium were cheering. This is what the president of the United States linked hands with Modi to support. It’s what the Israelis want to partner with, the Germans want to trade with, the French want to sell fighter jets to, and the Saudis want to fund.

Perhaps the whole process of the all-India NRC can be privatized, including the data bank with our iris scans. The employment opportunities and accompanying profits might revive our dying economy. The detention centers could be built by the Indian equivalents of Siemens, Bayer and IG Farben. It isn’t hard to guess what corporations those will be. Even if we don’t get to the Zyklon B stage, there’s plenty of money to be made.

We can only hope that someday soon, the streets in India will throng with people who realize that unless they make their move, the end is close.

If that doesn’t happen, consider these words to be intimations of an ending from one who lived through these times.

This post has been updated.

Arundhati RoyArundhati Roy studied architecture in New Delhi, where she now lives. She is the author of the novels The God of Small Things, for which she received the 1997 Booker Prize, and The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. A collection of her essays from the past 20 years, My Seditious Heart, was recently published by Haymarket Books.

Đăng nhận xét