It’s called “ecocide” and even the pope is talking about it.

More than a decade ago, British lawyer Polly Higgins quit her high-flying job and sold her house. She wanted the time and money to throw herself into campaigning for a law she, and many others, believed could change the world and give us a vital tool to tackle climate change.

Higgins was fighting for “ecocide” to be recognized as an international crime against peace. Defined as the mass damage or destruction of natural living systems, the crime would impose a duty of care on individuals not to destroy the environment and would hold government ministers and corporate CEOs criminally responsible for the environmental damage they caused.

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

The aim: to close a gap in the law, which allows the perpetrators of large-scale environmental crimes to avoid accountability. The method: to add ecocide to the list of crimes prosecuted by the International Criminal Court (the ICC) in The Hague.

Currently, the ICC is tasked with prosecuting individuals accused of committing four “crimes against peace”: war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide and crimes of aggression. Ecocide would be the fifth.

Earlier this year Higgins died from cancer at the age of 50, but not before she got to see a new generation of activists pick up her torch, with the climate protest group Extinction Rebellion demanding that ecocide be recognized as a crime.

Her global crusade, Stop Ecocide: Change the Law, continues to fight on under the leadership of its co-founder, Jojo Mehta. And now, one of Higgins’ final efforts is starting to become a reality.

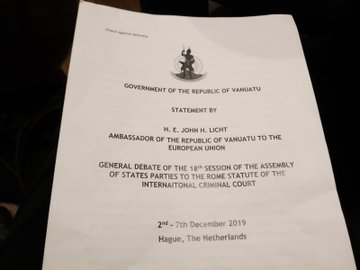

Before her death, she had been working with the South Pacific Island of Vanuatu ― which is incredibly vulnerable to climate change. This week, at the ICC’s annual meeting, Ambassador John Licht of Vanuatu called on the court to consider formalizing the crime of ecocide: “We believe this radical idea merits serious discussion.” It marks the first time since 1972 that a state representative has called for a law of ecocide in an international forum.

“This is an idea whose time has not only come, it’s long overdue. It’s committed and courageous of Vanuatu,” says Mehta.

“Current law is so deeply anthropocentric,” she explains. “It’s the Earth itself that needs a really good lawyer.” Mehta believes ecocide should work as a deterrent. “In an ideal world, we would see as few people in the dock as possible because the crime is no longer happening,” says Mehta. Big companies often have budgets set aside for civil litigation against them to cover any fines, so “it doesn’t stop them from engaging in destructive activities,” says Mehta. But criminal liability brings with it the possibility of prison time.

The role of Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, in the developing crisis in the Amazon is a good example of why we need criminal accountability for environmental destruction, argues Mehta. He is the “poster boy for the need for the crime of ecocide,” she says.

Bolsonaro came to power on pledges to open up the Amazon to business. Under his leadership, the rainforest lost 3,769 square miles of forest cover ― an area roughly twice the size of Grand Canyon National Park ― between August 2018 and July 2019.

This summer, more than 70,000 fires ripped through the rainforest, many deliberately ignited to clear huge areas for agriculture and livestock operations. The smoke traveled thousands of miles, blackening the skies of São Paulo for days. Around the world, millions tweeted out #PrayForAmazonia while the Amazon moved closer to what scientists fear will be an irreversible ecological tipping point, where dry savanna will permanently replace what was once lush, tropical forest.

Since taking office, Bolsonaro’s permissive rhetoric has emboldened companies and workers to destroy vast tracts of forests in their quest for wealth, while at the same time he has stripped funds from the country’s environment agency.

“The current government has implicitly, and explicitly, given a green light to farmers and others to clear forests, including in areas where that would be illegal,” says Nigel Sizer, chief program officer for the Rainforest Alliance. “That’s a threat to the largest expanse of tropical rainforest on Earth, which is vital for our weather patterns, hosts the largest number of species of plants, and is key for climate stability.”

Bolsonaro, who has also focused on policies to weaken Indigenous rights and has a long history of making racist remarks against indigenous people, may already find himself before the ICC. In late November, a collection of Brazilian lawyers and human rights advocates requested that the court investigate the president for “incitement to genocide and widespread systematic attacks against indigenous peoples.”

But by focusing on humans alone, campaigners like Mehta think the Rome Statute (the founding document of the ICC) ignores the rights of, and humanity’s stake in, nature. Currently, criminal charges in the international court need to show clear victims: human victims. Under this logic, even if the entire Amazon rainforest was destroyed under Bolsonaro’s watch, if no people were harmed, he can’t be held accountable.

Campaigners, lawyers and activists have been arguing since the 1970s for ecocide to be recognized as a crime. While it was under consideration during the formation of the ICC, it was never adopted. Higgins’ arrival on the scene a decade ago ― with her campaigning zeal and ability to capture public attention ― gave fresh momentum to the battle.

As Higgins always maintained, the process to get ecocide recognized is fairly straightforward. At least one of the court’s member states must propose an ecocide amendment to the Rome Statute. Once proposed, it would require a two-thirds majority vote of the 122 member states of the ICC. Individual member states would then need to ratify and enforce the law.

Even if the big players like the U.S. or Brazil declined to ratify, they would still be liable for ecocidal practices in nations that had done so, and those accused of ecocide would face potential arrest if they set foot in a country that had ratified.

The ICC adopting ecocide as a new crime would send a “strong signal that we are inching towards less tolerance for large-scale crimes,” says Alessandra Lehmen, a Brazilian environmental lawyer and law scholar.

There are already signs the ICC is prepared to put more focus on environmental crimes. In 2016 the court released a policy paper stating that the prosecutor will give “particular consideration” to prosecuting crimes that are committed “by means of … the destruction of the environment, the illegal exploitation of natural resources or the illegal dispossession of land.” This paper effectively enables the court to try environmental crimes, but not where there is an absence of human victims.

Galvanized by this expanded scope, lawyers are hopeful cases that fit the bill will now be prioritized by the ICC. A case involving land-grabbing in Cambodia, for example, where hundreds of thousands of people say they were pushed off their land to make way for companies to develop it, is under consideration for investigation.

Richard Rogers, a U.K.-based international criminal lawyer, brought the case to the ICC in 2014. “Cambodia is one of the most shocking examples of this global land rush where the ruling elite are trying to grab as many resources as quickly as possible,” he said. Rogers hopes an increased focus on environmental destruction will help prosecute peacetime crimes like land grabs that cause mass displacement.

National courts can already hold companies and states financially accountable for environmental harm using civil litigation. But adding a criminal component to environmental destruction would make the stakes vastly higher. Not only would individuals have to weigh whether their actions might get them locked up in The Hague, it also would have huge implications for the funding of their businesses.

“Banks cannot finance something they know or suspect to be criminal,” explains Mehta. “When Polly [once] asked the head of a bank why they continued to finance ecocidal practices, the answer was, ‘It’s not a crime.’”

Mehta hopes that by equating environmental damage with other crimes, it will create a new baseline. “You can’t go around killing people. And now you can’t go around destroying ecosystems,” she says.

The ecocide campaign has its detractors, however. One of the main criticisms is of the reach and effectiveness of the ICC. Since its establishment in 2002, the court has only ever pursued 27 cases of crimes against peace; only six defendants have ultimately been convicted. All of these criminal cases relate to activities that took place in Africa, leading to concerns that the court disproportionately focuses on developing countries. However, the ICC has opened investigations into cases in Georgia and, most recently this month, Bangladesh and Myanmar.

“The people who tend to be held accountable for crimes against humanity are the leaders of smaller, weaker countries,” says the Rainforest Alliance’s Sizer. “We do not see the leaders of European countries or the United States being arrested and shipped off to The Hague. These people are too powerful. There’s a real question as to whether the head of state of a country like Brazil could ever be held accountable in this way for ecological crimes.”

Other nongovernmental organizations that work closely with Indigenous people in the Amazon worry that environmental destruction could become divorced from its impact on the tribes that steward the land.

“When we’re talking about the invasion of the Amazon forest, the human lives threatened and the ecosystems destroyed go together. There is no destruction of the Amazon that happens without human violence,” says João Coimbra Sousa, Amazon Watch’s legal consultant based in Brazil.

But for Mehta and Rogers, the benefit of ecocide law lies in its preventive power ― making powerful people think twice before taking environmentally destructive actions.

“The ICC is not effective if you’re just looking at prosecutions,” says Rogers. “But it is effective if you’re looking at stigma. I think the preventative effect is quite significant. It’s the reputation damage. It’s a great opportunity for the ICC to prosecute cases, like Cambodia, or other cases involving ecocide where the potential perpetrator has a lot to lose.”

The dialogue around climate change and moral responsibility greatly expanded in 2019, thanks in large part to the “Greta Effect” ― the awareness raised by 16-year-old Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg. Climate change strikes and protests have scaled up across the world. And in November, Pope Francis announced plans to include a definition of ecological sins in the Roman Catholic Church’s official teaching. Even French President Emmanuel Macron publicly referred to the damage to the Amazon as “ecocide.”

And as more evidence has emerged that major fossil fuel companies knew about climate change but spent the last decades lobbying against policies to tackle it, climate litigation has also grown in popularity. There are currently active lawsuits against governments and fossil fuel companies for their alleged complicity in the climate crisis in 28 countries.

During a 2011 mock trial at the U.K. supreme court, two CEOs were found guilty on two indictments of ecocide of Canada’s Athabasca tar sands ― a case without direct human victims. So it’s not just government officials that could be held accountable. CEOs of big fossil fuel companies could potentially be caught by the new crime.

Other heinous acts weren’t considered morally reprehensible by the public until they were criminalized, Mehta says. When the government officially condemns something like environmental destruction, “you’ve got something for civil society to point at, at a moral level.”

With support building and Vanuatu’s call to action, Mehta says she’s optimistic about an ecocide amendment being formally introduced to the ICC at the next annual assembly in December 2020. “The whole discourse around climate and ecological emergency has changed completely,” she says. “The civil mobilization we’re seeing around the world means that people hear what we’re saying.”

The challenge ahead, says Rogers, is defining ecocide in such a way that lawyers are able to show direct consequence on the ground and also to work out how to get around the need for “intent.” While the other crimes against peace require an intent to harm, the motives of perpetrators of ecocide is more likely to be profit or political gain rather than an explicit intent to cause environmental damage.

Getting other nations on board may be less of a challenge, particularly the small island states which, like Vanuatu, stand to be greatly affected by climate change, says Rogers. “For the first time in history, we are within the political context where states may add a fifth core statute,” he adds.

Mehta, too, says she is optimistic. “If you’d asked me last year, my answer might be different,” she notes. “The whole discourse around climate and ecological emergency has changed completely. We had a very small team with Polly Higgins and people were concerned that the work wouldn’t continue without her. But the reverse has happened.”

If it matters to you, it matters to us. Support HuffPost’s journalism here. For more content and to be part of the “This New World” community, follow our Facebook page.

HuffPost’s “This New World” series is funded by Partners for a New Economy and the Kendeda Fund. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundations. If you have an idea or tip for the editorial series, send an email to thisnewworld@huffpost.com.

Đăng nhận xét