These ancient, sacred groves can help shape conservation policy amid rapid urbanisation and rural change, writes Chris Coggins

To

look at China’s rural landscapes today is to see the cumulative effects

of long term, intensive human activity and profound ecological

transformation. This is especially the case in agricultural regions,

which were once covered by tropical, subtropical, and temperate forests.

In pre-industrial times, however, anthropogenic environmental change was not the zero-sum game it is now. Chinese peasants were neither mystical stewards of ecological harmony nor ruthless exterminators of diverse fauna and flora. Predominantly self-reliant communities crafted intricate landscapes in which humans relied on many wild and domesticated species of plants and animals for their livelihood. The fruits of their labours deserve our utmost attention, and fengshui forests are a prime example.

In pre-industrial times, however, anthropogenic environmental change was not the zero-sum game it is now. Chinese peasants were neither mystical stewards of ecological harmony nor ruthless exterminators of diverse fauna and flora. Predominantly self-reliant communities crafted intricate landscapes in which humans relied on many wild and domesticated species of plants and animals for their livelihood. The fruits of their labours deserve our utmost attention, and fengshui forests are a prime example.

Sign up to our newsletter

Want more stories like this in your inbox? Subscribe to chinadialogue's weekly newsletter to get our latest articles.

I might not have seen the fengshui forests had they not been pointed out to me. The surrounding slopes bore a mélange of broadleaf evergreen trees, cultivated stands of giant bamboo, conifer plantations and small patches of young, successional forest. He Lian, a biogeographer from the Fujian Provincial Museum, gestured toward a patch of large, luxuriant trees on a small mountain above a temple, saying in Mandarin: “That’s a fengshui forest.”

Forest protection

I was in Meihuashan to conduct research on community resource management and state-led tiger conservation efforts. Fengshui forests were the first evidence I found that local people had helped protect patches of the subtropical broadleaf forests that once covered Fujian and neighbouring southern provinces. Over the course of centuries, village communities protected species-rich woodlands and planted new groves, even as they busily built rice paddies across wetlands and up terraced slopes; burned mountain uplands; and propagated vast stands of maozhu bamboo and plantations of pines and Chinese cedars.

Many of these communally-protected, sacred forests have survived to the present, and they are strictly protected because villagers believe that they improve local fengshui.

“Fengshui” means “wind-water”. It denotes an ancient system for determining the most auspicious locations and designs for towns, villages, houses, tombs and other components of the built environment based on the flow and quality of life-generating and sustaining energies known as “qi”.

This ancestral hall in Gutian township, Shanghang county, Fujian, is backed by a large fengshui forest. This is the famous site of the 1929 Gutian Congress in which Mao Zedong and Zhu De convened the ninth meeting of the Chinese Communist Party (Image: Chris Coggins)

The establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 spelled the abolition of fengshui due to its apparent lack of scientific validity and its association with “feudal superstition” These were seen as obstacles to socialist modernisation. The ban lasted 30 years until the Opening and Reform Period, and its severity accounts for why so few people in urban China know the term “fengshuilin”.

Fortunately, rural people continue to protect the forests, and a growing number of botanists, foresters, conservationists, and government officials are becoming aware of them as well.

This awareness is essential for their protection as rural China undergoes one of the most dramatic transformations in the country’s history: large scale, government-orchestrated urbanisation.

My research in western Fujian in the 1990s raised questions about the state of fengshuilin in other parts of China, and since 2011 I have researched their geographic distribution, conservation status, ecological significance and cultural history throughout their range in southern and central China.

This multidisciplinary project requires small teams of Chinese and non-Chinese specialists, including local people, tree identification experts, tree ring analysts and aquatic ecologists. We have completed field surveys in 57 villages in 17 counties spanning the five provinces of Fujian, Jiangxi, Guangdong, Hunan, and Anhui.

We are midway through the project and we have yet to determine the full geographic extent of fengshuilin, but we hypothesise that they can still be found in most counties across southern and central China from just north of the Yangtze Basin to the southern coasts and the island of Hainan.

The flow of qi

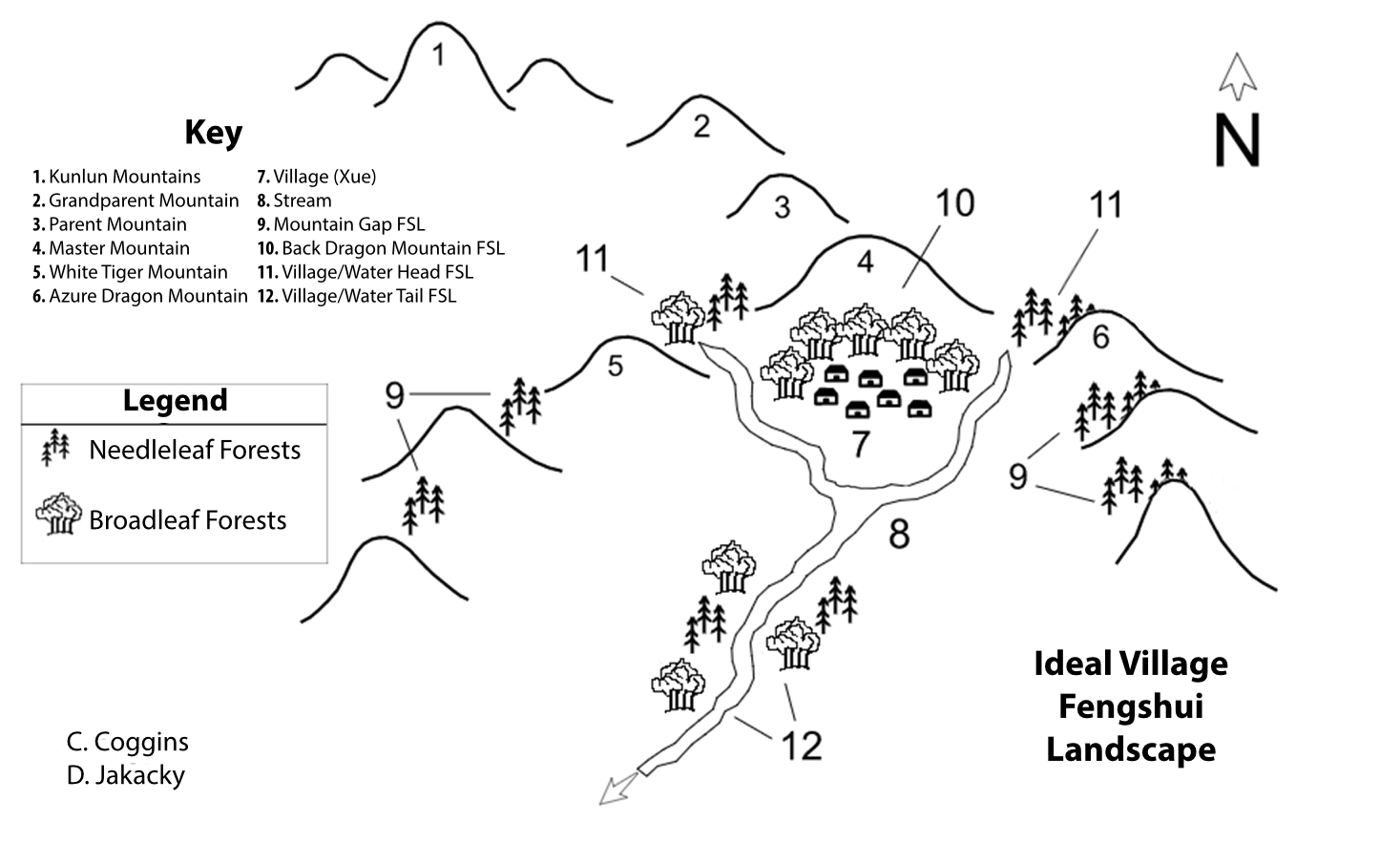

Fengshui forests are common pool resources and indispensable parts of the village landscape, meaning that villagers manage them collectively for mutual benefit. Ideal settlement sites are those that attract the most auspicious celestial and terrestrial forces, embodied in advantageous flows of qi.

Qi is said to be carried by wind and water (thus the term fengshui) and to flow through underground “dragon veins” that follow ridgelines and spurs. Villages are best sited at a point called the xue, the “lair”, “cave”, or “hole”, where forces of yin (feminine, dark, soft, negative polarity) and yang (masculine, light, hard, positive polarity) find balance. The xue is ideally above the floodplain and surrounded by mountains to the north, west, and east. This forms a u-shape barrier against cold northerly winter winds, yet is open to incoming solar radiation from the south that warms the village in winter and enhances crop growth in warmer months.

Fengshui forests are meant to improve qi flow. In microclimatic and hydrological terms this means regulating flows of wind and water in the residential and agricultural areas of the settlement.

In a summer 2017 interview, Wang Lishen, a fengshui master in Taqian village, Yifeng county, Jiangxi connected the spiritual and ecological dimensions of fengshui and fengshuilin in plain terms that, nevertheless, connote a complex human-nature reciprocity in which forests protect humans, depend on human protection and embody a quintessentially human essence:

“Fengshuilin

were handed down by our ancestors…There’s a mountain behind this house

and water in front. Green mountains and clear rivers – that’s [good]

fengshui… Without wind or water there’s no fengshui… Fengshui and

fengshuilin are closely related – in terms of the natural world, the

forests block wind and improve the soil. When storms and other natural

disasters hit, forests stand strong. From another perspective, the

mountain is behind and the human is in front of it; the fengshui forest

acts as a person, it is a human, thus the place has human essence/qi

(renqi)… If your place lacks good fengshui the forest cannot be so good

and luxuriant. Forests grow better in places where people have settled

in.”

Before

1949, fengshuilin were protected by a system of punishments imbedded

within traditional “village law and customary pacts” (cunguiminyue).

Violations were rare but with severe punishments. These included

sacrificing a pig – a devastating penalty; withholding food;

incineration of harvested timber; public beating; and drowning in a cage

submerged in a nearby stream.Such dramatic punishments no longer exist. Today forestry officials in Jiangxi and Fujian are beginning to view fengshui forests as unique cultural and ecological resources representing Chinese people’s distinctive socio-ecological heritage.

Given the upward trajectory of China’s nature conservation system, which included 446 national-level nature reserves in 2016 and 2,740 nature reserves at all administrative levels in 2015, fengshui forests hold great potential to contribute to conservation planning and serve as community-based protected areas in their own right.

Some fengshuilin are designated “small protected areas” (baohu xiaoqu), and these exist both within and outside of larger nature reserves. This strategy emerged in northeast Jiangxi’s Wuyuan county and is used in Fujian as well.

Emerging threats

But the future of China’s rural communities is less certain. In 36 villages where we discussed outmigration, an average of 60% of adults 40 years of age and under have moved to cities for work. Most will never return to their home villages except to visit, as residence permit policies encourage migration to nearby cities and towns (chengzhenhua).

By 2020, several hundred million farmers will resettle in township and county seats. Within a generation many villages may be abandoned, replaced by agribusiness, industry, tourism, residential gentrification, or other development schemes. Without community forest commons, what value will be ascribed to fengshuilin? Will they be cleared to make way for more lucrative landscapes? In Hong Kong, many former village fengshuilin became “country parks”, places of recreation, nature conservation, and environmental education.

Effective fengshuilin conservation requires accurate and detailed knowledge of their role in the long history of southern China’s rural communities. We hope to increase international understanding of these forests and the spiritual and socio-ecological practices they exemplify – traditions and innovations that deserve cross-cultural analysis in the context of both China’s ecological challenges and recent advances in social theories on humans, nature, and ecological citizenship in a time of global environmental crisis.

State oversight is crucial, even in areas where communities remain intact. State-local governance can enhance large scale habitat restoration and connectivity, providing a refuge for biodiversity, unique socio-ecological features, and maintaining nodes and corridors in large protected areas.

Greater recognition and protection of fengshuilin enhances the potential for long term, community-based, conservation rooted in a spiritual sense of place, a critical goal for nations worldwide. Fengshuilin hold much valuable information about the past, present, and potential future relationships between humans and nature. They embody adaptive philosophical and technical engagements within a world full of changing values.

Đăng nhận xét