January 15, 2022

Weighing 80-100kg and sporting long straight horns, white spots on its face and large facial scent glands, the saola does not sound like an animal that would be hard to spot.

But it was not until 1992 that this elusive creature was discovered, becoming the first large mammal new to science in more than 50 years.

Nicknamed the “Asian unicorn”, the saola continues to be elusive. They have never been seen by a biologist in the wild and have been camera-trapped only a handful of times. There are reports of villagers trying to keep them in captivity but they have died after a few weeks, probably due to the wrong diet.

It was during a survey of wildlife in the remote Vũ Quang nature reserve, a 212 square mile forested area of north central Vietnam, in 1992, that biologist Do Tuoc came across two skulls and a pair of trophy horns belonging to an unknown animal.

Twenty more specimens, including a complete skin, were subsequently collected and, in 1993, laboratory tests revealed the animal to be not only a new species, but an entirely new genus in the bovid family, which includes cattle, sheep, goats and antelopes.

Initially named Vu Quang Ox, the animal was later called saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) – meaning “spindle horns”, the arms or posts (sao) of a spinning wheel (la) according to Lao-speaking ethnic groups in Laos and neighbouring Vietnam.

The discovery was hailed as one of the most spectacular zoological discoveries of the 20th century but less than 30 years later the saola population is believed to have declined massively due to commercial wildlife poaching, which has exploded in Vietnam since 1994.

Even though the saola is not directly targeted by poachers, intensive commercial snaring that supplies animals for use in traditional Asian medicine or as bushmeat serves as the primary threat.

Despite efforts to improve patrolling of nature reserves in the Annamite mountains, a major mountain range extending about 680 miles through Laos, Vietnam and into north-east Cambodia, poaching has been intensifying. “Thousands of people use snares, so there are millions of them in the forest, which means populations of large mammals and some birds have no way to escape and are collapsing throughout the Annamites,” says Minh Nguyen, a PhD student at Colorado State University, who studies the impact of snares on critically endangered large-antlered muntjac.

In 2001, the saola population was estimated to number 70 to 700 in Laos and several hundred in Vietnam. More recently, experts have put the number at fewer than 100 – a decline that led to the species being listed as critically endangered on the IUCN red list in 2006, the highest risk category that a species can have before extinction in the wild. The animal was last camera-trapped in 2013 in the Saola Nature Reserve in central Vietnam. Since then, villagers continue to report its presence in areas in and around Pu Mat national park in Vietnam and in Bolikhamxay province in Laos.

We stand at a moment of conservation history. We know how to find and save this magnificent animal. We just need the world to come together

William Robichaud, Saola Foundation

In 2006, William Robichaud and Simon Hedges, a biologist and specialist on wildlife conservation and countering the illegal wildlife trade in Asia and Africa, co-founded the Saola Working Group (SWG) with the aim of finding the last saolas in the wild for a captive breeding programme, in order to reintroduce the species back into the wild in future, in a natural habitat that is free from threats.

The SWG connects conservation organisations in Laos and Vietnam to raise awareness, collect information from local people, and search for saola. But the animals continue to elude the team. Between 2017 and 2019, the SWG carried out an intensive search using 300 camera traps in an 11 square mile area of the Khoun Xe Nongma national protected area in Laos. Not one of the million photographs captured saola.

According to the IUCN, only about 30% of potential Saola habitat has had any form of wildlife survey and potentially as little as 2% has been searched intensively for the species. Technologies limit the capabilities – camera traps are not good at detecting individual animals that are spread across a large area, especially in the damp, dense forest of the saola range. In August this year, the IUCN Species Survival Commission called for more investment in the search for the saola. “It is clear that search efforts must be significantly ramped up in scale and intensity if we are to save this species from extinction,” said Nerissa Chao, Director of the IUCN SSC Asian Species Action Partnership

One organisation, the Saola Foundation, is raising money for a new initiative that would train dogs to detect saola signs such as dung. Any samples would then be studied onsite using rapid saola-specific DNA field test kits being developed in conjunction with the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Molecular Laboratory in New York. Should the kits return a positive result within an hour, expert wildlife trackers will start searching for saola in the forest.

If successful, captured saolas will be taken to a captive breeding centre being developed by the SWG and the Vietnamese government at Bạch Mã national park in central Vietnam.

“We stand at a moment of conservation history,” says Robichaud, who is president of the Saola Foundation. “We know how to find and save this magnificent animal, which has been on planet Earth for perhaps 8m years. We just need the world to come together and support the effort. It won’t cost much, and the reward, for saola, for the Annamite mountains, and for ourselves, will be huge.”

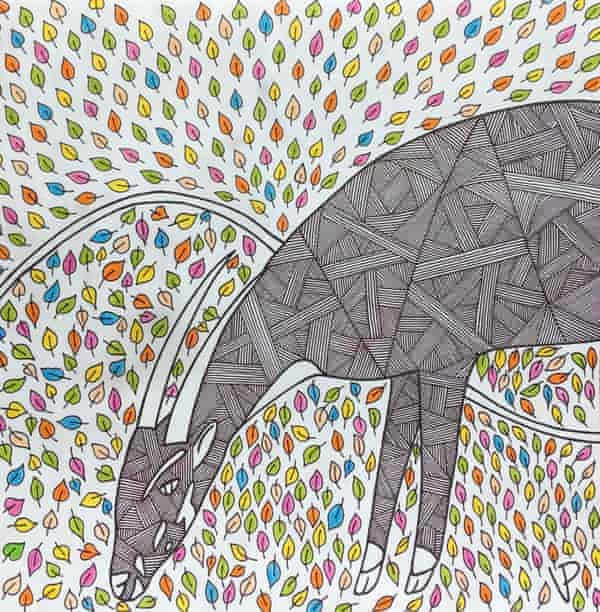

This article by Veronika Perková was first published by The Guardian on 7 January 2022. Lead Image: The saola has only been captured on camera a handful of times. Photograph: WWF/AP.

What you can do

Support ‘Fighting for Wildlife’ by donating as little as $1 – It only takes a minute. Thank you.

Fighting for Wildlife supports approved wildlife conservation organizations, which spend at least 80 percent of the money they raise on actual fieldwork, rather than administration and fundraising. When making a donation you can designate for which type of initiative it should be used – wildlife, oceans, forests or climate.

(Sources: Focusing on Wildlife)

Đăng nhận xét