Political divisions between industrialised and developing countries that surfaced at the 1972 Stockholm Conference have hampered much subsequent environmental cooperation.

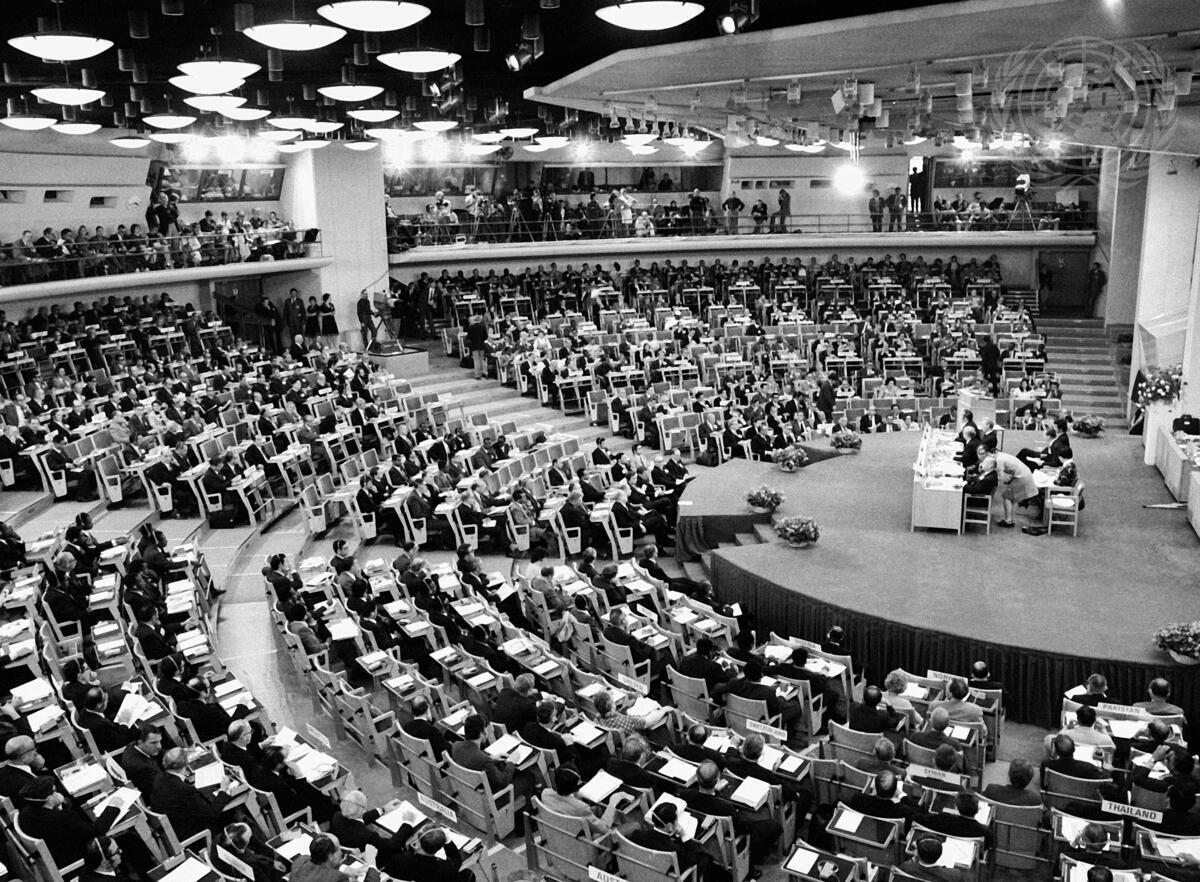

In June 1972, people from all over the world gathered in Stockholm, Sweden, for the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment – the first global conference on environmental issues.

It was an event heavily shaped by the geopolitics of the time, and would itself shape the geopolitics of the environment in the decades that followed.

At the time, clashes between the Soviet Union and the United States on a host of politically contentious issues were widening rifts between east and west. Sweden and other supporters of the conference thus hoped to use preparations for it to build bridges within a deeply fractured UN. Sweden viewed the Cold War from a position of political neutrality. It saw transboundary issues around environmental pollution as a potential area of cooperation and believed the environment was an appealing topic for a conference that could help boost the global importance of the UN.

However, even though the Soviet Union and the United States had supported the proposal during discussions in the UN General Assembly, the Geneva-based secretariat preparing the meeting often had to strike a delicate balance between east and west. In the end, disagreement around the participation of East Germany and West Germany – neither country a UN member state at the time – cast a shadow over the Stockholm Conference, resulting in a boycott by the Soviet Union and most members of the Eastern Bloc.

More significantly, over the long term the talks also served to heighten divisions between the developed and developing world. The conference was part of an important shift in north–south relations within the UN and other multilateral forums. During the UN General Assembly debates in 1968, many developing countries had expressed misgivings about plans for an environmental conference, believing it would be dominated by interests of wealthier, industrialised countries – arguments that are familiar today.

Developing countries of the global south argued that the world’s environmental problems were largely caused by the industrialised countries of the global north, and that related abatement costs should be borne by these countries. They believed environmental concerns should not be used as an excuse to impose development restrictions on countries already on the periphery of the global economic system; instead, they stated, the UN should focus on addressing poverty in their countries.

The UN General Assembly resolution in 1968, which called for the holding of a global environmental conference, specifically emphasised that the problems of the human environment were essential for sound economic and social development in developing and industrialised countries. During the conference preparations in June 1970, India and Nigeria welcomed cooperation on environmental issues, but underscored that their economic development must not be hindered.

Brazil went a step further to argue that some environmental degradation should be accepted as developing countries looked to grow their economies.

As an aspiring political leader among the world’s developing countries, the nation took on a particularly confrontational approach during UN General Assembly debates in November 1970, with Brazilian delegates particularly stressing the responsibility of western industrialised countries to take the lead in addressing environmental problems, both domestically and internationally. Brazil also insisted that industrialised countries should not introduce trade-restricting measures in the name of the environment, such as environmental requirements that would render goods more expensive. Brazil would not accept any formulation that infringed on national sovereignty, when discussing the need to inform other countries of environmental disasters. Its delegates also argued that the UN gave too much priority to new issues such as the environment, oceans and space, diverting attention away from the organisation’s core role of maintaining peace and supporting economic development.

As the preparatory work progressed, Brazil continued to demonstrate a desire to take on a leadership position among the world’s developing countries. This was, for example, reflected during the negotiations over the draft declaration for the Stockholm Conference when Brazil – at that time under a military dictatorship – successfully suggested the addition of two Mao Zedong quotes to a text proposed by the United States (which in turn built on an earlier Swedish proposal). Thus the second paragraph of the Stockholm Declaration includes a line from The Little Red Book: “Man has constantly to sum up experience and go on discovering, inventing, creating and advancing”. Elsewhere, in the fifth paragraph, there is a line from Mao’s 1936 work, Problems of Strategy in China’s Revolutionary War: “What is needed is an enthusiastic but calm state of mind and intense but orderly work.”

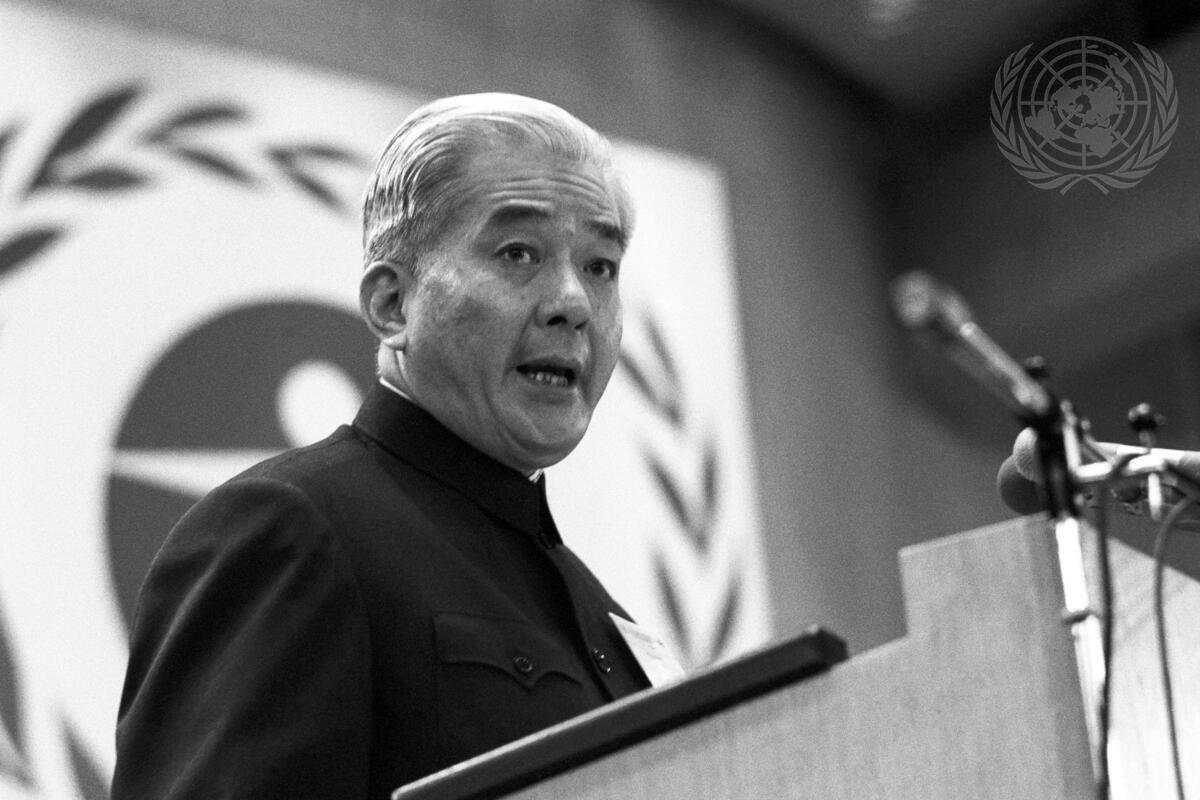

The Stockholm Conference was one of the first global political conferences attended by representatives from mainland China after the PRC took over the UN seat in 1971. A Chinese delegate gave a highly politicised speech at the Stockholm Conference, decrying capitalism and fiercely condemning the United States. However, China was not the only country criticising the US: Swedish prime minister Olof Palme also delivered a politically charged speech that was deeply critical of the Vietnam War, leading to tensions between Swedish and US officials during the meeting.

In the lead-up to Stockholm, some developing countries, including Iran and India, attempted to find common ground between industrialised and developing country positions around issues of environment and development. In an influential speech at the conference, Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi made a clear distinction between the pollution of affluence in the global north and the pollution of poverty in the global south. This related to ongoing debates about the relative contribution to global environmental degradation from population growth in developing countries (as often stressed by industrialised countries) and high consumption rates in wealthier countries (as raised by developing countries).

Beyond Stockholm

Only a year after the conference, World Bank economist Tim Campbell wrote that “Stockholm should be remembered more for its catalytic effect on political alliances than for its environmental or scientific contributions to the world.” Half a century later, we agree with Campbell’s early assessment, insofar as the preparations for, and holding of, the conference helped promote east–west cooperation around transboundary pollution issues, and moved developing countries to articulate a more common political agenda around environment and development issues.

It is also evident, however, that once all the delegates had departed Stockholm, many important characteristics of national sovereignty, territorial competition and the international political economy remained largely unchanged in international politics and cooperation.

The Soviet Union and the US continued to use international environmental issues as an area for expanded political cooperation and détente in the aftermath of the conference. Such cooperation, for example, helped pave the way for the adoption of the 1979 Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution, under the auspices of the UN Economic Commission for Europe. This convention has been an important instrument in addressing acid rain and other transboundary pollution issues in Eastern and Western Europe.

Developing country concerns of being on the periphery of the global economy formed a basis for strengthening cooperation among these countries within the UN system. The Stockholm Conference became an important meeting for strengthening south–south cooperation through the G77 and the UN Conference on Trade and Development, despite considerable political tensions and conflicts among some major developing countries.

Many north–south divisions around environment and development issues have proven remarkably durable since the Stockholm Conference, continuing over the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro, the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, and the 2012 UN Conference on Sustainable Development, again in Rio.

Such divisions have also been visible across many different areas of environmental treaty making, including climate change. The Stockholm Conference motto of “Only One Earth” encompassed a notion of all people being joint passengers on Spaceship Earth, but country-based delineations and the sovereignty principle have remained strong. During the preparations for the conference, many countries insisted national sovereignty must not be compromised by monitoring and other data-gathering systems on the amount of carbon dioxide and other pollutants in the atmosphere, as well as toxic substances in the oceans.

The 50th anniversary of the Stockholm Conference marks half a century of global cooperation on environment and development. The conference was instrumental in putting intersecting environment and development issues on the global political agenda. This has resulted in important related developments in international law and discourse.

Yet, many of the political divisions between industrialised and developing countries that surfaced at the conference have hampered much subsequent global environmental cooperation. In addition, wealthier and poorer countries all over the world maintain a strong focus on their territorial sovereignty related to domestic natural resource-use and economic and environmental policymaking. This, coupled with political and economic competition among countries, including over access to natural resources, continue to shape geopolitics in the 21st century.

Đăng nhận xét