Both Pakistan and India regularly forbid rice cultivation to conserve water and prevent land degradation. But with the crop tied to farmers’ livelihoods, a blanket ban is a weak solution

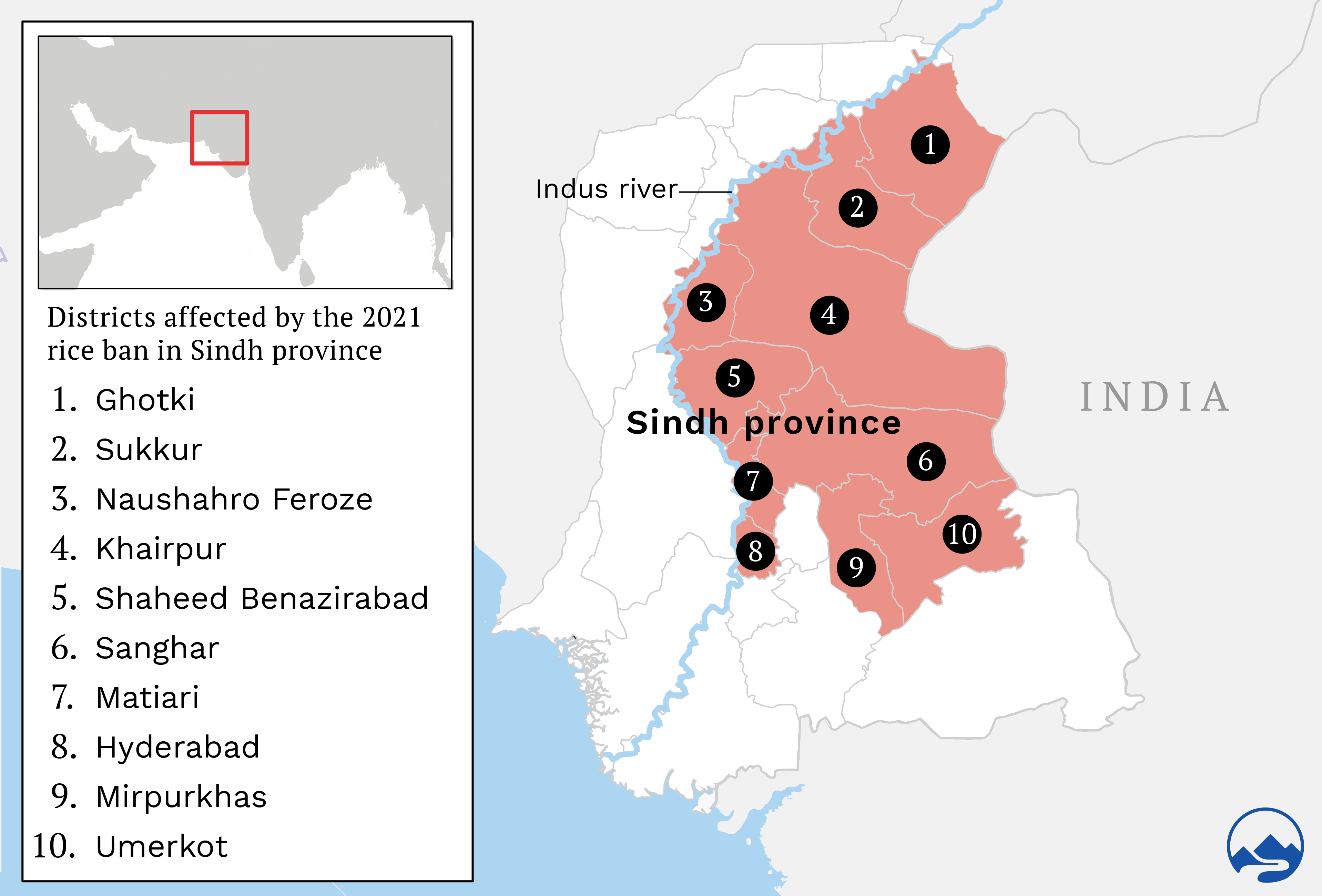

The season for sowing paddy is about to kick off in Sindh. But the province in southeast Pakistan has banned rice cultivation in 10 districts on the left bank of the Indus river.

This ban is announced every year at the end of April or early May to limit the waterlogging, salinity and drought-like conditions caused by successive rice farming. By some accounts, rice cultivation has been banned in these areas for over 90 years. Similarly, in India the government bans paddy cultivation in ‘dark zones’ to help water aquifers.

But these orders fall on deaf ears, as rice cultivation continues in large swathes of farmland in both countries.

Rasheed Channa, spokesperson for Sindh’s chief minister, said this time will be different. The government is “dead serious” about penalising those who violate the ban, Channa said. District administrations have already been told to be on the lookout for nurseries and “raze the seedlings before they can be transplanted” to flooded fields.

The news sparked considerable anger within the farming community, with farmers saying the government’s timing and thought process were poor.

“The growers were informed just a month before sowing that paddy will not be allowed. They had not prepared land or bought seeds to grow an alternative crop,” said Mahmood Nawaz Shah, senior vice-president of the Sindh Abadgar Board, an organisation formed to protect the rights of farmers in the province.

Policymakers must realise that switching crops on more than 40,000 hectares after the season for other crops has passed is “almost impossible”, he added.

“Even if 20,000 acres [8,000 hectares] are suddenly cultivated for other crops, where will we get buyers from? The prices of vegetables, pulses and fruits will fall,” he pointed out.

Rice and water

While fears for livelihoods are valid, the ban underscores the government’s growing concerns about water scarcity. The chief minister, who is a progressive farmer himself, said one kilogramme of rice requires up to 3,000 litres of water. Officials said water standing in rice farms for long periods of time has caused waterlogging, and that the high-delta crop also uses up other crops’ share of water for irrigation.

As Pakistan grapples with increased glacial melt and erratic rainfall, managing the canal-fed, water-intensive rice crop is yet another problem. The issue is exacerbated by high demand and the fact that rice generates 8% of Pakistan’s income from exports.

Zahid Bhurgri, general secretary of the Sindh Chamber of Agriculture, a lobbying group for famers, agrees that rice causes waterlogging and soil destruction. But he also said it is “safe”.

“It is considered a safer bet, especially as we confront climate change [because of which] too much or too little water can destroy other delicate crops, like cotton,” Bhurgri said. He added that rice is an easier crop to grow as it “requires nothing but to be submerged in three to four inches of water”.

Justifying the rice ban

“There will be 30% less water this year,” said Sindh’s agriculture minister, Ismail Rahu, to The Third Pole, justifying the ban on the “water guzzler”.

Though Rahu acknowledges that “rice is the bread and butter of hundreds of farmers”, he suggested they cultivate low-delta crops, such as beans, melon and vegetables, as they are less water-intensive and detrimental to the soil.

In many of these districts, the water that is available is of poor quality.

Zarif Khero, the chief engineer at Sindh’s Irrigation Department, said the most important consideration is soil fertility, which is spoilt by rice.

“The way [rice cultivation] is done by flooding the fields causes waterlogging, which will eventually turn the soil into wasteland,” he said.

Avoid bans, find alternatives

Rafique Suleman, a spokesperson for trade body the Rice Exporters Association of Pakistan, sees the ban as nothing short of an “atrocity”.

“Instead of providing incentives to grow more, the government is taking away our livelihood,” he said. He pointed out that rice, Pakistan’s second-biggest export after textiles, annually brings in around USD 2.5 billion into the country.

There is similar resistance in India. Despite depleting groundwater in paddy farming areas, farmers do not give up rice because of assured buying from the states of Punjab and neighbouring Haryana.

The only way out, some say, is to give farmers incentives to grow something else.

A farmer with an idea

This is where Asif Sharif, a progressive farmer from Pakpattan in Pakistan’s Punjab province, comes in. Sharif, an online sensation within the South Asian farming community, has a solution: if rice has to be grown, it should happen without flood irrigation. According to him, the rice plant uses 70% of its energy just to survive the inundation.

“Rice can be grown with minimal water,” said the 70-year-old. He added that the ban in parts of Sindh is “unnecessary”.

“Give it less water and the yield will be three to four times more,” he said, adding that the soil should be kept reasonably moist.

Sharif grows a variety of crops on his 200 hectares of land and has thousands of farmers listening to his every word. He engages with the virtual community and gives advice to people from across the globe.

He has more than 24,000 followers, mostly farmers, including quite a few from Indian Punjab. They share videos on his Facebook page, titled Pedaver, showing how well their crops are doing after they follow his tips.

Sharif said “everything can be grown anywhere”.

He advocates for farmers to return to doing cultivation on raised beds, without tilling and using organic mulch. Paradoxical agriculture, or paedar qudrati nizam kashtkari (PQNK) as he calls it, is a “comprehensive climate-smart production process total solution”.

“The PQNK process took several years to develop and mature,” said Sharif. “I started with the System of Rice Intensification in 2008. Then merged the crop system of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ Conservation Agriculture by 2011. This is how PQNK evolved by 2014.”

The results are impressive. “In Punjab, we have reduced the production cost of wheat from 1,500 Pakistani rupees (9.70 US dollars) to PKR 400 (USD 2.60) per 40 kg,” he claimed.

And yet, he has been unable to bring about a revolution. He faults the farm munshi or manager for thwarting development. “They get huge kickbacks by creating demand for each input that increases the cost of production,” he said.

Farmers with huge landholdings are also to blame, he said. “In connivance with corporations and businesses, they keep the rural population deprived of knowledge and therefore, prosperity,” he said.

He talked of the need for a “crop production management company” that travels to different farmlands, teaching farmers how to grow certified crops that are exportable.

Zarif Khero from Sindh’s Irrigation Department supported the idea of training. “Farmers should engage with students from agricultural universities so they can transition to modern methods of sustainable farming which can result in better yields,” he suggested.

Đăng nhận xét