Nian gao is a sticky cake for sticky situations.

DURING LUNAR NEW YEAR, A prosperous future belongs to those who eat their weight in luck. Diners slurp long noodles to ensure long lives and scarf down bone-in fish to swim to new fortunes. But the sweetest of these auspicious New Year dishes may be nian gao, a sticky cake eaten with the hope that the upcoming year will be more fortunate than the last.

Like many symbolic Chinese dishes, nian gao comes with its own set of origin stories about warding off bad luck and overcoming hardship. Lucas Sin is a Hong Kong native and the chef at Junzi,* which has locations in New York and Connecticut. He recalls hearing the nian gao legend as a kid growing up in Hong Kong. According to the story, a giant monster named Nian would appear during the winter to prey on a village. With its sharp teeth, jagged horns, dog-like body, and a hairdo resembling a barrister’s powdered wig, Nian routinely intimidated the villagers into hiding. The villagers lived in constant fear, until a particular family hatched a plan.

“There’s this one family with the name Gao that fought Nian off by feeding it [cake] and using firecrackers,” Sin says. Nian feasted on the dessert and returned to the mountains satiated, leaving the villagers at peace. “And so, we eat nian gao to celebrate the feeding of this monster.” As the legend goes, the name for the dessert comes from combining Nian, the monster’s name, with Gao, the heroic family.

Different versions of the Nian story exist, but this variation is widely accepted and most commonly portrayed in performances today. Lion dancers, sporting bright red-and-gold sequined costumes and giant masks, act out the story of Nian on Chinatown streets to the boisterous soundtrack of tanggu drums. Only upon hearing firecrackers and accepting nian gao through holes in their masks do the dancers flee the scene. To many, the performance and the cake preserve the story of defeating Nian, which has come to symbolize “overcoming the year.”

The first written stories that mention the monster Nian emerged in the early 20th century, but ferocious beasts similar to Nian have existed in Chinese mythology for millennia. Ellen Neskar, a professor of Chinese medieval history at Sarah Lawrence College, sees a potential predecessor to this legendary beast in a mythology compilation titled Classic of Mountains and Seas (known as Shan Hai Jin), from the fourth century BC. In the text, which describes more than 550 mountains, 300 seas, and their inhabitants, one beast bears resemblance to Nian: The mountain-dwelling monster is “shaped like a normal dog but with leopard’s markings,” with points on the sides of his head resembling horns. Similar to Nian, the human-eating beast is a threat to those living in the mountains.

Neskar also believes that Nian could have evolved from the plague gods, a group of deities who unleashed illnesses into the world in response to human sin. Like Nian, plague gods could only be placated with prayers and food offerings. “The Nian monster is related to a lot of plague deities or demons that ultimately over time get transformed into gods of wealth,” she says.

Even with evidence pointing to Nian’s predecessors, there’s also a possibility that the monster was merely fabricated to carry on Lunar New Year traditions. In Mandarin, nian translates to “year” and gao translates to “cake.” Storytellers, eager to weave clever puns into their narratives, may have co-opted the term for cake as the legendary family’s name and, likewise, nian for the monster. As it turns out, this is a real possibility since customs relating to similar celebratory cakes predate Nian’s story.

The first customs related to cakes like nian gao were recorded during the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD). In Chinese New Year: Fact & Folklore, William C. Hu notes that gao, or pudding cakes, were originally “eaten not on New Year’s, but rather on the ninth day of the ninth lunar month,” on a holiday known as Chongyang. During Chongyang, Chinese people practiced denggao, a ritual that involved eating pudding cakes for good luck. As people started consuming more and more gao year round, the gao variation specific to Lunar New Year emerged as a favorite.

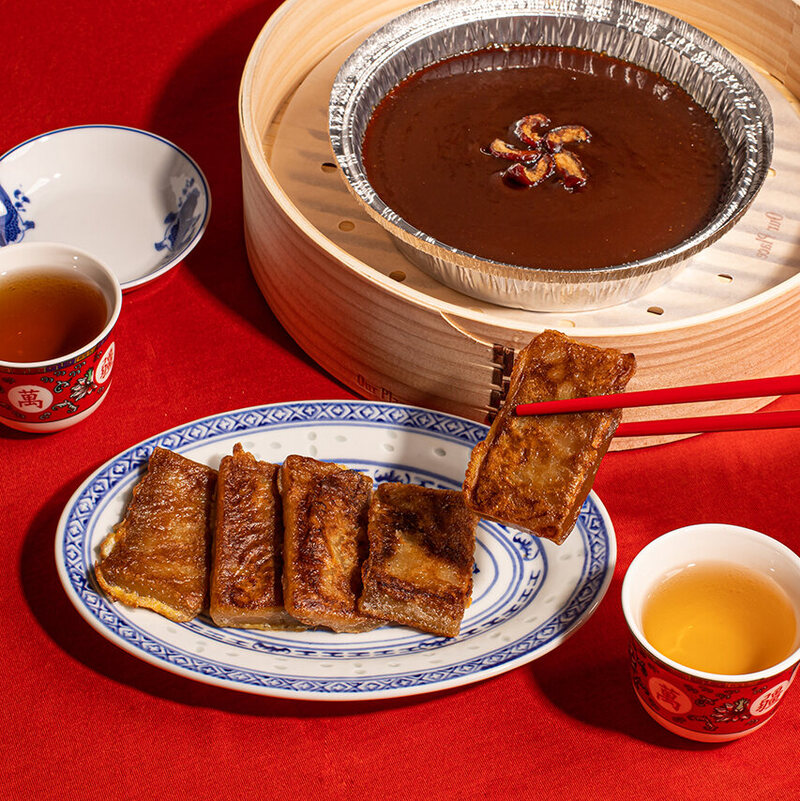

For such a popular and powerful dish, the cake requires only three ingredients: glutinous rice flour, brown sugar, and water. But it’s not as easy as it sounds: The sticky texture can be unwieldy and unpredictable. Teresa Cheng is the pastry chef at Mister Jiu’s in San Francisco, California. The last time she cooked nian gao in her home kitchen, she diced the dessert intending to pan-fry it, but instead the amorphous blobs clung to her hands and utensils. “It was so dense and sticky. We literally could not figure out how to cut it. And it was just a total mess,” she says.

Nian gao’s hallmark stickiness may trouble even the most skilled chefs, but like the cake’s monster-repelling powers, its very stickiness is said to have supernatural sway. At the start of Lunar New Year, many families burn a poster of the Kitchen God (also known as Zao Shen or the Stove God) that they’ve been keeping over their stove for the past year. This act sends the Kitchen God to Heaven, where he will inform the Jade Emperor of his host family’s behavior. Rather than leave their punishment or reward up to fate, Chinese families may meddle with the Kitchen God’s report by rubbing something sweet and sticky on the poster’s lips, a tradition recorded in poems dating back as early as the 10th century. As an additional layer of protection, some families now leave nian gao in front of the poster, a gesture meant to seal the Kitchen God’s lips shut in the event of a bad report.

Although Lucas Sin heard these legends countless times while growing up, he remains skeptical. “I didn’t grow up in a household where we, you know, genuinely believe these things,” he says. But for Sin and many others, nian gao represents something beyond luck and prosperity. Dishes like nian gao stick around because they also help reinforce the practice of giving in Chinese culture. Growing up in Hong Kong, Sin received coupons from friends and family to redeem nian gao at a local pastry shop. And as soon as Sin woke up each morning during the Lunar New Year, his father steamed, pan-fried, and plated nian gao as their first meal.

Even the gods and mythical creatures take part in the culture of giving and receiving during the new year. “The gods are really made in the image of humans. That’s why you give them things like sweet candies and nian gao, and that’s why you sacrifice food,” Neskar says. “They want what we want. They want good food, a good home, and nice clothing. And they make their demands really well-known.”

Whether it’s in the hopes of pleasing the Kitchen God or savoring the cake’s chewy texture, you can learn how to prepare nian gao with the three-ingredient recipe below.

Nian Gao (Sticky Rice Cake)

Yield: 6 slices

Prep Time: 1 hour

2 ½ sticks of Chinese brown sugar (or 1 cup dark brown sugar)

1 cup water

1 cup glutinous rice flour

2 Jujube dates or dried dates (optional)

1. Combine the brown sugar and water in a small pot, and heat on medium until the sugar dissolves. Set aside the mixture until it is warm, not hot.

2. In a medium bowl with the glutinous rice flour, slowly add in the brown sugar mixture. Whisk the flour into the sugar water until the texture is smooth. Then, pour the mixture into a 6-inch tin foil pan or equivalent. Garnish the top with sliced dates.

3. Place the pan in a steamer and let it steam for 30 minutes. Make sure the steamer lid is tight so that no heat escapes. You may need to add more water to the steamer if it boils away.

4. Let the nian gao cool to a warm temperature. You can serve the cake as is. Or you can cut the cake into strips and lightly pan-fry with oil on both sides, or dip the slices in an egg mixture and pan-fry.

* Correction: This article originally stated Lucas Sin was the chef and owner at Junzi. He is the chef.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

(Sources: Atlas Obscura)

Đăng nhận xét